The pilots of Lion Air Flight 610 were engaged in a futile tug-of-war with the plane’s automatic systems in the minutes before it plunged into the ocean, killing all 189 people on board.

But investigators say they are at a loss to explain why the pilots didn’t follow the same procedure performed by another flight crew the previous day when they encountered a similar issue.

A preliminary report into the crash released Wednesday by Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee (NTSC) reveals more details about the final moments of Flight 610, but acknowledges many questions remain.

Data retrieved from the flight recorder shows the pilots repeatedly fought to override an automatic safety system installed in the Boeing 737 MAX 8 plane, which pulled the plane’s nose down more than two dozen times.

The system was responding to faulty data, which suggested that the nose was tilted at a higher angle than it was, indicating the plane was at risk of stalling.

According to the report, the pilots first manually corrected an “automatic aircraft nose down” two minutes after takeoff and performed the same procedure again and again before the plane hurtled nose-first into the Java Sea.

CNN aviation analyst David Soucie said that the circumstances created by the plane’s automatic correction would have made pilot intervention “impossible.”

“The fact that they fought against the MCAS (multiple) times with the trim settings was an impossible scenario to recover from,” he said.

Problem previously corrected

A different flight crew had experienced the same issue on a flight from Denpasar to Jakarta the previous day, but had turned off the automatic safety feature, known as the maneuvering characteristics augmentation system (MCAS) and took manual control of the plane.

The feature is new to Boeing’s MAX planes and automatically activates to lower the nose to prevent the plane from stalling, based on information sent from its external sensors. Indonesian investigators have already pointed to issues with the plane’s angle-of-attack (AoA) sensors, which had proved faulty on earlier flights.

AoA sensors send information to the plane’s computers about the angle of the plane’s nose relative to the oncoming air to help determine whether the plane is about to stall.

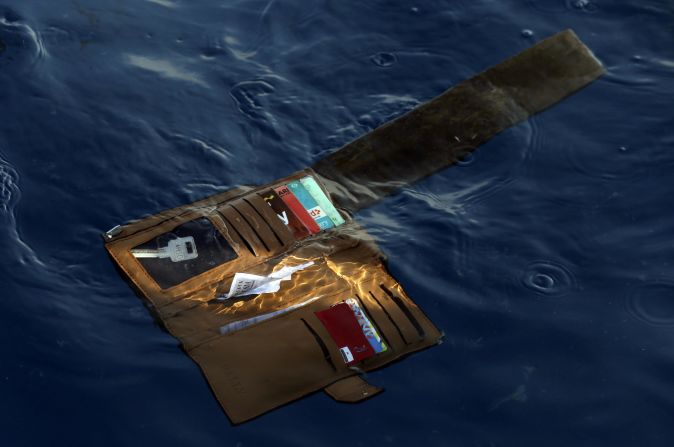

In photos: Lion Air plane crashes off Indonesia

Responding to the report, Boeing said it was “deeply saddened” by the loss of the Lion Air flight – but maintained the 737 MAX 8 “is as safe as any airplane that has ever flown the skies,”and that the company is “taking every measure to fully understand all aspects of this accident.”

Wednesday’s preliminary report recommends that Lion Air review its safety culture while the investigation continues, and while officials search for cockpit voice recorder (CVR), which is believed to be buried under mud on the ocean floor.

It should reveal what the pilots were saying and why they didn’t turn off the safety feature.

“We need to know what was the pilot discussion during the flight. What was the problem that may heard on the CVR. So why the action difference, this is the thing we need to find. At the moment I don’t have the answer,” said the NTSC’s head of aviation, Capt. Nurcahyo Utomo.

Issue reported two minutes into flight

The preliminary report said Flight 610 reported a issues minutes after taking off from the Indonesian capital on October 29 en route to the city of Pangkal Pinang, on the island of Bangka.

Within 90 seconds of takeoff, the co-pilot asked air traffic control to confirm air speed and altitude. Thirty seconds after that he reported that they had experienced a “flight control problem,” the report said.

