From the jungles of Myanmar to the streets of Hong Kong, police throughout Asia are fighting a war against methamphetamine.

By many indications, they’re losing.

Demand for both crystal meth and yaba, tablets that typically contain a mixture of meth and caffeine, is skyrocketing. Production is increasing at an unprecedented clip, and so is the body count. Leaders in places like Bangladesh and the Philippines are waging deadly drug wars that have cost thousands of lives.

But this isn’t “Breaking Bad” – meth isn’t just used by the poor and the downtrodden.

Meth no longer discriminates in Asia; it has become the dominant drug of choice across the region, irrespective of class, age or gender, according to Jeremy Douglas, who is in charge of United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) southeast Asia operations.

In a career spanning 16 years, Douglas said he’s never seen demand like this.

“No situation is exactly comparable, but this is off the charts,” he said.

Experts say the boom is due to a serendipitous combination of domestic and geopolitical issues that have aligned to the benefit of the region’s drug gangs.

The majority of meth production is happening deep inside the jungles of the Golden Triangle, a lawless area where the borders of Thailand, Laos, and Myanmar meet. Experts say it’s easy to conceal drug production there and move it on at short notice.

Drug runners, meanwhile, are exploiting new roads and infrastructure being built as part of an ambitious, trillion-dollar Chinese initiative to connect markets across the globe, using the flow of people and licit goods to mask drug trafficking.

And the profits, likely worth hundreds of millions of dollars, are being laundered via intricate international schemes, often using front companies in countries where lax oversight makes it easy to hide money.

“It’s a perfect storm in terms of the production of methamphetamine,” says John Coyne, a former head of strategic intelligence at the Australian Federal Police who now works on border security issues at the Australia Strategic Policy Institute.

“It’s pushing Southeast Asia into what could be in time a methamphetamine epidemic.”

Production

A large portion of meth seized throughout the Asia Pacific region has been traced to Myanmar’s northern Shan State, where militias and warlords reign supreme.

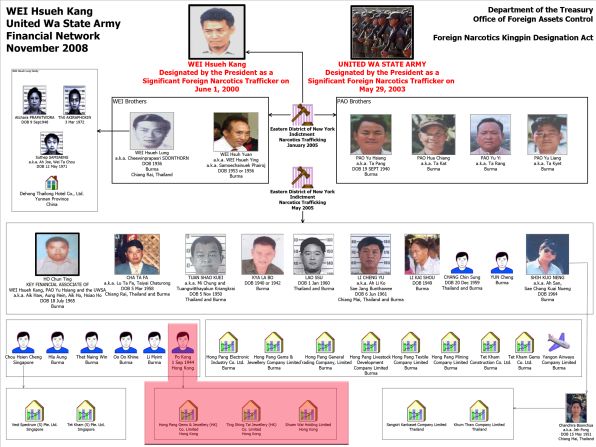

Perhaps the most prominent is the United Wa State Army (UWSA) and its political wing, the United Wa State Party (UWSP).

The two have waged a years-long struggle for autonomy for the ethnic Wa population, people who share a common language as well as cultural and historic ties with their neighbors in China’s southern Yunnan province.

Shan State boasts a compelling combination of a good poppy-growing climate and a dearth of law enforcement. For years, the Golden Triangle was the source of the majority of the world’s illegal heroin and opium.

Authorities in the West have long accused the UWSA and UWSP of funding their armed struggle against the Myanmar central government with the profits from drug production. The UWSA is believed to boast around 30,000 fighters.

Verifying either claim is incredibly difficult. Northern Shan State is one of the hardest places in the world to access; some joke it’s easier to get into North Korea. The UWSA granted journalists a rare visit to the region in 2016, during which time they denied allegations of narcotics trafficking.

Official numbers appeared to lend credence to the claim that the UWSA is no longer producing heroin, at least at first glance. Golden Triangle heroin production and distribution has been on the decline, according to numbers from the United Nations.

Authorities warn that’s likely because the big players have ditched heroin in favor of a new, cheaper to produce alternative: methamphetamine.

“There’s a lot of evidence coming together from across the region pointing back to the same groups, pointing back to the same locations,” said Douglas with the UNODC.

