As people were ringing in the new year on Earth, NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft conducted a flyby of Ultima Thule, a Kuiper Belt object more than 4 billion miles away.

Or so we hope. We won’t actually know until a “phone-home call” signal is established Tuesday morning around 10 a.m. ET. But mission scientists celebrated the countdown to 12:33 a.m. ET at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory.

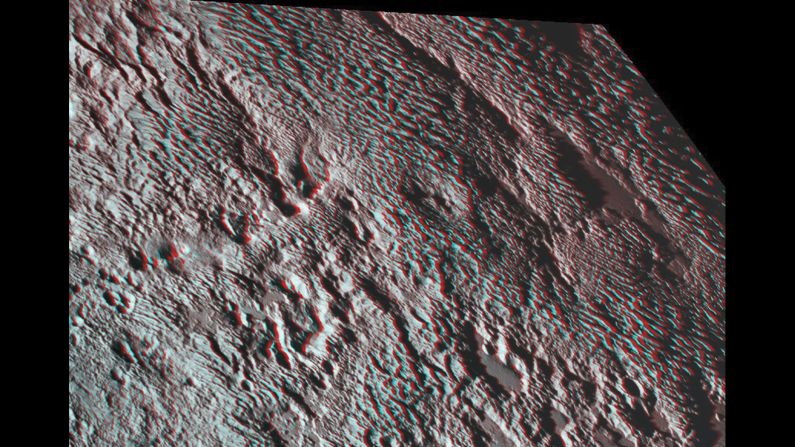

Brian May, Queen guitarist and astrophysicist, is also a participating scientist in the New Horizons mission. He’s particularly interested in stereo imaging for this leg of the mission. But he was also inspired to release a new song celebrating New Horizons on New Year’s Day.

“This mission represents to me the spirit of adventure, discovery and inquiry which is inherent in the human spirit,” May said during the countdown to the flyby. He wrote a new song to honor the mission called “New Horizons (Ultima Thule Mix).”

So what is Ultima Thule?

The object is so old and pristine that it’s essentially like going back in time to the beginning of our solar system.

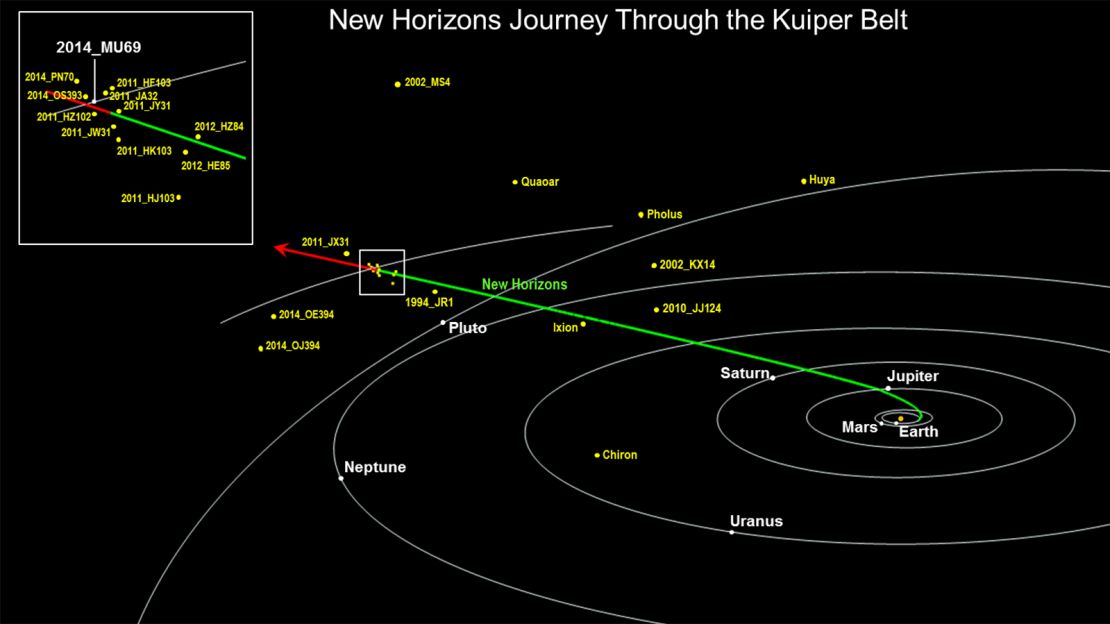

This flyby is the first exploration of a small Kuiper Belt object up close – and the most primitive world ever observed by a spacecraft. Ultima Thule orbits a billion miles beyond Pluto and is probably a bit of a time capsule from the early solar system.

New Horizons is moving through space at 31,500 miles per hour, and it has one chance to get it right as it zips past the object.

The Kuiper Belt is the edge of our solar system, part of the original disk from which the sun and planets formed. The craft is now so far from Earth that it takes six hours and eight minutes to receive a command sent from Earth.

