Kenya is the latest country where China is frantically defusing a public relations storm over President Xi Jinping’s signature Belt and Road megaproject.

In a statement Friday, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs dismissed as “not true” numerous reports that a key port in Mombasa was at risk of being seized by Beijing over unpaid debts.

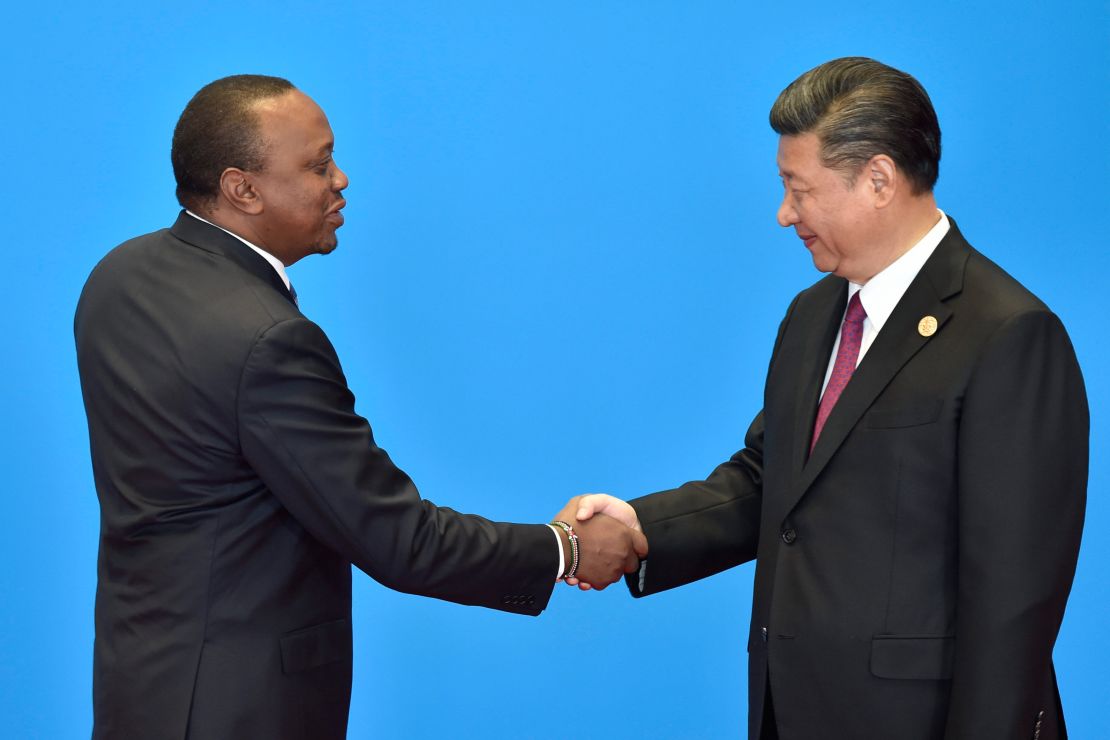

Speaking to journalists last week, Kenyan President Uhuru Kenyatta also pushed back, dismissing as “pure propaganda” reports based on a leaked letter from the country’s Auditor General warning that assets belonging to the Kenya Port Authority – including Mombasa’s massive Kilindini Harbor, the largest port in East Africa – were listed as collateral for a multi-billion-dollar loan to fund a railway project.

“The Chinese government themselves say this (it) is nonsense,” Kenyatta said, while the AG’s office denied publishing any such letter, copies of which circulated widely online.

Despite Beijing and Nairobi’s vehement denials, concerns over the loans speak to a growing fear in many developing countries that their governments, in rushing to cash in on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), have left themselves overextended, with Chinese state-owned companies ready to snap up ports, railways and other key infrastructure across the globe should debtors default.

Five years into the BRI, the sheen is also coming off the project in Beijing, amid an ongoing – though temporarily paused – trade war with the US, and concerns over future funding and returns on an increasingly unwieldy list of overseas investments.

Debt fears

For critics of the BRI, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota port is the perfect example of the risks developing countries are taking on with their Chinese loans.

In December 2017, Beijing acquired a 99-year lease to the port – located in a key strategic position on the Indian Ocean – in return for forgiving some of the billions of dollars the South Asian country owed China.

The move sparked fears China would use similar defaults in other countries to acquire a host of new infrastructure, with both potential economic and military benefits – leapfrogging rivals in the region such as India and the US.

In mid-2018, the Zambian government had to deny reports it was preparing to hand over control of multiple public assets, including the state broadcaster and Lusaka’s Kenneth Kaunda International Airport, to China.

Kenya’s own issues date to 2014, when Nairobi signed a multi-billion-dollar deal with the state-owned China Road and Bridge Corporation to fund a new rail link between the Kenyan capital and Mombasa, on the Indian Ocean.