The UWSA’s decision to get into the meth game, experts say, is partly a response to market forces, but it’s also motivated by profit and ease of production.

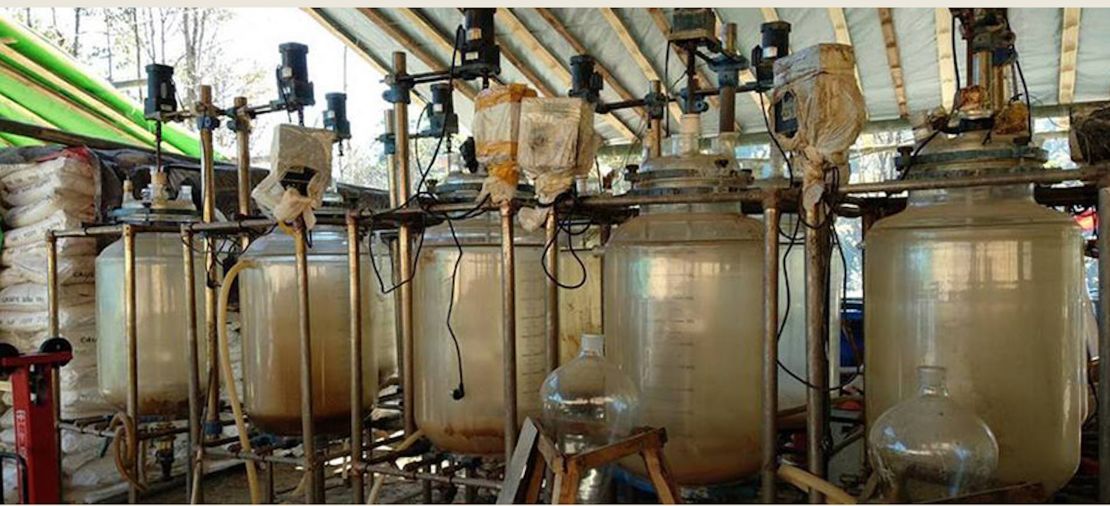

Methamphetamine is a synthetic drug. It’s made in a lab using chemicals and doesn’t require drug makers to cultivate organic crops, such as poppies, as is the case with heroin.

These labs can be covered by a tarp or moved on short notice. You can’t do that with a poppy field.

Distribution

Once the meth is made, the next challenge is transportation. The Golden Triangle was for years one of the most impoverished and underdeveloped places on the planet, but that’s changing thanks to China’s One Belt One Road initiative – a massive infrastructure development project intended to help connect global, predominately developing economies.

Beijing has big plans in Myanmar, where it has spent billions to connect China’s landlocked Yunnan province to port cities in South and Southeast Asia. Laos and Thailand have seen similar investments.

An unintended side affect of these infrastructure improvements is that they’ve made it easier for meth traffickers to transport product from deep inside Shan State to the rest of Southeast Asia, Coyne said.

“What you’ve got is a large, legitimate trade of people, goods, etc., flowing out of Myanmar and Laos in which you can hide your drugs,” said Coyne.

Meth from northern Shan State in both crystal and pill form has been found as far away as Japan, New Zealand and Australia. A record 1.04 billion Australian dollars ($800 million) worth of meth, believed to have originated in Shan State, was found by police in Western Australia in December.

This year, authorities have conducted dozens of meth seizures in Thailand, China, Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia and Indonesia.

Shockingly, it only took five months for seizures in Malaysia and Myanmar to surpass the 2017 totals, according to Douglas.

While those busts could mean law enforcement is winning its fight against traffickers, it also shows the sheer quantity of meth being moved.

Coyne warns of another possibility – that meth producers have gone into overproduction, which drives down the per unit cost of making drugs, which in turn makes it easier for dealers to live with these massive busts.

“They can afford to lose larger quantities and still make profits,” he said.

Laundering

All that money has to go somewhere, and law enforcement say drug dealers are using intricate financial networks to hide their ill-gotten gains.

The most prominent – at least publicly – is the case of the Zhao Wei, a gambling magnate accused by the US government of using his casino in Laos to help the UWSA launder proceeds from the sale of meth.

