Although NASA’s Kepler space telescope ran out of fuel and ended its mission in 2018, citizen scientists have used its data to discover an exoplanet 226 light-years away in the Taurus constellation.

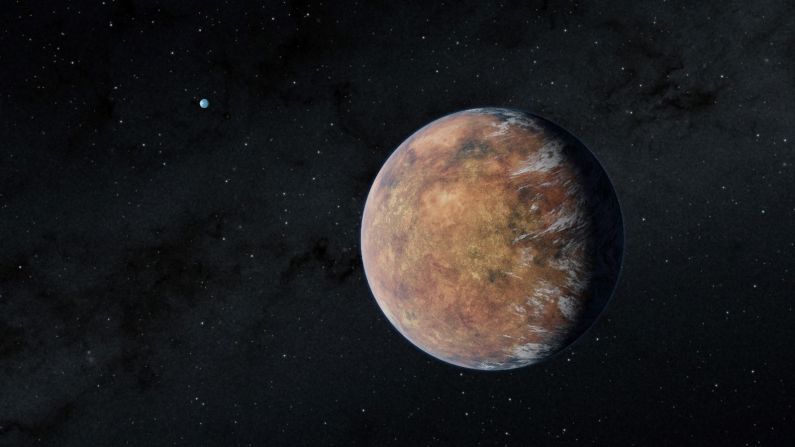

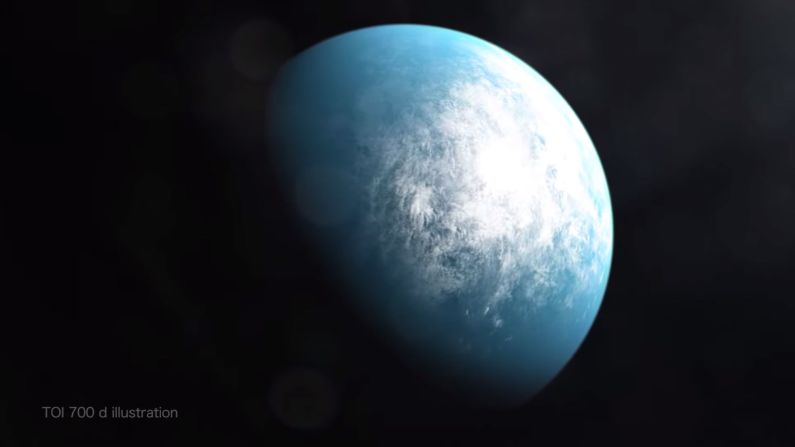

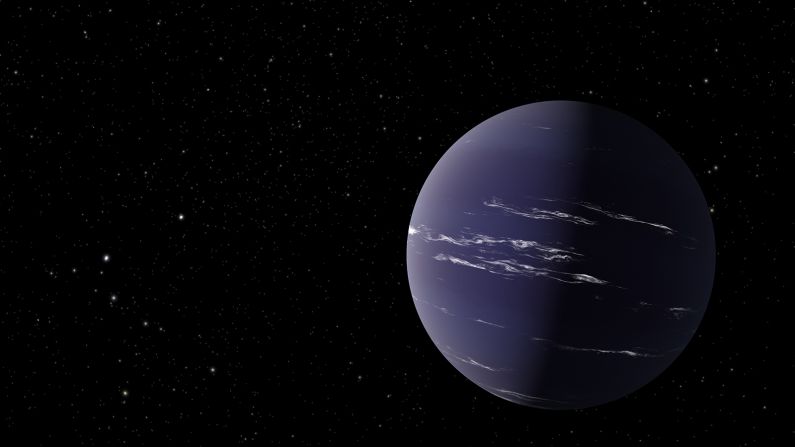