The train line, known in Kenya as the standard gauge railway (SGR) project, was completed in 2017, slashing the transport time between the country’s two largest cities. It is now in its second phase, with the Kenyan government reportedly borrowing a further $1.6 billion from China to fund a line from Nairobi to Naivasha.

But while the SGR has been a boon to residents of Nairobi and Mombasa, it has yet to generate half the revenues anticipated in feasibility studies, according to The East African newspaper – raising fears over the country’s ability to repay the loan. It has also been criticized for being vastly overpriced, reportedly costing about three times the international standard.

Repayments are due to start in mid-2019, when a five-year grace period expires. On Friday, Kenyatta insisted that “we are ahead of our payment schedule.”

“We are not tied to any country,” he added.

‘Land grab’

In the first half of 2018, Chinese companies provided overseas loans of about $50 billion, according to the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), adding to the more than $8 trillion of investment previously announced.

However, that figure was down on the same period the year before as concerns grew over the BRI both overseas and back in China.

“(Late 2018) saw a number of high-profile projects suspended (including in Malaysia) or scaled back (including in Myanmar) amid growing concerns over debt sustainability and transparency,” the EIU report said.

Many countries that were initially willing to take Beijing’s money have expressed concern over what could happen should they default on debt payments, particularly after the Sri Lanka deal.

Part of the problem stems from Beijing’s “ad hoc approach” to settling debt issues, according to a report by the Center for Global Development (CDG), which pointed to a lack of consistency in dealing with defaulting nations. In the past, China has been willing to write off or restructure debts and extend further lines of credit, while at other times it has demanded assets to service the loans.

“Without a guiding multilateral or other framework to define China’s approach to debt sustainability problems, we only have anecdotal evidence of ad hoc actions taken by China as the basis for characterizing the country’s policy approach,” the CDG report said.

This creates significant uncertainty, and forces governments borrowing from China to rely on maintaining strong bilateral ties above all else to ensure future lending policies.

African leaders heaped praise on President Xi after the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC) in Beijing in September, with Botswana President Mokgweetsi Masisi telling state media “we admire and hold you in very high regard! Keep the innovation, friendliness and international outlook as bright as the Chinese spirit!”

“Your friends in Botswana wish the very best for a successful One China!” he added, an apparent reference to Beijing’s policy regarding Taiwan, a key element in its approach to Africa, where numerous countries have dropped diplomatic ties with Taipei in favor of Beijing in recent years.

Elsewhere, however, concerns and uncertainty over the BRI have sparked a backlash against China – particularly in the Maldives and Malaysia, where opposition parties critical of Beijing have recently taken power.

In January 2018, former Maldives President Mohamed Nasheed accused Beijing of staging a “land grab” in his country. After his Maldivian Democratic Party took power this November, it pledged to end “China’s colonialism” and renegotiate loans agreed by former strongman Abdulla Yameen with Beijing.

In August, recently elected Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad shelved two Chinese-funded projects over fears they could “bankrupt” the country.

China has vigorously pushed back against such criticism, saying it is subjected to a double standard.

“It is unreasonable that money coming out of Western countries is praised as good and sweet, while coming out of China it’s sinister and a trap,” Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Hua Chunying said in September.

Fork in the road

While the loudest criticism of the Belt and Road Initiative has come from overseas, there are also growing doubts over the project within China.

Since the BRI was launched, critics have warned the scheme could leave China overextended, with billions of dollars wasted on projects that never pay off. While Beijing may acquire control of certain projects in return for forgiving debts, any strategic wins could be outweighed by a host of white elephant investments that offer little benefit to China.

A recent survey conducting by Peking University and the Beijing-based Taihe Insitute found that nearly half of 100 countries evaluated were not a good fit for BRI projects due to weaknesses in financing and infrastructure, adding that the government should “assess and prevent the risks” before pushing ahead with them.

The BRI is also facing pressure from Washington – despite the temporarily paused trade war – and other rival nations keen to restrain China from supplanting their influence over developing countries, as well as a potential funding shortfall for future projects.

While boosters for the BRI remain plentiful, and the project is not on the verge of failing any time soon, there are signs that a shift is underway. The number of contracts signed in 2018 was down on previous years, and country’s big development banks have reportedly been told to partner with the World Bank and other international lenders on future projects.

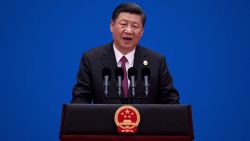

The Belt and Road Initiative was supposed to be Xi’s signature project, one that would drive China back to its traditional position of power and dominance both in Asia and wider afield.

But as the country enters 2019, the plan is looking shakier than in ever – and appears in need of a rethink. Failure to do so, according to Bloomberg analyst Nisid Hajari, risks that “this plan to project Chinese power, influence and trade across much of the world could undermine all three.”