Gideon Wanjohi was arrested in 2015 and sentenced to two years in prison in his hometown in Kirinyaga County in central Kenya.

His crime: not taking his pills.

The year before, Wanjohi was diagnosed with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and immediately prescribed a treatment spanning almost two years.

This level of resistance means the bacteria that cause the infection are resistant to at least two of the most powerful anti-TB drugs, isoniazid and rifampin.

Wanjohi was required to take more than 10 large tablets a day, in addition to daily injections of kanamycin, he said, which made his feet swell until he could no longer walk at times.

The injection in particular was painful, he said, and made him dizzy and nauseated.

The treatment was prescribed for 20 months, but two months in, he stopped taking it at all.

Two weeks after that, he was arrested.

Public health officials arrived at his mother’s home at 7 a.m., just before breakfast.

“They came in a private car and walked straight up to me and ordered me to get into the car,” Wanjohi said. “I knew one of the officers because he was in charge of the drugs at the clinic, but he didn’t even want to say hello.”

Any discussions would happen at the police station, they told him.

“At first, I thought it was a joke until I got to the police station and got locked up,” Wanjohi said.

The 40-year-old construction worker says he was taken to court the following day, charged with interrupting his TB treatment cycle by not taking his drugs, and sentenced to two years in jail.

“I tried to explain to the magistrate,” he said. “But the magistrate insisted that it’s a crime and I should be jailed.”

Kenya’s Public Health Act previously allowed public health officers to take any action necessary, including the detainment or isolation of infectious patients in prison, to prevent the spread of disease and minimize risk to the general public.

It was overturned in 2016, but not before dozens of patients were sent to jail.

Depending on the resistance pattern of the bacteria behind the disease, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, treatment for TB can involve a daily cocktail of drugs including 10 to 15 tablets in addition to an injection for up to 18 to 20 months, according to Dr. Andrew Owuor of the Respiratory and Infectious Disease Unit at Kenyatta National Hospital.

Those choosing not to adhere to the regimen risked being incarcerated and having it forced upon them.

Toxic treatments: Choosing between deafness and death

A recurring – and evolving – infection

This was the third time Wanjohi had been diagnosed with TB.

Infection affects a person’s lungs, resulting in symptoms such as a prolonged cough, chest pain and coughing up blood.

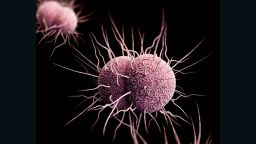

Transmission is through the air from person to person, and infections are typically curable with antibiotics such as isoniazid, rifampin, ethambutol or pyrazinamide.

An estimated 169,000 people were infected with TB in Kenya in 2016, with at least 29,000 dying from the disease, according to the World Health Organization. Globally, 10.4 million people were infected with tuberculosis that year, and approximately 1.7 million died.

Wanjohi first contracted the infection in 1986, when he noticed a persistent cough, chest pains and fever. He was placed on treatment for six months, but two months into it, he felt better and stopped taking the pills.

Four years later, the infection came back, but this time, it also struck his two sisters.

“We were all put on a six-month treatment course. I stopped at the fourth month, but my sisters finished their treatment,” he said.

“I was drinking too much and kept on forgetting to take my drugs, and so I saw no point of taking them anymore.” He had also started feeling better, he said.

When treatment for any bacterial disease is stopped or interrupted, the bacteria can develop resistance against the drugs being used. If the bacteria evolve and infection returns, it can be much harder to treat.

WHO lists Kenya as a high-burden country for multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, one of 30 nations grappling with the disease.

Kenya also features on the high-burden lists for regular tuberculosis and joint TB/HIV cases and deaths. Weakened immunity from an infection with HIV can make people more prone to contracting or developing TB.

Protection through incarceration

In Kenya, standard TB treatment is prescribed for the long-term, but for the multidrug-resistant version, patients must be supervised by a health officer when taking their medication, a requirement under WHO guidelines for the Direct Observed Treatment strategy.

For Wanjohi, this involved visiting Kerugoya Health Centre in Kirinyaga County– approximately 30 miles from home – on a daily basis.

Owuor added that multidrug-resistant TB treatment is a lot more lethal and has many more side effects than treatment for regular TB.

