The young Russian gun enthusiast was struggling. Maria Butina had twice applied for visas to attend the National Rifle Association’s glitzy annual meeting. But she said she was twice denied.

Then, in 2013, the NRA came to Moscow and met her fledgling Russian gun rights group. Soon after, Butina was headed to the United States, visa in hand.

“I want you to go work with the US, not go on a tourist trip,” a Russian oligarch who funded at least one of her trips told her, according to US prosecutors.

By the summer of 2016, Butina was settled in the United States on a long-term visa, making her way in US political circles during one of the most contentious elections in recent American history – while allegedly working with the Russian government.

Her partner: Paul Erickson, an ambitious conservative political operative from South Dakota who once did public relations for John Wayne Bobbitt, produced a movie about a Soviet soldier with former lobbyist Jack Abramoff and had regular cash flow problems.

Whether Butina duped Erickson or drew him willingly into a spy operation is now part of an unfolding Washington drama fit for Hollywood.

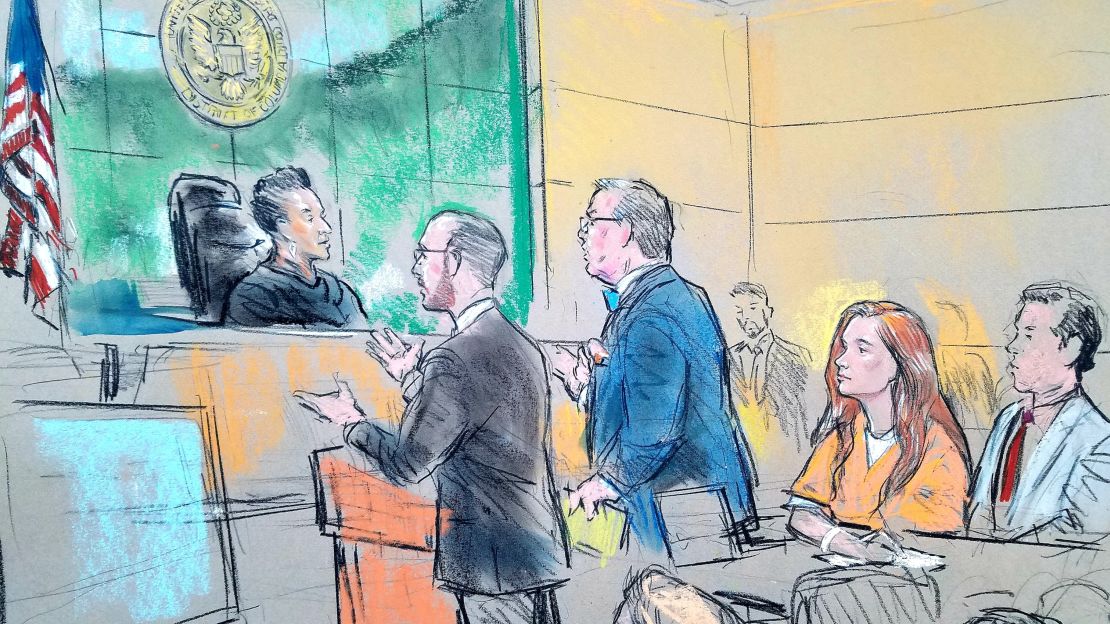

Butina, a 29-year-old flame-haired Russian who once posed with guns in Russian GQ magazine, pleaded not guilty this week to charges she acted as a covert Russian agent working with a Kremlin-connected banker to spread influence in the US. Prosecutors allege she conspired with a Russian official, who CNN has learned is Alexander Torshin, in a plan spanning several years that “was calculated, patient, and directed by the Russian Official.”

The charges appear to be part of a wide-ranging Russian attempt to influence US politics ahead of the 2016 election. The efforts have included Russian intelligence officers’ hacking of Democrats and a years-long social media campaign to influence American voters to favor presidential candidate Donald Trump, according to indictments filed by special counsel Robert Mueller. Over two dozen Russians have been charged. (Prosecutors have not provided any evidence of a direct link between Butina and the Trump campaign.)

Butina’s cover story, authorities allege, was to use a student visa to attend American University in Washington, DC. She appeared to lay the groundwork for her mission years earlier when she set up a pro-gun rights organization in Russia, putting her in contact with Erickson and other top NRA officials as early as 2013.

