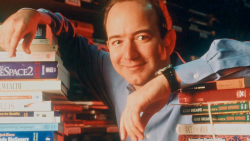

Cities should resist the temptation to throw money at Amazon and CEO Jeff Bezos just because the company is promising to create high-paying jobs. That’s the message from progressive groups and some local policymakers in New York City and Washington.

In a 14-month frenzy, cities across North America bent over backward to court Amazon’s second headquarters, or HQ2, by offering subsidies and tax breaks. Recent reports suggest Amazon might split its the new office campuses between Long Island City in Queens and Crystal City in Arlington, Virginia.

The company has pledged to spend at least $5 billion and create 50,000 jobs as part of the project. Even divided over two locations, that represents an enormous infusion into a local economy.

But as Amazon’s decision (AMZN) nears, opposition to cities’ huge packages of economic incentives is getting louder. Groups organizing to pressure local leaders say financial sweeteners are unnecessary due to Amazon’s size and wealth, and they think the money would be better spent on services for the community.

“We’re going to do everything we can to fight Amazon coming to New York, and [to stop] any benefits that our mayor and our governor might lavish on them,” said Jonathan Westin, executive director of New York Communities for Change, an advocacy group that supports low-income communities in the region.

Amazon has long been a target of liberal advocates. They have protested its record on pay and work conditions at its warehouses and blame the company for the gentrification of its home city, Seattle. Senator Bernie Sanders has slammed the company’s treatment of workers, though he ultimately supported Amazon when it said it would instate a $15-an-hour minimum wage for US employees last month.

Now the with the possible arrival of new Amazon headquarters in Long Island City and Arlington, the activist fight is spreading — and some local officials are on the activists’ side.

“My understanding is the public subsidies that are being discussed are massive in scale,” New York state senator Michael Gianaris, who represents the Long Island City area, told CNN Business. “Why we would need to give scarce public dollars to one of the richest companies on Earth is beyond me.”

The terms of the proposals to Amazon from New York City and the Washington area haven’t been disclosed, so it’s uncertain what exactly is on the table. However, precedent and public statements indicate that Amazon could get generous deals in exchange for investment and jobs.

On Monday, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo said that he would change his name to “Amazon Cuomo” if it meant the company would pick New York for HQ2. “I am doing everything I can,” he told reporters, adding that New York has “a great incentive package.” Cuomo is working directly with Amazon to try to bring Amazon to Long Island City, a senior New York government official with knowledge of the negotiations told CNN.

Cuomo’s enthusiasm might not trickle down. Local elected officials have taken to speaking out against a potential deal.

“The lack of transparency in this process is outrageous,” local councilman Jimmy Van Bramer said in a statement Thursday.

New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio has called securing HQ2 a “tremendous opportunity,” but conceded this week that “there are real development pressures to be navigated.” He said the city would not award Amazon any special incentives beyond what’s available to all companies and developers.

“I want to differentiate the state and the city — the city is not providing subsidies,” he told reporters Tuesday. “We do not believe in subsidies to corporations for retention or to attract corporations.”

For state senator Gianaris, incentives aren’t the only issue. He also wants to know what Amazon intends to do to ease stress on the area’s schools and strained subway system. “This is a neighborhood that’s already being overdeveloped,” he said.

Activists say they have similar concerns about Amazon as they do about Walmart (WMT). Progressive groups have successfully kept Walmart out of New York City for decades, citing their treatment of low-wage workers and harm to smaller businesses.

“We believe Amazon is just the next iteration of what Walmart was,” said Westin of New York Communities for Change.

Such points of view have also bubbled up in the Washington area. A group called “Obviously Not DC,” supported by activist group Fair Budget Coalition and the D.C. chapter of the Democratic Socialists, has a simple tagline: “Fund our communities, affordable housing, schools, and transit. Not Amazon.”

Massive incentive packages are a popular tool to lure large development projects, said Megan Randall, research analyst at the Tax Policy Center. The problem is, such packages often lack the proper accountability measures to make sure promised economic benefits materialize, she said. It’s also not clear that businesses prioritize incentive packages when making decisions about where to locate, she added.

“Tax incentives, the research shows, actually play a fairly secondary role in terms of where firms decide to go,” Randall said.

Issues with hefty economic incentives came up when Foxconn, the Taiwanese Apple supplier, announced in 2017 it would invest $10 billion to build a plant in Wisconsin. It pledged to create as many as 13,000 jobs by 2020, and was awarded more than $4 billion in incentives in return.

This week, the Wall Street Journal reported Foxconn is having trouble finding the engineers it will need at the plant, and that it is trying to get staff at some of its plants in China to move. Foxconn denied the report.

Even so, economic incentives are a common part of development deals. For cities, it’s difficult not to throw in perks like tax breaks and subsidies if competing regions are offering them.

“It’s hard to tell if the questions that the public and policymakers are asking are going to become a feature of the discussion,” Randall said. “or if tax incentives are going to retain their popularity.”

CNN’s Alison Kosik contributed to this report.