It was a fiery end to what was once one of China’s highest-profile space projects.

The Tiangong-1 space lab re-entered Earth’s atmosphere Monday morning, landing in the middle of the South Pacific, China Manned Space Agency said.

“Most parts were burned up in the re-entry process,” it added.

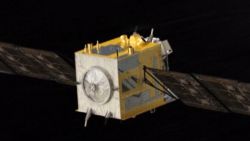

The space lab, its name translating to “Heavenly Palace,” was launched in September 2011 as a prototype for China’s ultimate space goal: a permanent space station is expected to launch around 2022.

Its demise, though ultimately uneventful, captured public attention in recent weeks, as scientists around the world tracked its uncontrolled descent.

“It did exactly what it was expected to do; the predictions, at least the past 24 hours’ ones, were spot on; and as expected it fell somewhere empty and did no damage,” said Jonathan McDowell, an astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

McDowell said there was unlikely to be any amateur images of the vessel’s re-entry, given it was daytime in the Pacific when it crashed to Earth. Scientists had earlier said it might be possible to see the spacecraft burn up in a “series of fireballs streaking across the sky.”

It landed about 8:15 a.m. Beijing time (8:15 p.m. ET Sunday), China’s Manned Space Agency said.

Leroy Chiao, a former US astronaut who flew on four space missions, told CNN he would be “surprised if any major pieces survived the re-entry, as the Tiangong-1 was not that big of a spacecraft as they go, and it did not have a heat shield.”

Anything that did make it through the atmosphere “will be at the bottom of the ocean by now,” he added.

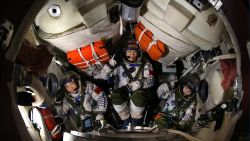

The Tiangong-1 was last used by astronauts in 2013, when a three-strong team spent 12 days on the vessel conducting experiments.

Female astronaut Wang Yaping delivered a lecture from space lab to students back on Earth. During its lifespan, it successfully docked with three spacecraft.

The Chinese government told the United Nations in May 2017 it had “ceased functioning” in March 2016, without saying exactly why.

The uncontrolled re-entry of the space lab has been a blot on China’s space program, as it goes against international best practice.

Chiao said the original plan was to guide the space station down in a controlled manner, “much like the Mir space station was.”

“There’s a specific location in the ocean known as the spacecraft graveyard where nations try and put down into,” he said.

The space lab’s fate hasn’t delayed China’s bold plans. In September 2016, China launched its second space lab, Tiangong-2.

Both vessels are part of the preparation for a permanent Chinese presence in space, which is likely to come into operation just as funding for the International Space Station is expected to end.

China said last week training is underway for astronauts who will use the space station, state news agency Xinhua reported. It said it plans to assemble it in space in 2020 and will become fully operational in 2022.

China also plans to put a man on the moon and send a rover to Mars.

While it’s not uncommon for debris such as satellites or spent rocket stages to fall to Earth, large vessels capable of supporting human life are rarer.

The first US space station, the 74-ton Skylab, fell to Earth in an uncontrolled reentry in 1979. Some debris fell in sparsely populated western Australia, causing no problems except for a $400 fine for littering.

The last space outpost to drop was Russia’s 135-ton Mir station in 2001, which made a controlled landing with most parts breaking up in the atmosphere.

CNN’s Sol Han reported from Hong Kong and Serenitie Wang reported from Beijing. Katie Hunt wrote from Hong Kong