Kanamycin is a painful daily injection that can cause hearing problems, while some of the pills can have psychological effects, such as convulsions, hearing problems and numbness.

“Because MDR-TB treatment is so difficult to take, many patients don’t complete their drug course and don’t get cured. In fact, only about half of them end up TB-free,” Owuor said.

But incomplete treatment can result in increasingly resistant bacteria and the risk of transmission to others, which led Kenya to implement some extreme laws.

Since the 1930s, but especially between 1986 and 2016, TB patients who defaulted on their treatment could be incarcerated because they posed a risk to the general public, according to Sections 17 and 27 of Kenya’s Public Health Act.

“The Public Health Act authorized public health officers to take whatever action they deem necessary – including detaining infectious patients – to prevent the spread of disease,” said Samuel Misoi, assistant director for public health at the National Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Lung Disease Program.

The Public Health Act has been in place since September 1921 and was used to isolate people who had diseases such as leprosy or TB under quarantine or asylum.

It wasn’t until the 1980s, when TB cases began to rise, that patients began being isolated in prisons, according to Misoi.

“In prisons, the patients could not run away, and they had no other option but to take their drugs as prescribed under supervision,” he said.

Misoi says the act was good because it protected innocent people from being infected by TB and ensured that others completed their treatment.

“The TB cases are going up, and people are still dying of the disease, yet it can’t be cured because there is no one to force them to finish their drugs,” Misoi said.

Dr. Solonka Nombaek, head of the Clinical TB Control Unit at the Kajiado County Hospital in the Rift Valley region, said that before the act was nullified in 2016, he sent four patients to prison because they refused to take their medication.

“Would you rather risk the life of many because of one individual or save them?” he asked. “I have many cases of patients defaulting on TB treatment, and I can’t do anything now.”

Nombaek cited a case in which a man got TB and then defaulted on treatment and infected his wife and 4-month-old. His child then died.

“The mother came to hospital, but it was already too late for the child. This is a case where imprisonment was important,” he said.

Life inside

Wanjohi was detained in Kerugoya Prison in central Kenya, a maximum-security facility, from June 2015 to January 2016. He did not finish the two-year sentence because of a presidential pardon on Mashujaa Day (Heroes Day) that allows the release of a set number of petty offenders each October.

He says he shared a cell with 10 other TB patients, and they were otherwise indistinguishable from other inmates who had committed more serious crimes.

“The only difference was that unlike the other prisoners, we were given porridge early in the morning before taking our drugs. Nothing more,” Wanjohi said. Their drugs could not be taken on an empty stomach.

“Everything else was just as the other criminals who were in jail,” he said.

Wanjohi described how he would wake as early as 4 a.m., when all the prisoners woke up, take a cold bath and wait for his porridge at 6 a.m. “As soon as I finished the porridge, I would head straight to the room where the prison warden gave us the drugs. A slight delay or failure meant a thorough beating with the cane,” he said.

“We would then sit and wait for lunch, sit and wait for dinner, then sleep,” he said, adding that his movements were limited to isolation zones.

David King’oo, deputy commissioner of Kenya’s prisons, said that although there was no special treatment for the prisoners, no TB patient was subjected to harassment or mistreatment while in isolation.

He added that waking early is normal for everyone in prison, “but there was no beating.”

“Just like any other prisoner, the patients were to follow the strict rules like taking their drugs on time and doing the right thing at the right time,” King’oo said. “The prisons didn’t have a budget to handle the cases of TB patients, and therefore it was not possible to have a special diet for them.”

After his release in January 2016, Wanjohe found it difficult to pick up his old life.

“No one back at home believed that I was imprisoned for just not taking my TB drugs,” he said. “To date, they still doubt it, which has elicited all sorts of rumors about me in the village.”

Wanjohe has been unemployed since his release and relies on his mother to survive, he said.

Serving more than your times

Elisha Njoroge, 34, from the town of Mwea in central Kenya, was imprisoned for defaulting on his TB treatment in 2015 and served a full two-year sentence.

Njoroge’s father and brother died of TB two and three years before he was sentenced. He said he was diagnosed with multidrug-resistant TB in 2014 and put on a 20-month treatment plan. But nine months in, he was involved in a road accident and soon stopped taking his drugs.

