By the time Lynn D. turned 2, he had already undergone seven surgeries. His childhood memories – in the German states of Bavaria and Hesse – were shaped by monthly visits to the doctor, where he says up to 50 researchers would observe examinations of his naked body.

When he reached puberty, Lynn was given growth blockers and high doses of hormones; as a teenager, he started self-harming, developed post-traumatic stress disorder and became suicidal.

Lynn, 34 – who has asked CNN to identify him by his preferred name – was born with both male and female sex organs. His doctors and parents decided shortly after he was born that his sex would be female, so his penis and testicles were surgically removed. His ovaries were also removed.

Doctors had told Lynn’s parents the surgeries were preventative, citing concerns that he could develop cancer, but Lynn says there was no medical reason for him to be operated on and that the surgeries were carried out with a “dubious motivation.”

“The doctors advised my parents not to tell me about my sex and simply raise me as a girl,” Lynn told CNN. “And of course, it didn’t work – because I’m not a girl.”

Lynn is intersex, an umbrella term used to describe a variety of conditions in which a person is born with reproductive or sexual anatomy that does not fit into binary definitions of female or male.

“I was labeled a girl; I wanted to be a girl and fit in – but it did not work. I got along better with boys so I thought, ‘I’m a boy’. But then I realized that I’m not a boy either … boys also started to marginalize me. I did not have a good connection with my body and nobody helped me to establish a good connection with my body,” Lynn said.

Lynn only learned that he was intersex during a therapy session at the age of 20. It was a revelation for Lynn, who had struggled to fit in with his peers for so many years.

While it helped him to move forward with his relationship with his own body, Lynn says it damaged his relationship with his parents.

“My body was changed so much to fit in – whether it happened consciously or unconsciously. The whole experience broke my relationship with my parents. We still have not gotten over this yet,” Lynn said.

When he first learned he was intersex, Lynn said, “it felt like as if someone said I am an alien, you are from someplace else. You are a mutant.”

“It took me a while to come to terms with my diagnosis and for me to (come to) grips with it. But then I understood – everything made sense to me. I no longer felt restless. Suddenly I understood who I was.”

More than a decade later, Lynn said he has evolved into an “enormously happy” person, someone who is in a loving relationship with a woman, and who is fulfilled by a career in engineering and gigging in a punk band.

While Lynn said he accepts being called “him” for now,he wishes that there was a specific German pronoun to describe intersex people, and hopes that society will one day understand what it means to live outside of binary definitions of sex and gender – and to accept intersex people for who they are.

A change to the German constitution could be the first step toward that recognition.