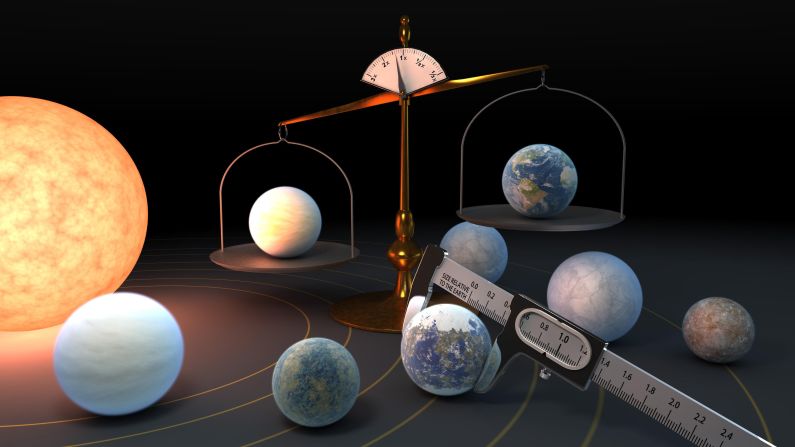

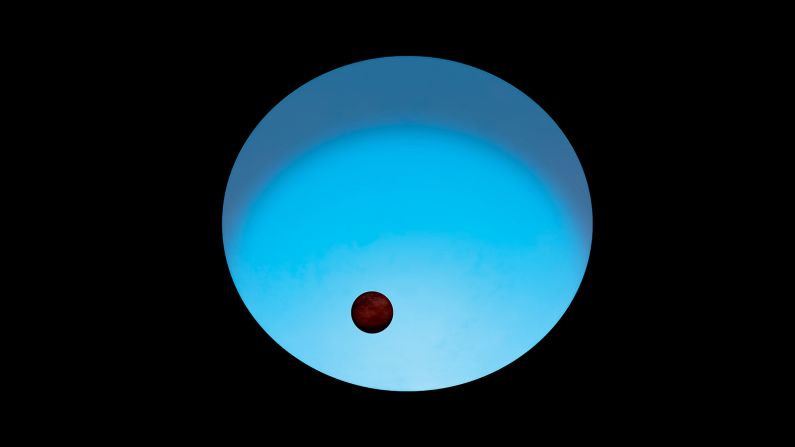

The exoplanet, known as K2-288Bb, is about twice the size of Earth and orbits within the habitable zone of its star, meaning liquid water may exist on its surface. It’s difficult to tell whether the planet is rocky like Earth or a gas giant like Neptune.