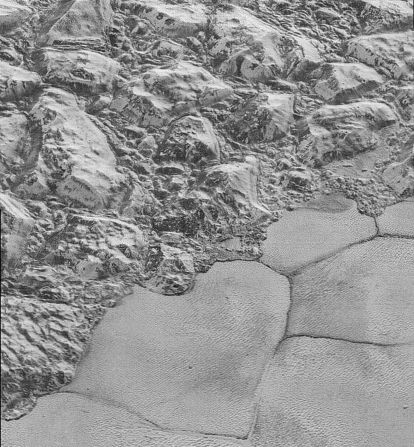

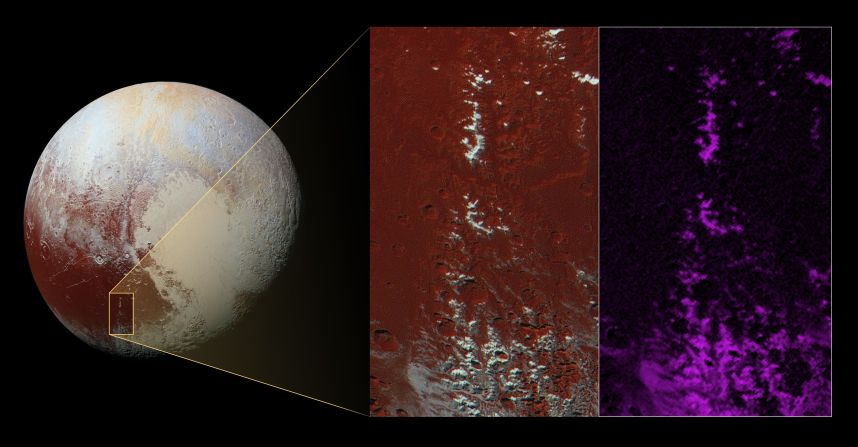

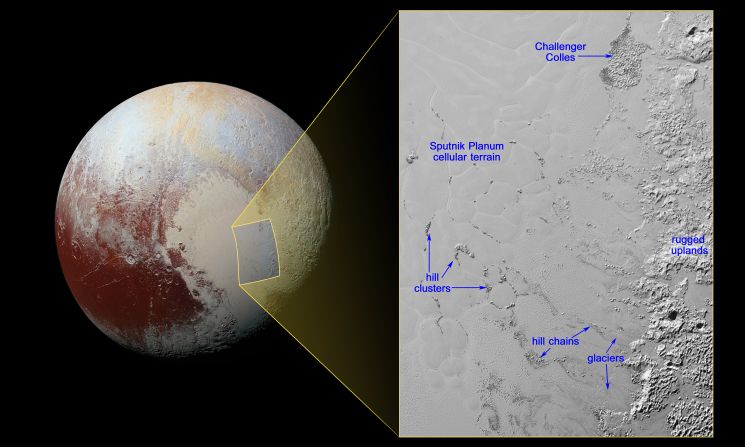

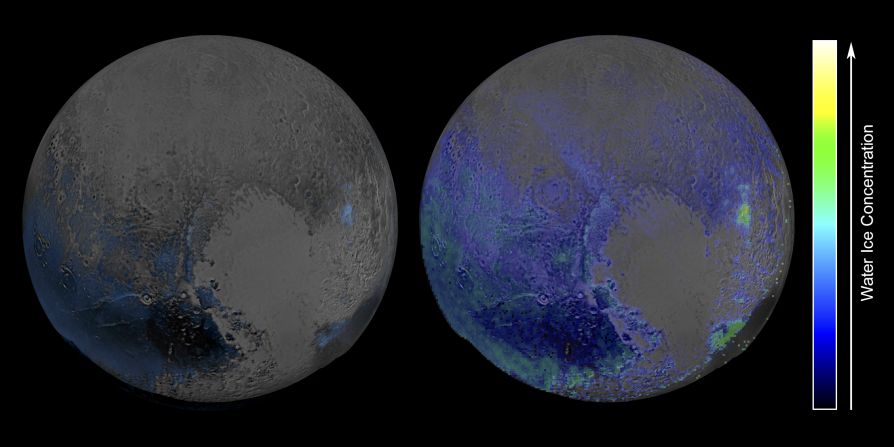

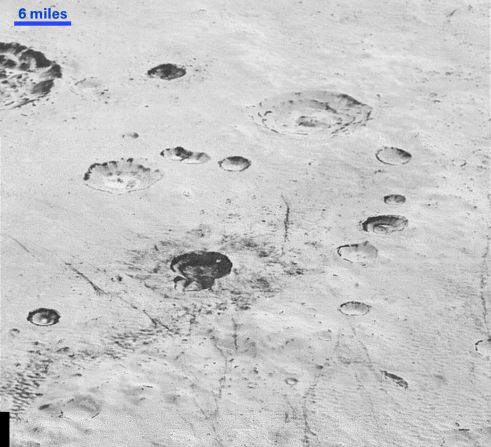

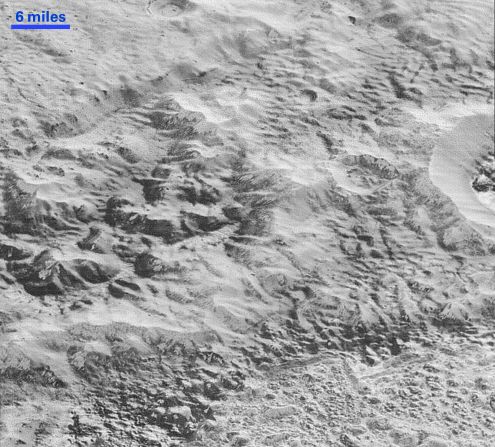

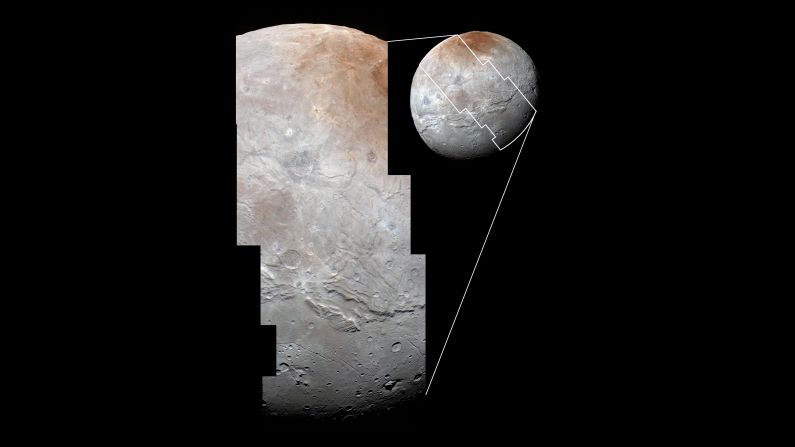