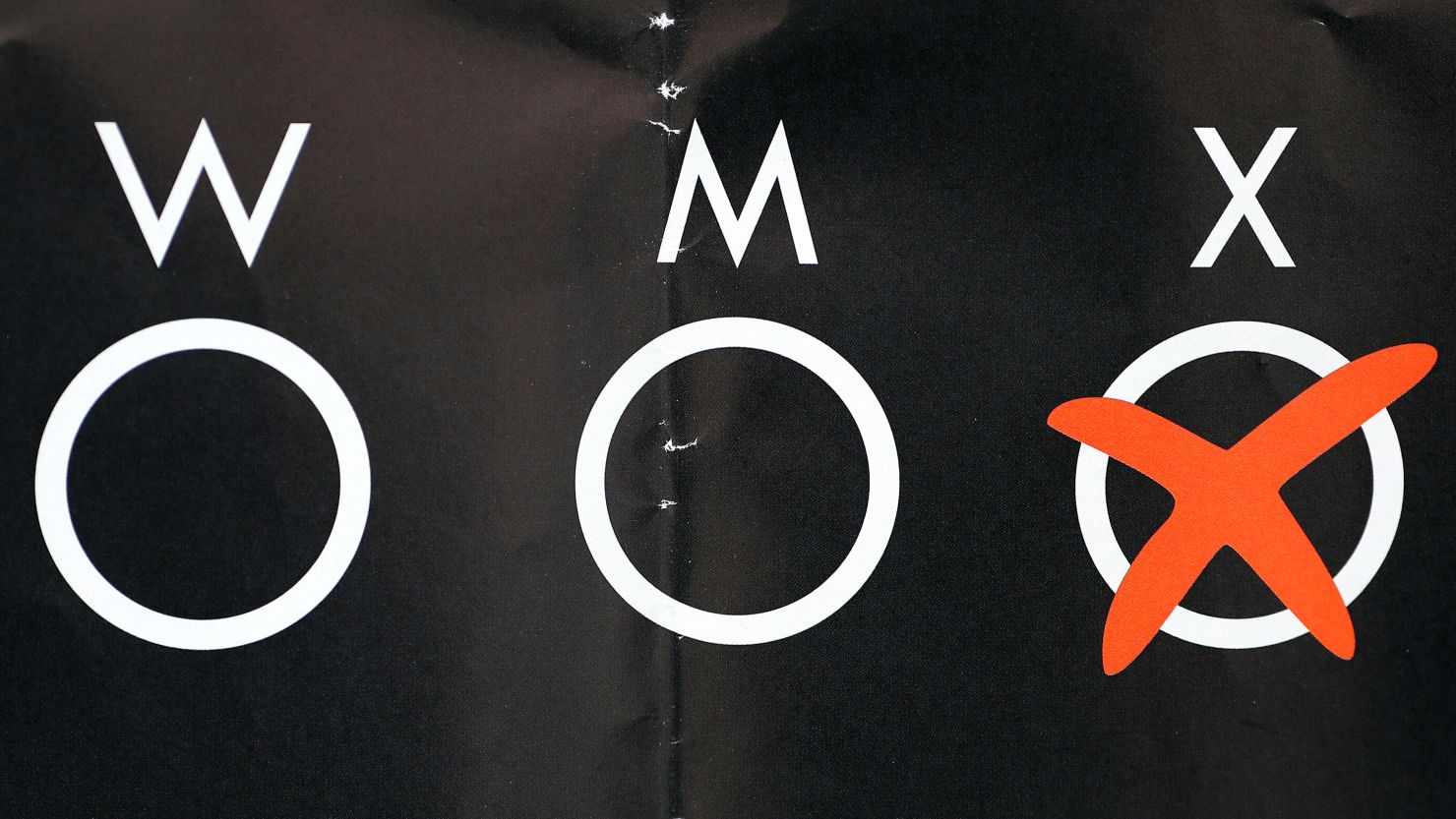

On January 1, Germany will become the first country in the European Union to offer a “third gender” option on birth certificates.

Intersex people – and parents of intersex babies – will be able to register as “divers,” or miscellaneous, on birth certificates, instead of having to choose between male or female.

The law, passed in Germany’s Bundestag earlier this month, was hailed as a “small revolution” by some intersex activists. It came after the 2017 constitutional court ruling in favor of an intersex person’s right to change their birth certificate from female to “divers.”

The court ruled that Vanja – an intersex person who goes by a one-name pseudonym and uses the gender-neutral pronouns “they” and “them” – had their “right to positive gender recognition” violated and found that the current law was unconstitutional.

Vanja, whose case was supported by advocacy group, “Dritte Option” or, the Third Option, told CNN that having to decide between being a woman or a man on official documents left them feeling “left out and overlooked.”

While Vanja’s official identification documents said they were female, this led to “a lot of irritations with people” because they presented – or physically appeared in society – as male.

Vanja initially considered changing their documents to male, but eventually decided that decision would devalue their identity, which is intersex.

“I thought to myself, if I am going at lengths to change something within the red tape system in Germany, I want to have something that suits me,” they said.

Vanja plans to celebrate the new law by changing their birth certificate category to “divers” in the new year, calling it both a personal and a practical step.

“I asked myself so many times what it means to be intersex; I often was upset when I had to decide which box to tick – male or female. I felt (like I was) being pushed into the corner, that I had to adjust non-voluntarily. I think it will give me a new feeling of peace,” Vanja said, adding that they hope other countries in Europe will follow suit.

But, like many in the intersex community, Vanja believes the law is just a stepping stone.

“Societal acceptance cannot be mandated by a court ruling, but it is a step in the right direction,” Vanja said.

Lynn agrees. While he also plans to register as intersex – and to officially change his name to Lynn – he said there are still many steps that need to be taken for intersex people to be “fully integrated into society.”

Still, he is hopeful the new law will help to bring attention to the medical treatment of intersex people and open conversations for change.

‘Ritualized, sexualized violence’

Infants born with visible variations in their sexual characteristics, like Lynn, often undergo painful and irreversible surgery to give them the appearance of a conventional male or female gender, according to an Amnesty International report published last year.

The surgeries stem from a theory popularized in the United States in the 1960s by the psychologist John Money, who believed that an intersex person’s make-up was a product of abnormal processes. Money believed that intersex people ought to become either male or female and as a result, were in need of medical treatment.

Although that theory is no longer widely accepted in the medical community, its “echoes can still be found within the medical establishment today,” according to the Amnesty report, citing interviews with medical professionals across Denmark, Germany and the UK.

Those surgeries stripped Lynn of his bodily autonomy and left him with painful scars.

“When they (doctors and parents) talked about my body, I had to go out and leave the room. In hindsight, it was a practice I would now compare with a ritualized, sexualized violence. It was massively traumatizing,” Lynn says of his childhood visits to the doctor.

