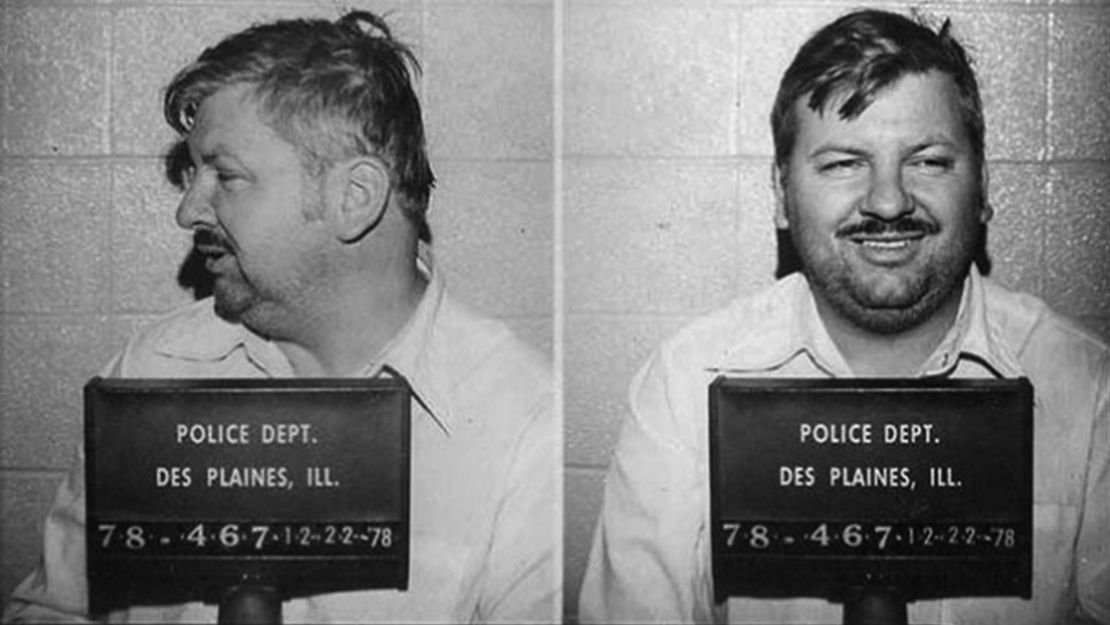

For more on John Wayne Gacy, watch HLN’s “Very Scary People” Sunday, March 17 at 9 p.m. ET/PT.

Lorie Sisterman remembers the last time she saw her brother. It was the summer of 1976, and the 16-year-old had just told his family he was headed to Chicago.

Their mother worked multiple jobs. Their dad was in and out of the picture. It was no big deal for the St. Paul, Minnesota, teen to take off for two or three days, visiting friends.

This time, though, weeks passed. Then months. Months became years became decades – four decades to be exact.

In 2016, Sisterman’s nephew found out investigators were trying to identify victims of one of America’s most notorious murderers: the “Killer Clown” known as John Wayne Gacy. He called Detective Sgt. Jason Moran with the Cook County Sheriff’s Office in Illinois.

“He says that his uncle has been missing for 35 or more years and he would like to learn if his missing uncle, Jimmy Haakenson, was one of Gacy’s victims,” Moran recalled.

Moran had been tapped to reopen the cold cases of Gacy’s unidentified victims. Though the serial killer had been executed for the murders of 33 boys and young men in 1994, eight victims were not identified.

The only reminder that their lives had not been forgotten were headstones placed on their Chicago graves reading, “We Remembered.”

Moran bore the weighty responsibility of putting names to those tragically lost lives and bringing closure to eight families.

‘Why don’t you wait a few days?’

In the freewheeling 1970s, Jimmy’s disappearance didn’t raise much suspicion. Young people enjoyed the “loose culture” of the times, said Moran, who grew up in Chicago during that era.

Plus, Jimmy had called his mom on August 5, 1976, to let her know he was OK. He’d be back soon, he told her.

“To go missing is not a crime, and back in the ’70s, it lent itself to a lot of missing person cases,” Moran said.

Family members would report their teenage sons and daughters missing, and police often had a pat response: “Why don’t you wait a few days? … If they’re still missing, we’ll come out and take a report,” Moran said.