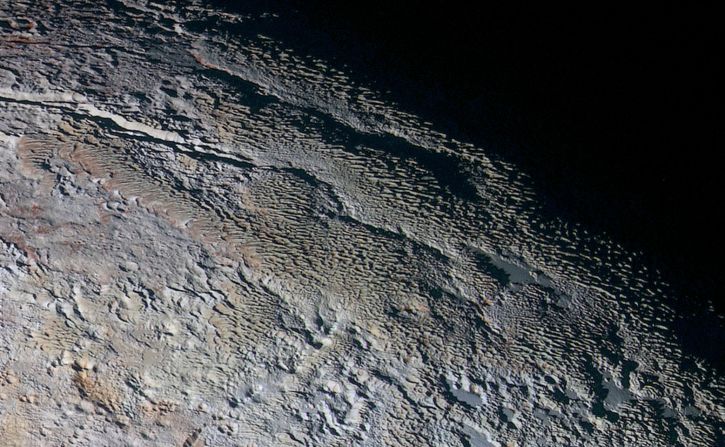

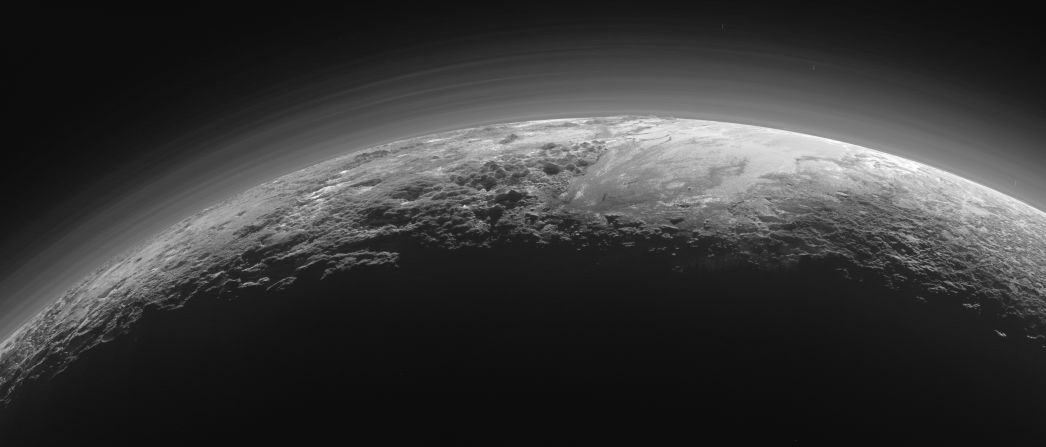

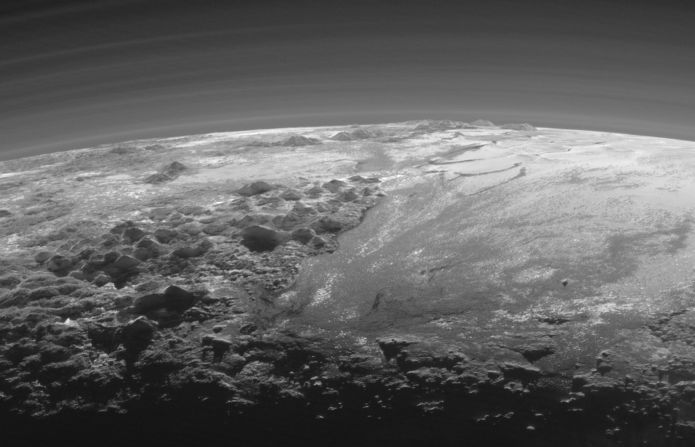

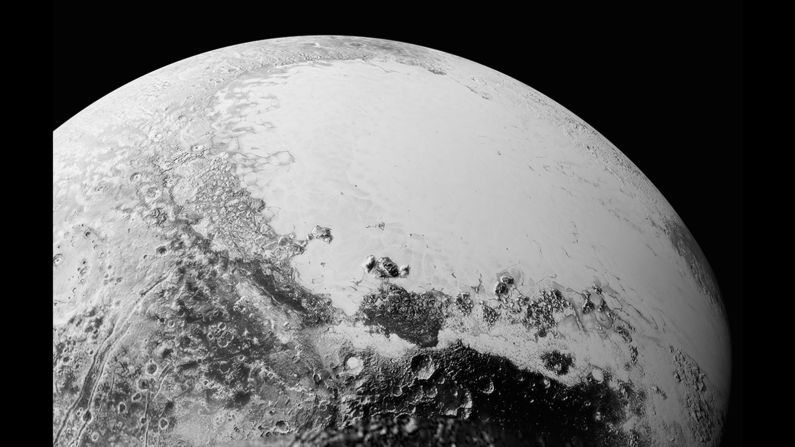

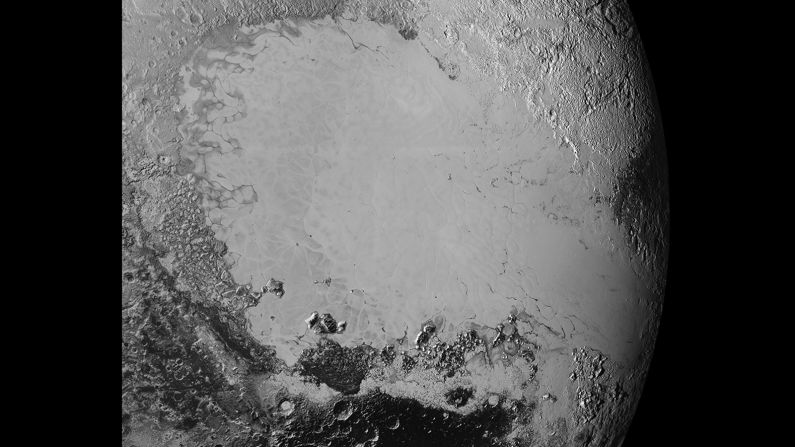

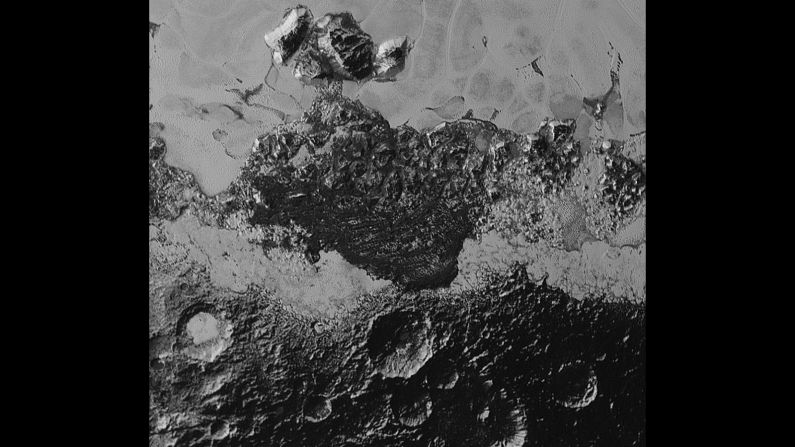

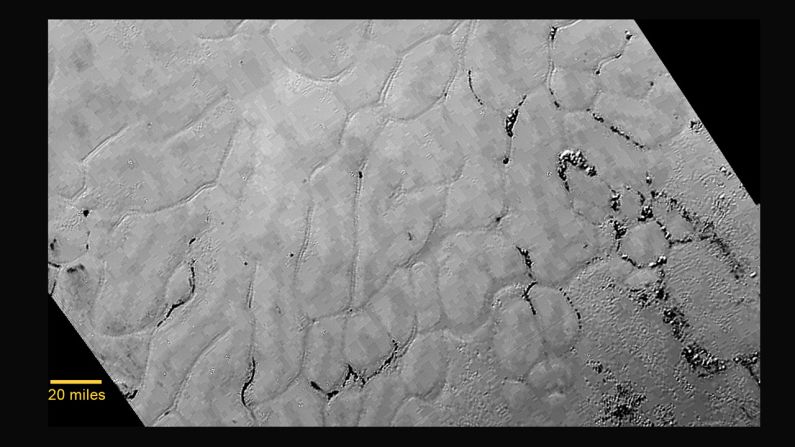