She would later use those contacts as her vehicle to infiltrate American politics, attend the National Prayer Breakfast, and rub elbows with politicians and pose a question to Trump at a rally.

RELATED: Russia plans to increase aggression post-World Cup

Erickson has not been identified by prosecutors by name or charged with any wrongdoing, but his activities match those described in court filings as “US Person 1,” who authorities allege “was instrumental in aiding her covert influence operation, despite knowing its connections to Russian Officials.”

Where he falls in the scheme is murky. Authorities allege Erickson had “involvement” in Butina’s efforts to establish a “back channel” line of communication between the Kremlin and the Republican Party through the NRA. In a search of their property, a prosecutor said, they found a note in Erickson’s handwriting titled: “Notes on Maria’s Russian patriots-in-waiting organization.” A second note referred to a Russian spy agency, reading: “How to respond to FSB offer of employment?” The context of the notes is not clear.

Erickson, a Yale University-educated political operative, sought to make a name for himself in Republican politics on the national stage beginning with Ronald Reagan’s campaign in his early 20s. He hustled to make inroads with the presidential campaigns of Mitt Romney and Trump. In his path are lawsuits involving investment schemes and he is now under investigation for fraud by the US attorney’s office in South Dakota.

Prosecutors suggest he may have been manipulated by Butina, a woman half his age.

“She appears to treat that relationship as simply a necessary aspect of her activities,” prosecutors said in court filings, adding she offered sex to someone else in exchange for a position in a special interest organization and complained about living with Erickson.

Adding to the mystery of their relationship, her attorney on Wednesday revealed in court that Butina offered to help prosecutors in South Dakota investigating Erickson as recently as May.

Erickson’s place in the spy drama is surprising to some who know him. Stephen Moore, founder of the Club for Growth, a conservative free-markets advocacy group, where Erickson worked for several months a decade ago, said he hasn’t spoken with him in years but recalls, “He was always a fervent anti-communist, Reagan Cold War warrior.”

Erickson and Butina could not be reached for comment. Butina’s attorney has called the charges overblown and denied Butina is a spy.

Erickson’s path through GOP politics

Erickson grew up in South Dakota and became involved with politics at an early age, according to news accounts. As a 23-year-old, he was treasurer of the College Republican National Committee. Then he wrote a parody routine spoofing Democratic presidential nominee Walter “Fritz” Mondale to create a groundswell to help re-elect Reagan.

That group, known as the “Fritzbusters,” included now-disgraced lobbyist Jack Abramoff, who recounted the tale in his book “Capitol Punishment, The Hard Truth About Washington Corruption From America’s Most Notorious Lobbyist.”

Erickson’s interests diversified as he branched into other business ventures.

He was listed as a producer for Red Scorpion, a 1988 movie about a Soviet solider sent on a mission to infiltrate an African rebel army that was written by Abramoff and his brother Bob.

In the early 1990s, Erickson stepped in as a spokesman for John Wayne Bobbitt, the Virginia man whose wife cut off his penis, to handle a legal and media circus, including a worldwide publicity tour called “Love Hurts.” Erickson reportedly was introduced to Bobbitt by Bob Abramoff.

Jack and Bob Abramoff could not be reached for comment.

Three years later, Erickson started Compass Care, a South Dakota business “to provide comfortable homes for the elderly as well as others in need of attentive care,” according to incorporation records filed with the state.

Over the ensuing years, Erickson dabbled in state and federal political campaigns, including work on the Dakota Accountability Project in 2003 set up to try to defeat Democratic Sen. Tom Daschle, according to news accounts. Erickson was one of roughly 10 advisers used by the Club for Growth to vet candidates around 2004 to help them decide which ones they would back, Moore said.

His passion for politics may not have been enough to pay the bills. Erickson was seeking investors in his elderly care business and in February 2006 approached Brent Bozell, a conservative writer and activist who he knew both socially and through business ventures.

Erickson’s investment pitch was one Bozell couldn’t refuse. He said that if Bozell invested $200,000 in Compass Care he stood to make returns that past investors saw of 50% to 100% of their initial investments in a year, according to a lawsuit filed in federal court in Virginia in 2007.