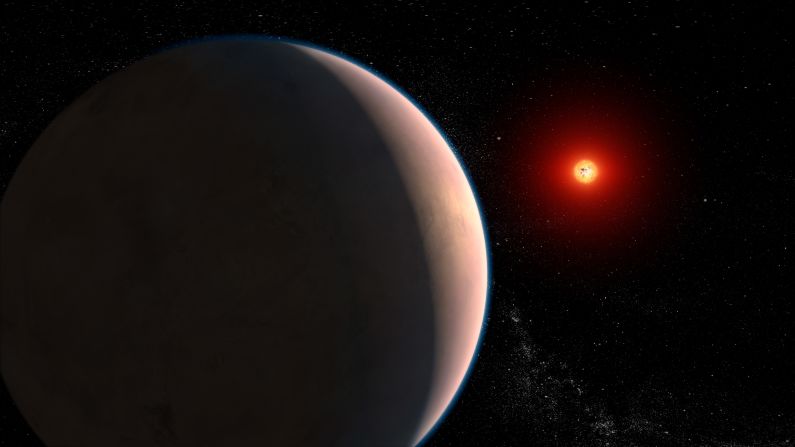

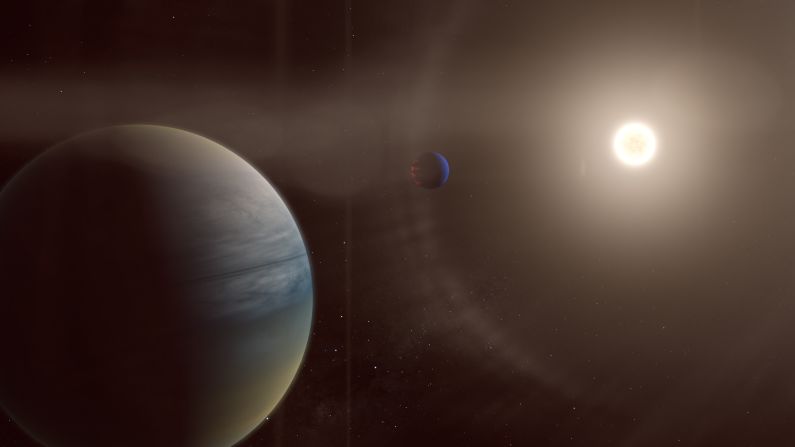

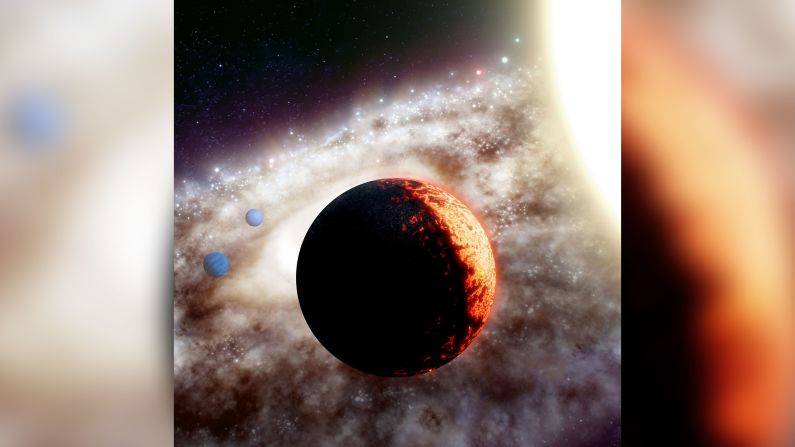

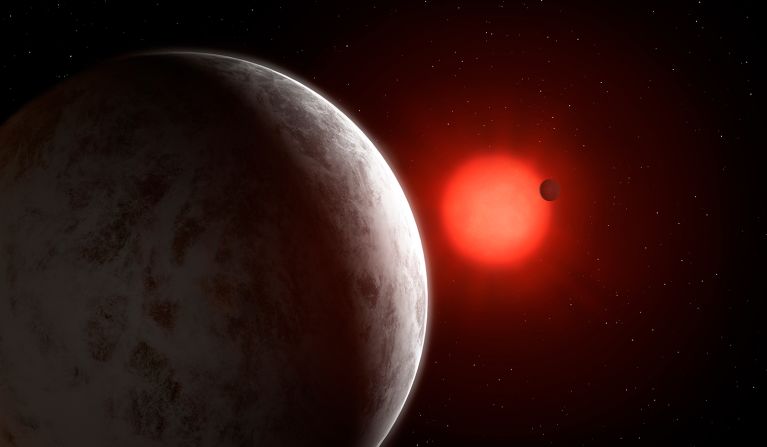

The planet is in the K2-288 system, which contains a pair of dim, cool M-type stars that are 5.1 billion miles apart, about six times the distance between Saturn and the sun. The brightest of the two stars is half as massive as our sun, and the other star is one-third of the sun’s mass. K2-288Bb orbits the smaller, dimmer star, completing a full orbit every 31.3 days.

K2-288Bb is half the size of Neptune or 1.9 times the size of Earth, placing it in the “Fulton gap”between 1.5 and two times the size of Earth. This is a rare size of exoplanet that makes it perfect for studying planetary evolution because so few have been found.

The discovery was announced Monday at the 233rd meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Seattle.

“It’s a very exciting discovery due to how it was found, its temperate orbit and because planets of this size seem to be relatively uncommon,” said Adina Feinstein, a University of Chicago graduate student in astrophysics and lead author of a paper describing the new planet that was accepted for publication by The Astronomical Journal.

