Last weekend a group of archaeologists unearthed a skeleton they think belongs to the man who presided over the first representative government assembly in the Western Hemisphere.

Now, they have to prove it’s really him.

Archaeologists in Jamestown, Virginia – North America’s first permanent British settlement – began excavating the site almost two years ago. After many months of work, they spent this weekend uncovering what could be the grave of Sir George Yeardley, one of Jamestown’s early leaders.

James Horn, president of the Jamestown Rediscovery Foundation, is confident this is the man they think it is. Based on what they know, he said he’d be shocked if it wasn’t.

“I’d say about 90% confident,” Horn said. “We want to be at 99.9%.”

How they found the buried bones

In November 2016, the experts started excavating the site of a 1617 church, unearthing parts of its original flooring and foundations.

After about a year of work, they discovered the first signs of what looked like a grave shaft in the church’s middle aisle, said David Givens, Jamestown Rediscovery’s archaeology director.

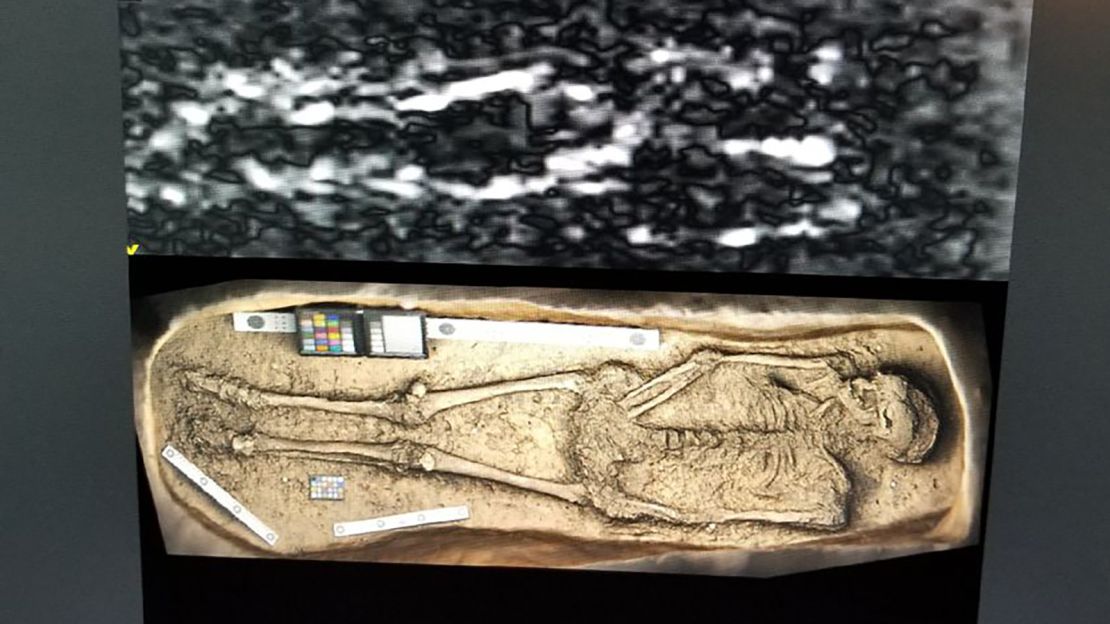

In June, they used ground-penetrating radar to tell researchers what was below the surface without disrupting it, Givens said. In this case, the signals gave them a clear outline of the person they’d soon dig up.

Since then, they’ve been excavating the rest of the remains. They spent the weekend working 15- or 16-hour days in full-body suits – “belted and braced,” archaeo-geneticist Turi King said – to make sure they didn’t contaminate any of the artifacts.

“It’s a forensic crime scene. It’s not easy work,” Givens said.

Putting the pieces together

The skeleton the archaeologists found was in almost perfect condition, Horn said. But one thing was missing: the skull.

Luckily, the archaeologists found a saving grace in the grave: 10 teeth, which are gold mines in learning about the diet and health of the person they belonged to. Each tooth is a data recorder, Givens said. They hold DNA, and plaque can show what foods a person ate.

The bones the researchers found were also important tools. They’re reliable age markers, and they showed this man was around 40 years old, Givens said. Yeardley died in 1627 at age 40.

Other clues came from the grave’s position in the church’s central aisle. This place would have been reserved for a prestigious person, and Yeardley fit that description in Jamestown.

Another clue: An elaborate tombstone commemorating knighthood was found at the site over a century earlier. Yeardley was knighted in 1618.

All the pieces were convincing, but the experts still wanted to find the head.

Then they remembered something. They’d found another grave last fall that contained a skull but no skeleton. So they put it all together – the teeth, the skull and the rest of the new skeleton – and everything “fit like a glove,” Givens said.

Science confirmed it – all the pieces came from the same person’s body, Horn said. Their next step: identification.

How they’ll confirm it’s Yeardley – or not

All signs seem to point to Yeardley, but officials wanted to be certain. Two parallel investigations – one at the FBI and the other at Britain’s University of Leicester – will take place to confirm the results.

With the help of King, a professor at the university, they’ll also use genealogy to track down any living descendants and match their DNA to the DNA they’ve collected from the remains. She’s been in a similar situation; she helped identify King Richard III’s remains in 2012.

“This places him in a giant family tree,” she said. “It’s nice to make it a bit more personal.”

King will compare DNA from the remains to living relatives through an all-male or all-female line. At the same time, scientists will run tests on the skeleton to figure out where the person came from. Dental specialists will look into the man’s teeth. Technology will be used to try to create a facial reconstruction.

The group hopes to reach definitive conclusions on his identity by mid-2019.

“There’s always a chance it’s somebody else. But we’re building a case,” Givens said.

How Yeardley got to Jamestown

Yeardley’s story started across the Atlantic in London, where he was raised before becoming a soldier.

He came from an average family, but once he got to Jamestown in 1610, Yeardley was almost instantly put in power. He helped lead an expedition to discover gold and silver mines, played a key role in a war against the Powhatans and served as deputy governor in 1616.

After going back to England in 1617, he became governor of Virginia in 1618. Yeardley sailed back to Jamestown in 1619.

Once he got there, he implemented a series of reforms from the Virginia Company, which financed the colony. He established a rule of law and a court system, distributed land to settlers and oversaw the creation of a general assembly.

The assembly met for the first time in July 1619 at the site of the current excavation.

“It was the beginnings of our democratic experiments in this country,” Horn said. “1619 is one of the most important years in our history.”

Remembering Yeardley’s – and Jamestown’s – legacies

Yeardley made history in more ways than one. He was one of the New World’s first leaders, but he was also one of America’s first slaveholders.

The scientists’ recent discovery comes a year before the 400th anniversary of two things: the meeting of the first assembly and the arrival of the first enslaved Africans on American soil.

The two firsts – which happened within weeks of each other – mark two very different legacies in the United States. And with their recent findings, Horn said, the experts hope to find out even more about the past and how it shaped the present.

“Archaeology brings history to life,” Horn said.