Casinos are used for laundering because they involve so much cash trading hands, but Zhao has the added benefit of operating inside what Douglas at the UNODC calls a “criminal mini-state.”

“It operates like his personal fiefdom,” Douglas said.

Zhao has reportedly negotiated a 99-year lease with the Lao government to operate what’s known as the Golden Triangle Special Economic Zone. The zone lies along the Mekong River that flows between Thailand, Myanmar and Laos. At its center sits the Kings Romans casino.

Zhao’s agreement with the Lao government allows his business to operate under its own set of unique laws, rules and regulations.

The only areas in which Zhao defers to the central government are on matters related to the military, the judiciary, and Lao foreign policy, Zhao told Chinese state media in 2011.

The system is ostensibly designed to help attract foreign investors into the special economic zone. However, the US Treasury Department imposed sanctions on Zhao and the casino in January, alleging that Zhao uses the lax regulation to help facilitate “the storage and distribution of heroin, methamphetamine, and other narcotics for illicit networks, including the United Wa State Army, operating in neighboring Burma.”

Zhao has persistently maintained that the accusations leveled against him are “groundless.”

“The US government’s unilateral sanctions on other countries and regions is unreasonable and ridiculous behavior and for other purposes. Such behavior has created profound misunderstanding for the world community thus causing unnecessary concern for a number of investors and visitors,” he said in February, shortly after the Treasury Department ruling, according to Lao state media.

“The Kings Romans Group’s investment and development strictly complies with the law and signed agreements. There are neither reasons nor motivations for us to run illegal businesses. On the contrary, we have cooperated with the government of Laos to prevent and combat strictly illegal acts.”

The Lao Ministry of Planning and Investment did not respond to CNN’s request for comment, and the US Drug Enforcement Agency declined CNN’s request for an interview for this story “due to some ongoing activity related to the case.”

Cashflow

The US Treasury Department, which did not respond to CNN’s request for comment for this story, alleges that a key cog in Zhao’s operation sits thousands of miles away from his casino in the hustle and bustle of Hong Kong.

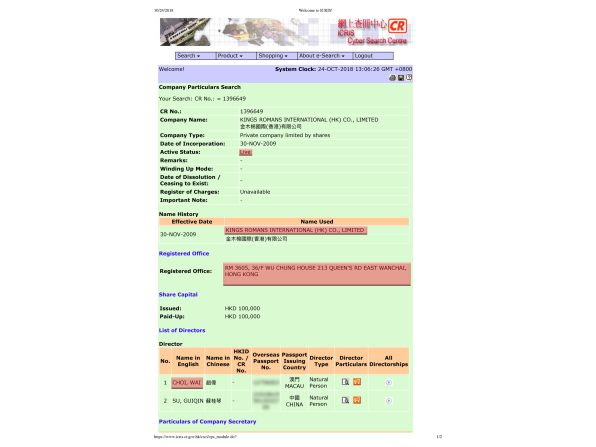

That cog is a company called Kings Romans International (HK) Co., Limited. It and Zhao were both sanctioned by the Treasury Department in January of this year.