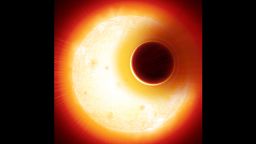

Although all of the data from the Kepler mission was run through an algorithm to determine potential planet candidates, visual manpower was needed to actually look at the possible planet transits – or dip in light when a planet passes in front of its star – in the light curve data. Kepler observed other events that could be mistaken for planet transits by a computer.

But the “reboot” of the Kepler mission in 2014 that led to the K2 mission allowed for multiple observation campaigns that brought in even more data. Every three months, Kepler would stare at a differentpatch of sky.

“Reorienting Kepler relative to the Sun caused miniscule changes in the shape of the telescope and the temperature of the electronics, which inevitably affected Kepler’s sensitive measurements in the first days of each campaign,” said study co-author Geert Barentsen, an astrophysicist at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in a statement.

Those first three days of data were ignored, and errors were corrected in the rest of the data gathered.

But the scientists couldn’t do it alone. There were too many light curves to study on their own.

So the reprocessed, “cleaned-up” light curves were uploaded through the Exoplanet Explorers project on online platform Zooniverse, and the public was invited to “go forth and find us planets,” Feinstein said.

In May 2017, citizen scientists began discussing a particular planet candidate, but it had only two transits, or passes of the planet in front of its star. The scientists needed at least three to mark it as an interesting target.

Feinstein and Makennah Bristow, an undergraduate student at the University of North Carolina Asheville, worked as interns at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, searching the data for transits. They had noticed the same system and its two transits.

But the citizen scientists found the third transit hiding in those first few days of data that had been all but forgotten.

“That’s how we missed it – and it took the keen eyes of citizen scientists to make this extremely valuable find and point us to it,” Feinstein said.

Follow-up observations were made with multiple telescopes to confirm the exoplanet.

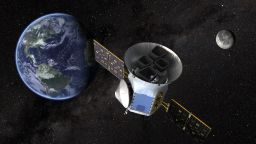

There will be more opportunities for citizen scientists to help discover exoplanets. NASA’s latest planet-hunting mission, TESS, will be providing more light curves that are full of potential planets waiting to be found.

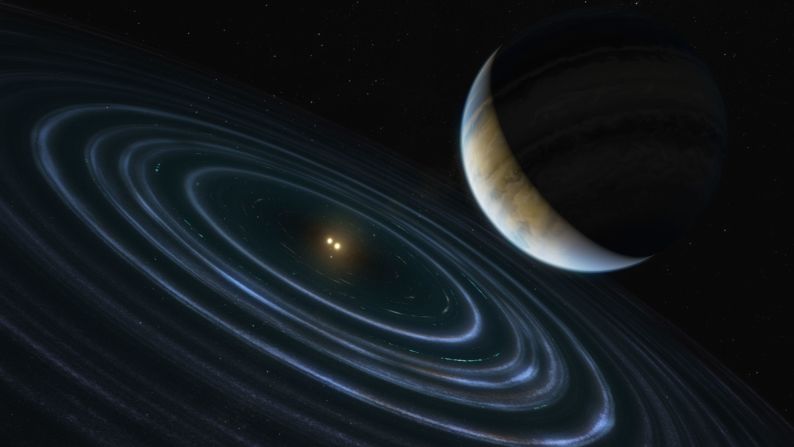

Last year at the American Astronomical Society meeting, it was announced that citizen scientists helped discover five planets between the size of Earth and Neptune around star K2-138, the first multiplanet system found through crowdsourcing.

This year, Kevin Hardegree-Ullman, postdoctoral scholar in astronomy at the California Institute of Technology, announced that the Spitzer space telescope followed up on that discovery and discovered a sixth planet, K2-138 g, smaller than Neptune, that orbits the star every 42 days.

“This is only the ninth system discovered containing six or more planets,” he said.