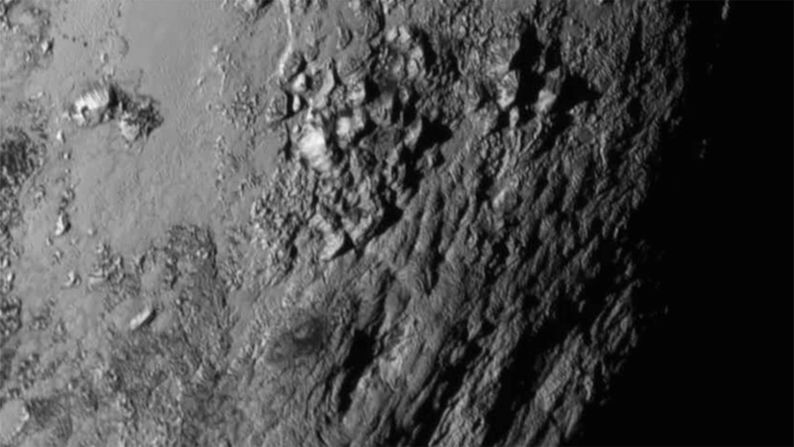

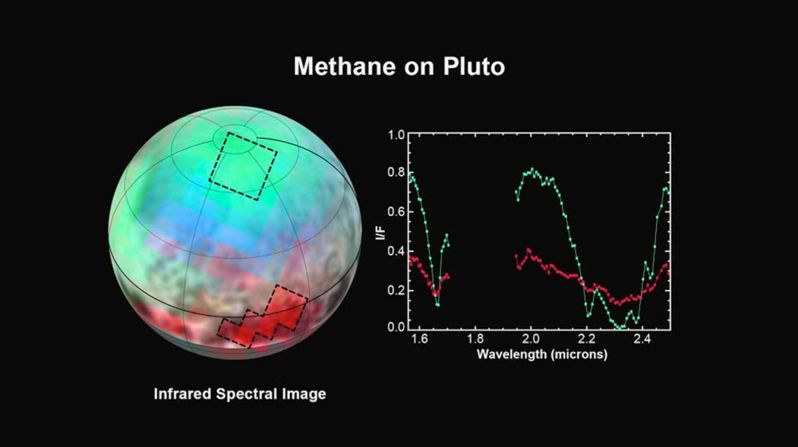

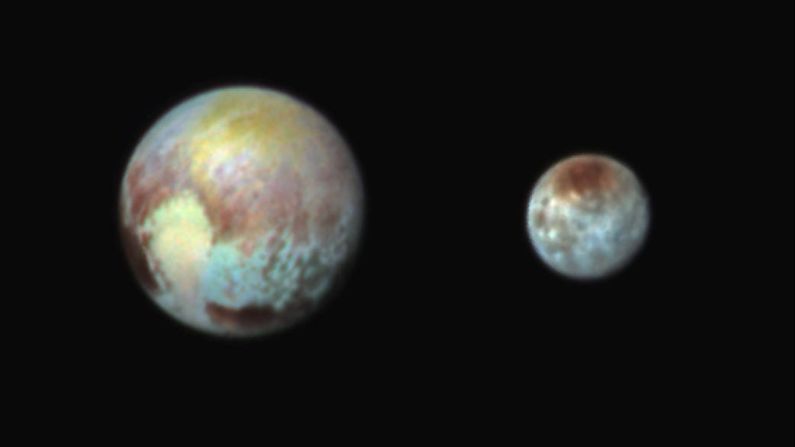

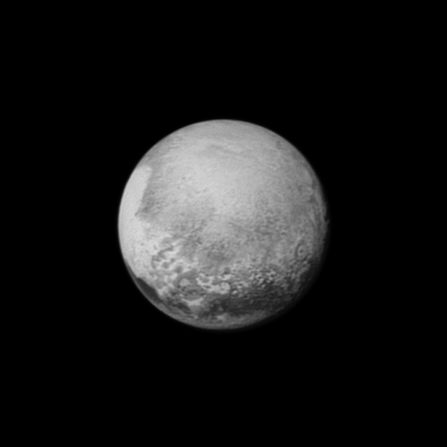

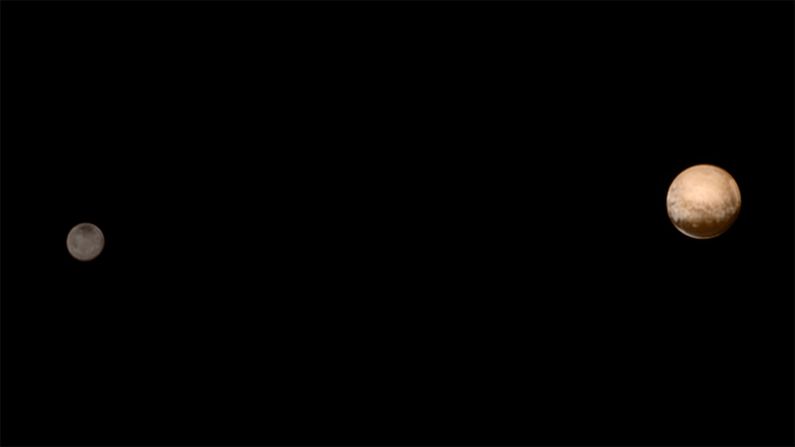

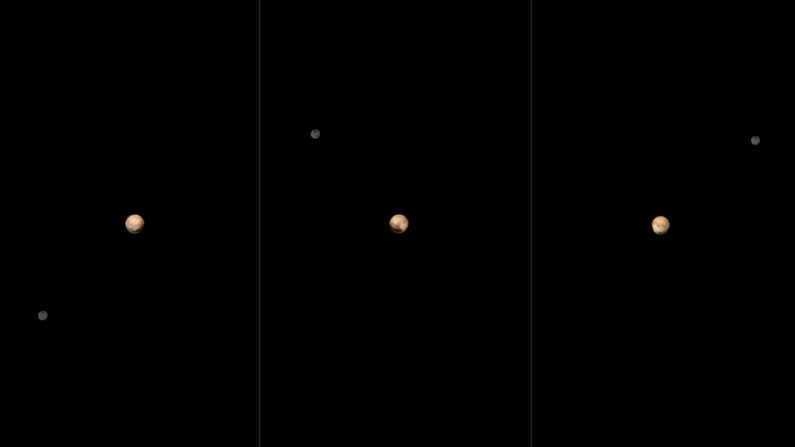

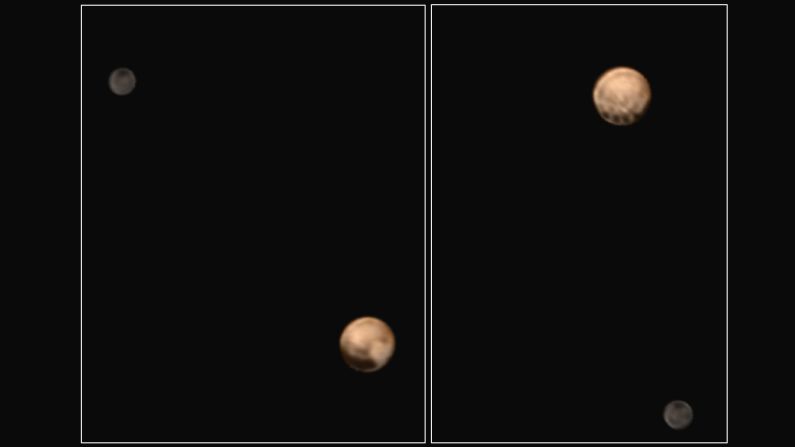

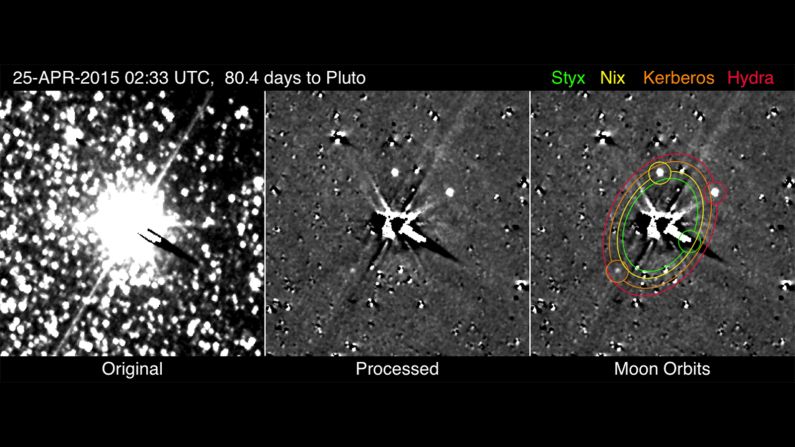