For Jimmy’s mother, waiting wasn’t an option. Sisterman recalls joining her mother and a family friend on a trip to Chicago in hopes of finding Jimmy. They had no leads.

“It was a long shot,” she said. “We just went up and down streets. She was very anxious, hoping to pull a needle out of a haystack.”

They had no luck. Nor did they find any clues. As time passed, the family had no choice but to go on living. Sisterman grew up, got married and had kids. From time to time, she would revisit his vanishing.

“In the back of my mind occasionally I would wonder, ‘Where is Jimmy?’” she said.

The beginning of a break

Between 1972 and 1978, dozens of teenage boys and young men went missing in the Chicago area. Robert Piest, 15, was one of them.

Rob, as he was known, was an honor student. He’d gotten off work at a pharmacy in Des Plaines, 20 miles northwest of Chicago. His mother picked him up because he couldn’t drive.

It was December 11, 1978, her birthday, said Greg Bedoe, an investigator with the Cook County State’s Attorney’s Office at the time.

Inside the pharmacy, Rob told his mom there was acontractorin the parking lot who he wanted to talk to about a job.

“He grabbed his coat,” Bedoe said, “went out the door and vanished.”

For hours, Rob’s family searched for him. Along the way, they learned the contractor’s name was John Wayne Gacy.

“They notified the police at about 11 p.m.,” said Bob Egan, who was a Cook County prosecutor in 1978.

Like Jimmy’s family, they were told to wait till morning, to give it some time, Egan said. Also like Jimmy’s family, the Piests were scared and had no such patience on hand.

The next morning might be too late, the family worried. Their fear was not assuaged by a police background check that revealed Gacy had nine years earlier pleaded guilty to sodomy, a crime at the time in Iowa, for an incident involving a teenage boy. He served 18 months of a 10-year sentence.

Police went to Gacy’s house the day after Rob went missing, Egan said.

‘Catch me if you can’

The community knew Gacy well. He owned a construction company, hosted parties and was active in the Democratic Party, serving as a local precinct captain. As leader of Chicago’s Polish Constitution Day Parade, he was photographed with first lady Rosalynn Carter.

Gacy invited police into his home. He’d been at the Des Plaines drug store, he told them, but he didn’t remember talking to Rob Piest, Egan said.

As they chatted, the teen’s body – Gacy’s last victim – lay in the attic above them.

Doubting his story, police returned the next day with a search warrant, but there was no sign of Rob.

There were, however, items that piqued officers’ suspicions: handcuffs, fake badges and sex literature involving minors. In a garbage can, they also found a photo receipt from the pharmacy where Rob worked.

Many of the bizarre items appeared to have no connection to Rob or Gacy, including temporary driver’s licenses and a high school class ring, Bedoe said.

“Who are these people? What are these pieces of identification? Where did this stuff come from?” Bedoe wondered.

Despite the curious nature of the items, nothing constituted probable cause for an arrest, no matter how cavalier Gacy seemed about police searching his home.

“We knew he was guilty. He was dirty, something,” Bedoe said. “And he acted as if – catch me if you can.”

Authorities began a 24/7 surveillance effort. Gacy later invited two of the detectives keeping watch into his home. One of the investigators asked to use Gacy’s bathroom and while doing so smelled decomposition wafting through a vent.

Bedoe and Des Plaines investigators, meanwhile, were interviewing employees at Gacy’s construction company. They learned other young men had gone missing, including John Butkovich and Gregory Godzik, who worked for Gacy, and John Szyc, who disappeared after meeting Gacy to sell a car, Bedoe said.

The employees were “never reported seen alive again. No bodies were recovered. They vanished from the face of the Earth. Where are they? Where did they go?” the former investigator said.

A map of disturbing precision

Gacy’s employees further told police that Gacy had asked them to dig trenches in his crawl space to manage a drainage problem.

“The digging, the piles of dirt, these kids are never seen or heard from again. Where are they? Well, is it possible that they’re in the crawl space?” Bedoe asked.

If so, detectives were no longer investigating a few disappearances. They were investigating a serial killer.

When a judge granted a second search warrant, Gacy was already in custody. Fearing he was a suicide risk, police had arrested him on a marijuana charge to keep an eye on him.