That year, Bozell demanded payment and Erickson gave him a personal check for his initial investment of $200,000. It bounced. Erickson wired $10,000 but Bozell sued alleging breach of contract. A judge ordered Erickson to pay Bozell $190,000 in February 2008. It is not clear if he has been paid. Bozell and attorneys for both men did not return calls for comment.

Erickson was also active in his community serving on the board of the Institute for Lutheran Theology in 2014. That relationship ended in court as well.

Erickson persuaded Dennis Bielfeldt, the institute’s president, and Bielfeldt’s son to invest in Dignity Medical LLC after receiving a personal guarantee, according to the Rapid City Journal, which cited a 2015 lawsuit filed by the Bielfeldts in South Dakota state court alleging fraud. The Journal reported that one of Erickson’s attorneys withdrew from the case after a check bounced. The Bielfeldts won a $40,874 judgment in 2017, according to public records.

Political operatives who encountered him in recent years described him as gregarious but said he tended to overstate his contacts and abilities. He attempted to make inroads with the Romney campaign as well as the Trump campaign, but he wasn’t particularly successful. His efforts to get involved with the Trump transition team once Trump became the president-elect were rebuffed, according to a person familiar with the situation. At one point he was on the board of the American Conservative Union, the group that organizes the Conservative Political Action Conference – one of Butina’s alleged targets.

From Siberia to hobnobbing with the NRA

Butina’s background couldn’t be more different from Erickson’s.

Born in the remote Siberian town of Barnaul in 1988, Butina has said her father, a hunter, instilled in her and her sister a love of guns.

“For such places like Siberia or forests of Russia, this is a question of survival. Everyone has a gun,” she said in a 2015 interview with a New York radio host.

She has said she studied political science and education at Altai State University in her hometown and earned the Russian equivalent of a master’s degree in 2015.

A self-starter, Butina said she spurned handouts – even from her parents.

“I never liked to take money from my parents, so I began to earn my own money during my first year of university. I was a tourism manager, washed dishes, worked as a manager in a garbage collection company, wrote articles, worked on television, distributed leaflets,” she said in a lecture at a Republican summer camp in Erickson’s home state of South Dakota in 2015. “After graduation, I started my own business in retail, selling furniture.”

Her furniture chain – House & Home, LLC, according to her LinkedIn page – expanded to include seven stores, but Butina couldn’t shake her “dream of being a politician,” as she described it in the South Dakota lecture. She sold her company and moved to Moscow in 2010, at age 22.

Soon thereafter, Butina launched the “Right to Bear Arms,” aimed at easing Russia’s restrictive gun laws. Torshin, the former Russian senator and official at the Central Bank of Russia, became of the highest-profile supporters of the initiative. In 2015, he made Butina his special assistant at the Central Bank.

Butina’s gun rights group offered her an avenue to build deeper connections in the United States.

She reached out to Alan Gottlieb, the founder of the Bellevue, Washington-based Second Amendment Foundation and invited him to speak at a conference fall 2013 conference she was hosting in Moscow, he told CNN. The event featured state-of-the-art acoustics and real-time translation, he said. More than 200 gun rights activists attended.

Erickson’s and Butina’s paths crossed in Moscow in 2013.

David Keene, a board member and former president of the NRA, was going and Erickson joined him on the trip, according to social media posts and Gottlieb.

By her account, that conference paved the way for her visit to the United States, to attend the 2014 NRA Annual Meeting in Indianapolis.

Butina had applied for visas twice before to attend the annual meetings, splashy events that attract tens of thousands of attendees and feature speeches from the NRA’s top brass, US politicians and extensive firearms exhibits, but both applications were denied, according to her personal blog. It wasn’t until NRA leadership visited her on that Moscow trip that she was able to obtain a visa.

Her close ties to Torshin also helped ensure VIP access at the meeting. She later posted a photo alongside a grinning Wayne LaPierre, the NRA’s chief executive.

“After that it was possible to prove that I would not stay in the US, and that I’m going there for business,” she wrote on her blog in Russian. A spokesman for the State Department declined to comment on Butina’s visa applications, citing confidentiality.

Meanwhile, Butina’s relationship with Erickson was quickly evolving beyond a shared interest in gun rights.

By November 2014, the two were discussing Butina’s long-term visa options for coming to the US, including work visas, prosecutors said.