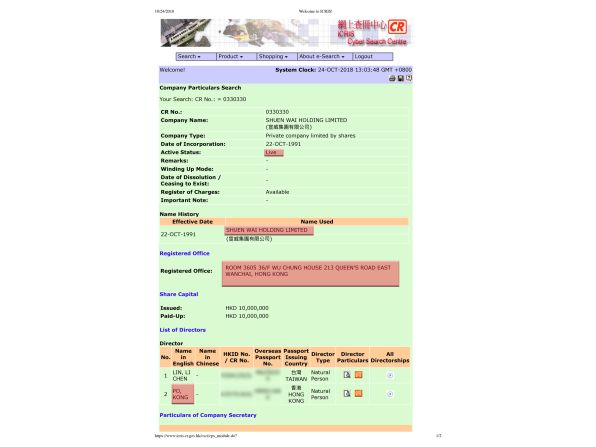

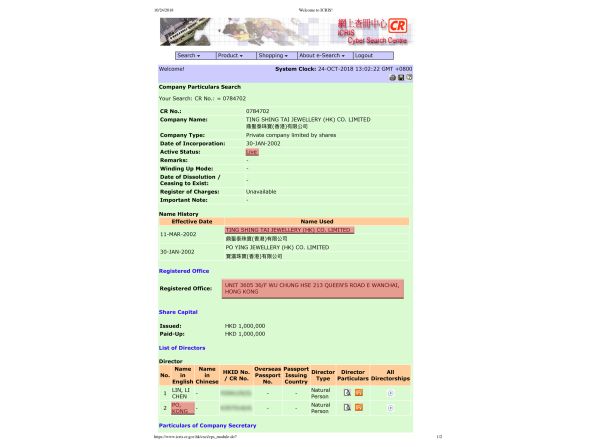

According to records from the US Treasury Department and the Hong Kong Corporate Registry, the business is housed in a spartan office tower called Wu Chung House nestled in a commercial part of the city’s busy Wan Chai district, a fast gentrifying red light district still famous for its seedy bars.

The Treasury did not specify what exactly goes on in the office. Hong Kong, however, maintains a reputation as a notorious hub for moving dirty money, with authorities in the city openly acknowledging the problem.

“Our competitive advantages here – namely, free flows of capital, people, goods and information; well established legal system; sophisticated market infrastructure; and advanced professional services – also make our market attractive for criminals seeking to hide or move funds or evade financial sanctions,” Arthur Yuen, the deputy chief executive of the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA), said in April, during a speech at a conference sponsored by the Association of Certified Anti Money Laundering Specialists.

The Kings Romans office is supposed to be located at the end of a dimly lit hallway on the 36th floor of Wu Chung House, according to public records, but there was no sign of it when CNN visited.

The building’s directory shows that a company called Shuen Wai Holding Limited uses the office space. Real estate records confirm that Shuen Wai is the property’s owner.

Shuen Wai and Kings Romans share more than just an address, however. Shuen Wai and one of its two company directors were sanctioned by the US Treasury Department in 2008 amid allegations that the office was a key part of the financial network used by the UWSA to launder profits from drug sales.

“It makes total sense that the UWSA would be operating out of Hong Kong. They have a long history of mixing illicit with legal activities … and Hong Kong is the perfect place to do that for them,” said Evan Rees, an analyst at the intelligence firm Stratfor.

Companies in Hong Kong sanctioned for drug ties

Down the dark hallway at the office’s entrance, Shuen Wai is the only business that’s visible. Its name is displayed in shiny block letters above an empty secretary’s desk. It was decorated with ornate wooden sculptures and marble floors, but with half the lights off and no one in sight.

The fact that the business was highly visible was a surprise to some of the sanctions experts CNN spoke with about the case.

“They usually at least make an effort to repaint the sign, even if it is the same address and same cast of characters in front of you,” said Peter Harrell, a sanctions expert at the Center for New American Security who previously served as deputy assistant secretary for counter threat finance and sanctions in the State Department’s Bureau of Economic and Business Affairs.

“Operating 10 years without changing the name, that’s pretty brazen.”

When CNN rang the doorbell at the office, a middle-aged, bespectacled man answered. He said the company was previously involved in the jade trade but now works in funeral services.

He refused to give CNN his name, but said he had been an account manager at the company for 20 years, during which time he has known the two individuals currently listed as Shuen Wai’s co-directors. He said the duo are based in mainland China and only come to Hong Kong a few times a year, a couple days at a time. He agreed to pass on a message to them from CNN – which they did not respond to – and then retreated back into the office. When CNN called back a couple days later, the individual said the couple was not willing to speak to CNN.

When asked about the Wu Chung House connections, the UN’s Douglas stressed that each case is different and the age of a specific holding company was not something he could comment on.

“That said, if the holding company has been a front for drug trafficking for 10 years it is pretty serious and concerning, and authorities should be investigating,” said Douglas.

“If links are found and organized crime activities are confirmed then there should be some serious actions taken, and questions will need to be asked about how a front company has been able to run for so long in the open in Hong Kong.”

Hong Kong authorities declined to comment when asked about the case.

CNN’s Yong Xiong, Chermaine Lee and Sean Walker and contributed reporting