After the aircraft’s flaps retracted following takeoff, the automatic trim problem noted on the previous night’s flight returned, until the flight data recorder stopped recording when the plane crashed.

The report said the pilots on the plane’s penultimate flight reported that instruments were showing inaccurate readouts from the angle-of-attack (AoA) sensors.

The report said that the plane was “automatically trimming” on the previous flight – that is, the computer was adjusting the aircraft’s angle – so the pilots switched to manual trim and, as their safety checklists didn’t recommend an emergency landing, they continued to Jakarta.

Further maintenance on the AoA sensor was carried out in Jakarta prior to Flight 610’s takeoff the next morning. After the flight took off, the instruments recorded a substantial discrepancy in the aircraft’s angle – as much as 20 degrees.

Aviation expert Geoffrey Thomas called the report “very comprehensive” and said that he could not understand why Lion Air had deemed the plane suitable for service.

“Clearly the plane had serious sensor issues … why the airplane wasn’t pulled out of service beggars belief,” he told CNN.

“Tinkering around and replacing parts isn’t enough.”

As part of the continued investigation, the faulty AoA sensor will undergo further testing, the NTSC said. It plans to finish its report within 12 months.

Captain’s mother: Son said sim training unnecessary

The pilot’s mother Sangeeta Suneja, herself a senior commercial manager with Air India, told CNN after a family briefing Tuesday that her son was “a sunny boy. He was loved by everybody in his company.”

She says her son, Capt. Bhavye Suneja told her there was no updated training simulation session when Lion Air started using the new aircraft.

“They said it was not required… When the transition happened, he said, ‘Mama, I’m going to fly the MAX.’ I said, ‘How can you do that (when) you don’t have (a) simulator session?’ He said, ‘We don’t need to.’”

Coming from an aviation family, she said that Suneja’s sister wanted to follow in his footsteps, but that the fatal accident had shaken her faith in the technology.

“Even my daughter wants to be a pilot. She was so inspired by him she also wants to be a pilot,” she said.

“Now I have apprehensions. I don’t know. How safe it is. The trust in the machine is shaky now.”

She added that air safety regulation across the world needed to be re-established to reaffirm people’s trust in air travel.

“Whenever they (present new aircraft) to the market, where the life of the people is at stake, the regulators must re-establish three, or five, levels of crosscheck… Someone should have questioned this.”

Complaints about Boeing manual

The Allied Pilots Association (APA) and Lion Air’s operational director claim Boeing’s operational manual for the MAX 8 did not contain adequate information about the MCAS system.

“We don’t receive any information from Boeing or from (the) regulator about that additional training for our pilots,” Zwingli Silalahi, Lion Air’s operational director told CNN on November 14. Both the pilot and co-pilot of Flight 610 were experienced, the airline has said, with 6,000 and 5,000 flight hours respectively.

Boeing stood by the aircraft’s safety record. “We are confident in the safety of the 737 MAX. Safety remains our top priority and is a core value for everyone at Boeing,” a spokesperson said.

The parents of one passenger is suing Boeing, alleging the 737 MAX 8 had an unsafe design. The suit alleges Boeing failed to communicate a new safety feature that hadn’t existed in previous 737s.

Boeing released an operational bulletin on November 6, a week after the crash, warning all airlines about how to address erroneous readings related to the plane’s external sensors. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) later issued its own directive that advised pilots about how to respond to similar problems.

Earlier this month, Indonesian investigators who examined the jet’s flight data recorder said there were problems with the air speed indicator on the three flights before the crash.

The plane was intact with its engines running when it crashed, at more than 450 mph (720 kph), into the Java Sea, Soerjanto Tjahjono, head of Indonesia’s National Transportation Safety Committee, said at the time.

Tjahjono said that due to the small size of the debris found and loss of the plane’s engine blades, investigators determined that Flight 610 did not explode in the air, but was in “good shape” before it crashed 13 minutes after takeoff.

Journalist Masrur Jamaluddin in Jakarta contributed to this report.