“Conversations on email with her prospective and then-boyfriend about what visa status to apply under are perfectly normal,” Robert Driscoll, Butina’s attorney, said in court Wednesday. “There’s obviously a concern when two people are in a relationship to get the appropriate visa status.”

She ended up traveling to the US on tourist visas frequently.

During a 2015 visit, Erickson brought her to South Dakota to lecture at the Republican summer camp.

She and Torshin became regular fixtures at exclusive NRA events for donors who had given $1 million or more and hospitality suites for lifetime members.

The NRA did not return calls for comment.

The alleged conspiracy takes hold

But Butina’s Russian handlers had been hankering for a more permanent fix, according to prosecutors, and Erickson was there to help.

In February 2016, several months before Butina would come to the US on her student visa, Erickson set up a company with Butina in South Dakota called Bridges LLC. The address on three limited liability companies created by Erickson all link to the same address, an apartment complex in Sioux City, South Dakota.

Erickson said the firm was established in case Butina needed any monetary assistance for her graduate studies, he told McClatchy newspapers.

That same month she and Torshin attended the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington. She also sought to arrange “friendship and dialogue dinners” in New York and Washington and Erickson provided with her a list of people to invite. Butina told another American that she received approval from a representative of the Russian presidential administration “for building this communication channel,” according to an email cited in court papers.

In May 2016, she applied for a student visa, according to prosecutors, and enrolled at American University where she studied at the highly regarded School of International Service.

Strongly opinionated, she was unafraid of making waves with peers and professors in the classroom, according to former classmates.

She vocally defended Russian President Vladimir Putin and other Russian interests, which prompted “very hot conversations,” one former classmate said. She sported a mobile phone case with Putin’s portrait on it and, for a while, her computer had Putin wallpaper set as her desktop background.

She “always had sort of an odd take on things, whatever the topic of discussion might have been,” said Mark Brophy, another classmate at American University.

‘All of her inner circle were men who were 60 and above’

Butina was intensely interested in cybersecurity issues. She co-authored a paper about cybersecurity governance with two American University faculty members. When her insurgency class was assigned a group project to analyze an insurgency movement, she lobbied her group to focus on the international hacking group Anonymous.

“I really only found it odd that she would consider [Anonymous] an insurgency,” said Brophy, who worked with her on the project. “I didn’t know that she was particularly sympathetic or unsympathetic to them, only that she thought they were something of the wave of the future, which I thought was a bit peculiar.”

She later did an internship at the Beijing-based Asia Pacific Top Level Domain Association, according to her LinkedIn page and a colleague she told about the experience. The organization said in a statement it “was approached with a request to arrange an internship for a Russian, Ms. Maria Butina,” but did not say by whom. Butina completed her summer 2017 internship remotely, which included a paper on cybersecurity challenges and a presentation for a conference.

Butina fretted about her finances while in school and told colleagues she had a scholarship that covered her tuition but not her living expenses, according to one person who knew her. In addition to her internship, she held part-time jobs on the American University campus, a university spokesman confirmed.

She settled into life in Washington and a tai chi studio awarded her a scholarship.

Still, her social circle was a bit perplexing to some of her schoolmates.

“All of her inner circle were men who were 60 and above,” one friend, who asked not to be named, told CNN.

When birthday parties or other events were held on Butina’s behalf, they were populated with older men from Capitol Hill and the NRA, said one person familiar with the parties. They were often Russian-themed – at least one was held at Mari Vanna, a cozy Russian restaurant in downtown Washington, where Erickson footed the bill, the friend said.

Butina would also “routinely” ask [US Person 1] to help complete her academic assignments, by editing papers and answering exam questions, prosecutors allege in court filings.

“She was very thankful for Paul,” the friend said, adding that Butina had noted Erickson helped her with her expenses.

“They had a very large age difference,” Butina’s friend said, “but she was very tender with him, hugging him all the time.”

Butina wore her two hats interchangeably. She continued her efforts at Torshin’s direction to make inroads in Republican politics, according to prosecutors. She crossed paths and snapped photos with Rick Santorum.

The former GOP senator says he doesn’t remember Butina.

“It was as much a surprise to you as it was to me that I saw my picture with her,” Santorum, an CNN political commentator, said in an interview Wednesday. “I couldn’t have picked her out of a lineup.”