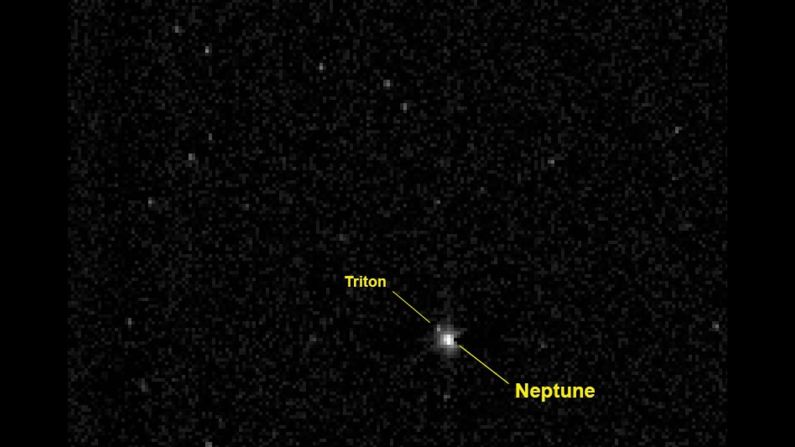

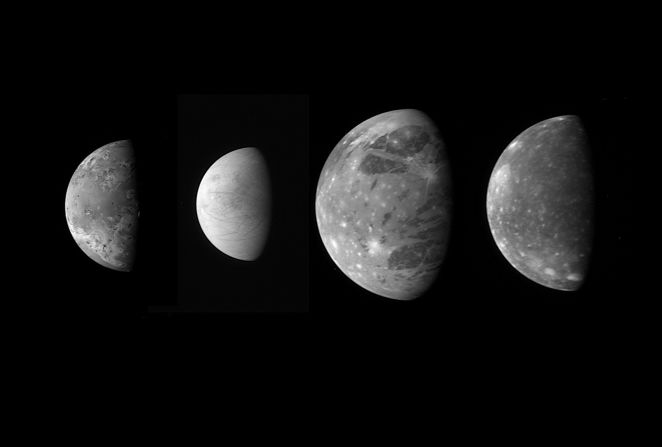

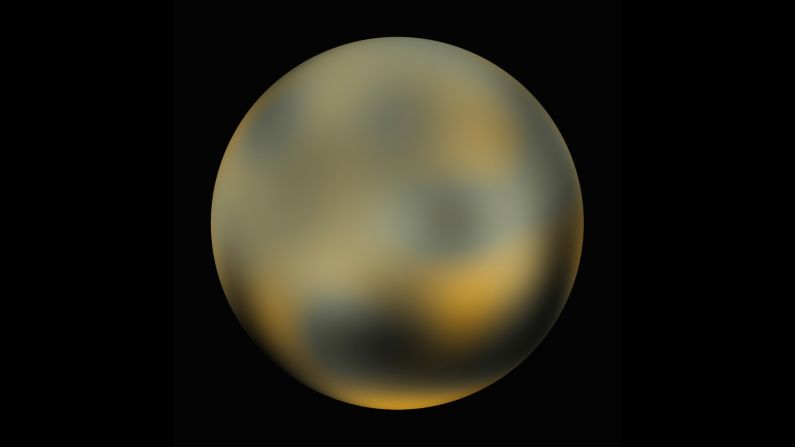

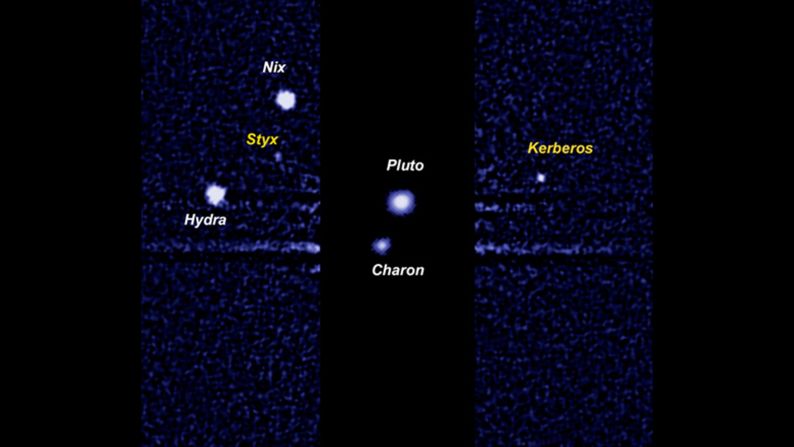

If New Horizons sounds familiar, it’s because this is the spacecraft that conducted a historic flyby of Pluto in 2015, sending back unprecedented images of the dwarf planet and revealing new details about Pluto and its moons. The New Horizons mission was extended in 2016 to visit this Kuiper Belt object. The mission was launched in 2006 and took a 9½-year journey through space before reaching Pluto.

New Horizons will fly three times closer to Ultima than it did by Pluto, coming within 2,200 miles of it and providing a better look at the surface. After the quick flyby, New Horizons will continue on through the Kuiper Belt with other planned observations of more objects, but the mission scientists said this is the highlight.