On December 21, 1978, police returned to his Norwood Park home. Egan remembers a crime scene technician yelling upstairs from the crawl space.

“Oh shit!” he said.

“What’s wrong?” detectives replied.

“I’ve got another rib cage down here.”

Back in Des Plaines, Gacy was confessing to a gruesome killing spree. He told officers how he lured victims to his home, tricked them into putting on handcuffs and strangled them, Egan said.

The killer mapped his crawl space with alarming detail, sketching out a homemade graveyard.

“He said, ‘You’ll find four bodies here, two on top of two, and under the door you’ll find three placed next to each other. Under the kitchen, you’ll find five, three and then two next to them,’” Egan said.

Twenty-seven victims were excavated from the crawl space. Another was under his garage, and there was one more in his back yard.

After running out of room in his crawl space, Gacy told investigators, he threw four more bodies from the Interstate 55 bridge into the Des Plaines River.

Families struggle with what to do

Four hundred miles away, in St. Paul, Lorie Sisterman was following the investigation. Hoping for answers, the family filed another missing person’s report.

At the time, dental records were the best way to identify victims. The Haakensons didn’t have Jimmy’s. Their case went cold again.

In 1980, Gacy was convicted of murdering 33 boys and young men, making him, at the time, the most prolific serial killer in U.S. history. His execution came 14 years later.

For many families, it brought closure, but eight victims remained unidentified in eight Chicago cemeteries beneath the “We Remembered” gravestones.

Detective Sgt. Moran and Sheriff Thomas Dart reopened the cases in 2011 to identify the victims using DNA technology.

Moran’s sympathy for the victims’ families runs deep.

“They’re some of the saddest people that you want to talk to, and the reason is because they live in a cruel limbo,” he said. “They don’t want to think that their missing loved one is dead because then, it’s like they’re giving up hope.”

They struggle with matters as seemingly simple as what to do with their loved ones’ belongings, he said.

“Especially after 10, 20, 30 or 40 years, if you throw their belongings away, it’s like you’re throwing them away.”

Two victims get their names back

The identification process is complex. Investigators first extract DNA samples from victims and establish a profile of potential victims: young white males with slight builds who disappeared in the Chicago area between 1972 and 1978.

Then comes the most difficult phase: finding a match, which entails locating family members willing to submit DNA.

“The public coming forward would allow us to do DNA matches that were not possible 30 years ago,” Dart explained at a 2011 news conference.

Within six weeks, police had a match.

“Victim No. 19 is never going to be known by a number anymore. Victim 19 was William George Bundy,” the sheriff said.

Optimism soared that more victims could be identified, but the phones quickly went silent and leads grew cold – until Sisterman’s nephew called Moran from Texas. Jimmy Haakenson had disappeared amid Gacy’s killing spree, he told the detective.

Sisterman and Jimmy’s other brother provided DNA samples. The analysis took weeks, and when Moran received the report, he drove to St. Paul to speak directly with the family.

“I was sorry to report that their missing brother and uncle was murdered by John Gacy,” Moran recalled telling them.

Sisterman and the family were stunned. Jimmy’s mother had died before the family found out.

“People were crying. My brother and I, we did not cry,” she said. “I think we were both in a state of shock.”

The family had been waiting 40 years for Jimmy to come home. Now, they could stop waiting, but for Sisterman, resolution will never mean closure.

“I still want him back,” she said. “I want my brother back.”

Heartbreak and serendipity

Moran’s work is grueling. Leads fizzle. Cases go unresolved. Victims can’t be found.

“In my job and detective work overall, being successful sometimes causes other people pain,” he explained.

But Moran has also been able to close 13 cold cases during the investigation, he said.

“I have been able to identify more non-Gacy victims than Gacy victims through this,” he said.

He’s also found people who were alive after being missing for 35 years. “So I try to follow the lead, follow the case to its resolution,” he said.

Moran, in many ways, battles his own cruel limbo.

“I try not to make it personal, and I don’t say it haunts me, but it does occupy my space.”

And with six victims left, there’s more work to do.

“There’s many times where I sit up thinking or feeling something about the cases I’m involved in,” Moran said. “You try not to, but it’s no end. You can’t stop sometimes.”

CNN’s Courtney Yager and Jean Casarez contributed to this report.