‘Kremlin connection’

Saul Anuzis, a former chairman of the Michigan Republican Party who runs a political consulting firm, said he has met Butina on roughly three occasions, all conservative political conferences.

“To me she was a novelty because the idea of having someone who was promoting gun rights in the former Soviet Union under Putin was kind of an interesting thing,” Anuzis said. “That was kind of her badge that she carried around and what everyone was interested in.”

In one instance, Torshin aimed to meet with Trump around the 2016 NRA convention in Louisville, Kentucky. The meeting never took place, but Torshin and Butina did cross paths with Donald Trump Jr. at a dinner on the sidelines of the event.

Trump Jr. testified to lawmakers last year that he briefly met Torshin at a dinner with a few dozen officials from the NRA. Trump Jr. said they spoke for only “a few minutes” and did not talk about colluding with the Russian government.

Erickson also approached the Trump campaign. One outreach came in May 2016 when Erickson sent an email to Rick Dearborn, a Trump campaign adviser, with the subject line “Kremlin connection.”

According to a source, the email said Putin wanted to invite Trump to visit the Kremlin before the election. Erickson noted that Russia was quietly seeking a dialogue with the US that it couldn’t have under the current administration and the Kremlin believed the only possibility of a true reset was with a Republican in the White House, according to the source.

Erickson described someone who appeared to be Torshin as Putin’s emissary, the source said.

The emails were first reported by The New York Times.

Torshin encouraged Butina telling her that October, “This is hard to teach. Patience and cold blood + faith in yourself. And everything will definitely turn out,” according to a private message cited in court filings.

On election night, Butina told Torshin, “I’m going to sleep. It’s 3am here. I am ready for further orders,” the court filings allege. Their efforts were rewarded and in February 2017 Torshin, with Butina by his side, attended the National Prayer Breakfast.

The following month US media outlets published articles about Butina and her relationship with Torshin and Erickson. Torshin commented that “you have upstaged Anna Chapman,” a reference to the Russian spy apprehended in a sting known as the “illegals” a decade ago.

By the fall of 2017 Butina was of interest to lawmakers investigating Russia’s interference in the presidential election. She hired a lawyer and in April 2018 sat for eight hours of closed-door testimony with the Senate Intelligence Committee.

FBI raid

On April 25, over a dozen FBI agents wearing tactical gear with guns drawn showed up at Butina’s front door with warrants to search her property, according to her lawyer. A warrant related to the fraud investigation of Erickson was also executed. A thumb drive containing notes written in Russian was picked up.

Amid increased scrutiny, Butina grew despondent. She was being mentioned more frequently in news coverage because of her seemingly bizarre ties to the NRA and her efforts, along with Torshin and Erickson, to try to set up back-channel communications during the campaign between Trump and Putin.

“She was very sad, very squeezed emotionally,” her friend said. “She started avoiding people, less parties, less meetings.”

Butina, who had told classmates she hoped to one day open a consulting firm in Washington, mentioned that all of her dreams were disappearing. She said it was no longer safe for her to return to Russia, either.

In May 2018, Butina graduated with a master’s degree in international relations. But her friend didn’t spot her at graduation or any of the celebrations surrounding their commencement.

A few weeks later her lawyer offered Butina’s assistance to prosecutors investigating Erickson who she was planning to move in with in his apartment in Sioux City. Erickson set up another company in South Dakota called Medora Consulting LLC on June 15, 2018.

With school behind her, Butina started planning her move to Sioux City with the boyfriend she had “expressed disdain,” about living with, according to prosecutors. She applied for a new visa and went with Erickson to a bank in Washington where they were observed sending $3,500 to an account in Russia.

Two days later the couple bought boxes from a U-Haul truck rental facility and discussed renting a moving truck. The next day, FBI agents arrested Butina at her apartment and charged her with conspiracy and acting as a foreign agent in the US.

Betraying little emotion and clad in an orange prison jumpsuit, Butina watched in court Wednesday as a government prosecutor deemed it “absurd” to believe she was nothing more than a recent graduate.

CNN’s Jeremy Herb, Liz Stark, Paul Murphy, Caroline Kelly, Austen Bundy and Katelyn Polantz contributed to this report.