READ: Shame, taboo, ignorance: Growing up intersex

A group of United Nations and international human rights experts called for “an urgent end to human rights violations against intersex children and adults” in 2016, calling on governments to ban harmful medical practices and protect intersex people from discrimination.

Between 0.5% and 1.7% of the global population are born with intersex traits, and are at risk of human rights violations that include surgery, discrimination and torture, according to the UN.

In July, a group of European medical experts published a set of new guidelines that urge doctors to defer medically unnecessary surgeries on intersex children until they are old enough to consent. The European consensus said: “For sensitive and/or irreversible procedures, such as genital surgery, we advise that the intervention be postponed until the individual is old enough to be actively involved in the decision whenever possible.”

Grietje Baars, a senior lecturer at The City Law School in London, told CNN that while the new law demonstrates a “greater recognition of life beyond the binary,” the “third gender” option doesn’t go far enough to fully recognize gender diversity.

Under the new law, people wanting to change their birth certificate to read “divers” will only be able to do so with a medical certificate to prove it.

Baars – who also goes by the gender-neutral pronouns, “they” and “them” – says that requirement could subject intersex people, who often have a history of “traumatic medical interference with their genitalia” to additional trauma. Plus, Baars says, the medical requirement reinforces an antiquated definition of gender based solely on biology.

“You can not simply decide gender by looking at people’s genitalia,” they said, adding that it might be time to remove gender from official documents altogether. While Baars understands that this might sound radical, they argue that “abolishing gender registration does not mean abolishing gender as such.”

“It’s like abolishing registering your religion or race on your ID or documents – it does not mean you can no longer be Catholic or black … those things are not the same. I am just saying that it is no business of the state to register and categorize people in that manner,” they said.

Challenging social norms

Although German law has allowed parents to leave the gender box blank on birth certificates since 2013 – and this will still be an option under the new legislation – some experts say parents will still be inclined to choose a more traditional approach, noting that in the two years after the blank box option came into effect, only 12 children were registered without a sex marker in the birth registry.

Anike Krämer, a Ph.D. candidate in gender studies at Germany’s Ruhr-University Bochum, told CNN that she believes that parents of intersex children will have “difficulties” with the choices presented with the new law.

“The structure we have right now simply does not allow for parents to embrace this new law. The medical advice is still very conservative and advises to go with the binary system,” Krämer said.

Under German law, parents can not generally consent to “feminizing,” “masculinizing” or “disambiguation” surgeries, unless it is deemed medically necessary or life threatening, according to the German Inter-ministerial Working Group, IMAG.

However, the law currently does not ban these surgeries for children too young to consent, and leaves the often ambiguous question of what is deemed surgically necessary up to medical professionals who might continue to characterize intersex people’s bodily traits as disorders.

Krämer says that parents are more concerned with the every day questions their children will face in society: “How do I call my child; which pronoun should I use, what do I tell my neighbor, how do I educate my intersex child?

“Sociologically speaking, parents lack options for action. Apart from medical consultations they often lack alternatives. If there are true alternatives in place – to address the parents’ questions, fears, difficulties and options, to speak with other intersex individuals or other parents of intersex individuals – then that would make it easier for parents to perhaps choose the third option at the registry entry.”

Get CNN Health's weekly newsletter

Sign up here to get The Results Are In with Dr. Sanjay Gupta every Tuesday from the CNN Health team.

“But Germany is not that far yet,” Krämer said, adding that the law’s medical requirements“misses a chance to create a wider law for more people,” and sidelines other individuals who are not intersex but do not identify as only male or female, such as members of the trans community.

And she is not alone.

Markus Ulrich, spokesman for the Lesbian and Gay Federation in Germany, told CNN that the law “does not go far enough to protect people of non-binary identities.”

Ulrich said that while the law was “a huge step forward in acknowledging more rights and … visibility for people beyond ‘man and woman,’” the government effectively ignored an alternative option proposed by the constitutional court last year to abolish gender registration all together – a more inclusive option for people whose birth sex doesn’t fit their gender identity.

A handful of German politicians, including members of the Green Party and the Social Democratic Party, have also criticized the law’s medical certificate stipulation, pointing to other countries that allow people who don’t identify in binary terms to change their official documents to match their gender identity.

In 2014, the Australian High Court ruled that the government should legally recognize a third gender. And in 2017, California became the second US state (after New York) to allow residents who don’t identify as male or female to change their birth certificates to match their gender identity.

Several other countries have provided gender-neutral options on passports and official documents such as the census or ID cards, including Argentina, Bangladesh, Canada, Denmark, India, Malta, Nepal, the Netherlands, New Zealand and Pakistan.

While intersex, trans and other human rights advocates continue to call for Germany’s new law to be made more inclusive, Lynn hopes that at least this first step will help society to understand intersex people better – and to not be afraid.

“We are all normal people and want to live our lives like others,” he said.