“I lost my memory and forgot to take my drugs for two weeks,” the 34-year old public transport driver said.

“I was then arrested and taken to jail by the health officials, and the magistrate sentenced me to two years in jail for defaulting on my treatment.”

His sentence in Mwea Prison was longer than his remaining treatment term, with the magistrate saying he was to serve more months as discipline, he said. He was released in June 2016.

Njoroge was almost finished with his treatment before he defaulted, and at that time, anyone who defaulted on medication was to be imprisoned for two years, said Franklin Mwenda, a health officer at Kerugoya Medical Center and former health officer in charge of TB in Kirinyaga County.

“Though it is not anywhere in the law, that was the minimal time they were to be in jail, because within two years the patients will have successfully finished their treatment,” Mwenda said.

Mark Ambundo, a medical officer and warden at Mwea Prison, said it had an isolation unit with 20 rooms for patients to be quarantined.

But Wnajohi and Njorage’s reports suggest otherwise, with them claiming that many shared one cell.

Ambundo, who does not believe that patients should be in prison, insists that at no point did patients share a room.

“Their movement was limited because of the risk of their disease,” he said. “Other than taking drugs under supervision, we would ensure that the patients are observing precautionary measures like wearing masks to avoid the spread of the disease to others.”

Challenging the system

In Kapsabet, in the Rift Valley, brothers Daniel Ng’etich and Patrick Kipng’etich were arrested in 2010 and each sentenced to one year in Kapsabet GK prison for defaulting on their TB medication because of the side effects. They argued that they were not fully informed about the full course of treatment due to language barriers and received shorter sentences.

Ng’etich’s wife left him and took their five children while he was inside, he said.

Kipng’etich, who has a wife and two children, lost his job a tea picker. He now sells milk from the one cow he owns.

But unlike Wanjohe and Njorage, the brothers did not have to see out their sentences. They served two months before a human rights group, the Kenya Legal and Ethical Issues Network on HIV and AIDS, secured their early release.

The group challenged the government’s decision to isolate TB patients in prisons on the basis that it was a violation of their constitutional rights, including their right to dignity, freedom of movement and protection from torture, said Lucy Ghati, the network’s HIV/TB program manager.

“Isolating TB patients in prisons is dangerous to the prison population too, as there are no precautions taken to prevent the spread of TB within the prison,” Ghati added.

The group filed a petition against their imprisonment. It used the brothers’ case to challenge the government on two issues: the constitutionality of involuntary confinement as a measure to protect public health and the use of Section 27 of the Public Health Act to confine persons with communicable diseases to a government prison.

Hassan Tari, commandant at Mwea Prison, also believed the patients didn’t belong there.

“These were not criminals, and it was not right for them to be held in prisons. The prisons have no specialized facilities like the hospitals,” he said.

He said that the major concern while patients were in prison was the risk of transmission.

His team raised concerns with the Ministry of Health and urged an alternative to isolating the patients in the prison. “The officials would only give us an explanation that the prison was the only place to isolate the patients, as they would not run away and would be closely supervised,” he said.

The Kenyan High Court declared the practice illegal and unconstitutional on March 24, 2016. The judge ruled that patients were best suited to being cared for in health facilities.

“Not only is such action not sanctioned by the Public Health Act, it is also patently counterproductive,” Justice Mumbi Ngugi said in her ruling.

The court directed the government to develop a TB policy that would abide by international rights.

Ngugi ruled that confinement was justifiable, but not in a penal institution. “It cannot be proper to take anything but a human rights approach to the treatment of persons in the position of the petitioners.”

The judge also found that Kenya’s prisons were ill-equipped to care for TB patients, given that they are overcrowded and poorly ventilated, an environment conducive to the spread of TB.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

WHO’s End TB Strategy states that involuntary isolation of TB patients should be used only as a last resort in extremely rare circumstances and never as a punishment.

Officials at the Ministry of Health say the newly revised National Tuberculosis Isolation Policy has launched and is awaiting implementation.

Misoi, of the National Tuberculosis, Leprosy and Lung Disease Program , explained that TB patients will now be isolated in a manner that respects their human rights.

“The policy will serve the public health purpose of protecting the public while using a patient-centered and rights-based approach to TB prevention, treatment and management.”