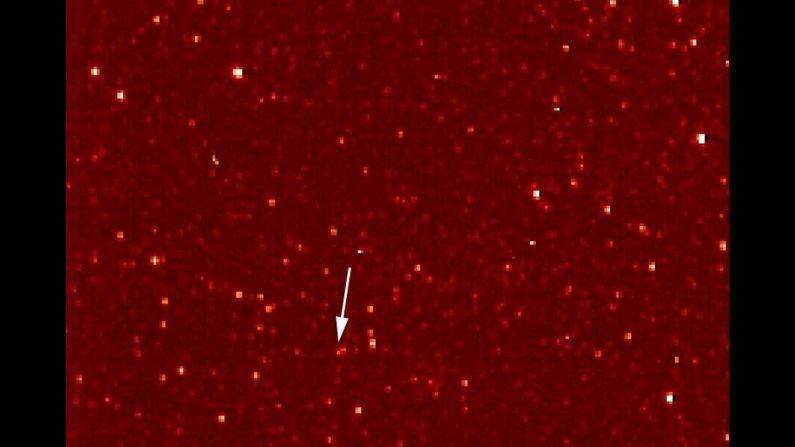

The object was previously known as 2014 MU69. The name Ultima Thule was chosen through a nickname campaign hosted by the New Horizons team.

Thule was a mythical island on medieval maps, thought to be the most northern point on Earth. Ultima Thule essentially means “beyond Thule,” which suggests something that lies beyond what is known. It’s fitting, considering New Horizons’ pioneering journey.

“MU69 is humanity’s next Ultima Thule,” Alan Stern, New Horizons principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute, said in a statement. “Our spacecraft is heading beyond the limits of the known worlds, to what will be this mission’s next achievement. Since this will be the farthest exploration of any object in space in history, I like to call our flyby target Ultima, for short, symbolizing this ultimate exploration by NASA and our team.”

Once the flyby happens and mission scientists understand more about just what Ultima Thule is, NASA will choose a formal name to submit to the International Astronomical Union.

And even though missions have flown through the Kuiper Belt, considered the third zone of the solar system, they weren’t able to explore it because scientists didn’t even know about it until the 1990s.

“The Voyagers and Pioneers flew through the Kuiper Belt at a time when we didn’t know this region existed,” Jim Green, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, said in a statement. “New Horizons is on the hunt to understand these objects, and we invite everyone to ring in the next year with the excitement of exploring the unknown.”

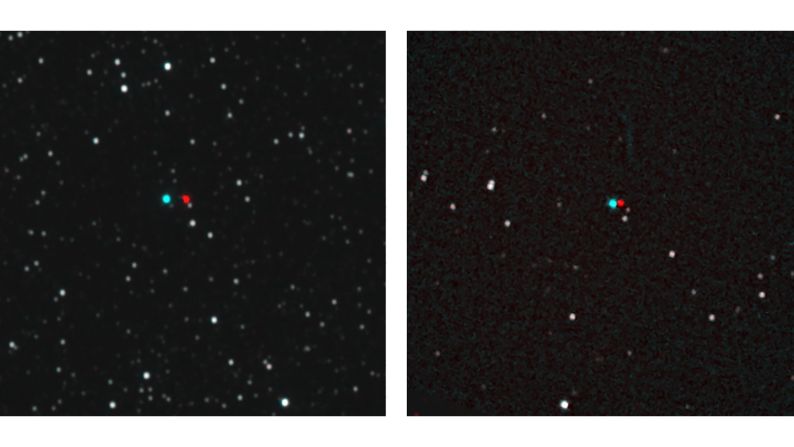

The Kuiper Belt is full of small, icy bodies and worlds, and we don’t know much about Ultima Thule. It was discovered in 2014 by the Hubble Space Telescope. In 2017, scientists determined that it isn’t spherical, but more elongated. Ultima could even be two objects, but only the flyby will tell for sure.

Based on its circular orbit, as opposed to the elliptical orbits of the planets, Ultima Thule formed 4 billion miles away in the middle of the Kuiper Belt. Temperatures here are close to absolute zero because the region is so far from the sun. Ultima is 100 times smaller than Pluto, and Pluto is about the size of the United States.

And rather than being like Pluto or the large planets in our solar system, Ultima Thule is a surviving planetary building block, primitive and pristine. It was never perturbed or moved, and it formed in an area where ice is as strong and hard as rock, so it never melted or formed a core. This will provide insight about what it was like as our solar system was forming 4.5 billion years ago and how small planets like Pluto formed.

The New Horizons mission was extended to observe Kuiper Belt objects after its Pluto flyby, with more than two dozen Kuiper Belt objects on the list. It will also measure the Kuiper Belt’s environment.

So what can we expect? As early as January 1, images and data will be sent back to Earth from New Horizons and its suite of instruments and cameras about seven hours after that closest approach.

After a “health status check” on the spacecraft, more images will start to appear January 2 and in the first week of the new year, which will tell whether Ultima Thule is sporting any rings, satellites or an atmosphere. And we can learn its composition.

“The Ultima Thule flyby is going to be fast, it’s going to be challenging, and it’s going to yield new knowledge,” Stern wrote on the New Horizons blog. “Being the most distant exploration of anything in history, it’s also going to be historic.”