Story highlights

- A study detailing the interstitium raises the idea of calling it an "organ"

- Experts weigh in on this awe-inspiring space in our bodies

(CNN)To be or not to be an organ: That is the question.

Researchers have detailed the structure and distribution of spaces in your body that they say represent a newfound human organ, and this "organ" just might be your body's biggest -- but not all experts are convinced.

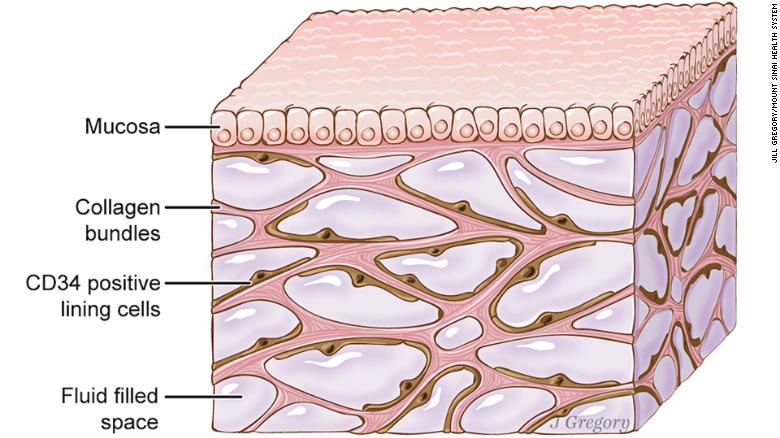

It's the part of the body known as the interstitium, a name for widespread, fluid-filled spaces within and between tissues all over your body, according to a study published in the journal Scientific Reports on Tuesday.

Doctors and scientists have known about interstitial tissue and interstitial fluid, but the study provides fresh insights into a previously unrecognized feature of human anatomy -- and the researchers are raising the idea of calling the interstitium an "organ."

"Initially, we were just thinking it's an interesting tissue, but when you actually delve into how people define organs, it sort of runs around one or two ideas: that it has a unitary structure or that it's a tissue with a unitary structure, or it's a tissue with a unitary function," said Dr. Neil Theise, professor of pathology at NYU Langone Health in New York, who was a co-senior author of the study.

"This has both," he said of the interstitium. "This structure is the same wherever you look at it, and so are the functions that we're starting to elucidate."

Additionally, "I think it's bigger than the skin," he said. The skin, comprising roughly 16% of your body mass, is thought to be your largest organ. As for the interstitium, "my estimate is that 20% of the volume of the body is this, which is equivalent to about 10 liters in a young adult."

'Once you see it, you can't unsee it'

For the study, Theise and his colleagues used a powerful microscope with a technique called confocal laser endomicroscopy to examine and analyze healthy living tissue samples from human bile ducts. The samples were taken from 13 patients undergoing pancreatic surgeries at Mount Sinai Beth Israel in New York.

The samples were infused with a fluorescent liquid, allowing the researchers to see every detail. They wrote in the study that they observed spaces where fluid accumulates. Those spaces appeared to be pre-lymphatic, meaning they appeared to drain into lymph nodes.

Traditionally, when such tissue samples are examined under a microscope, the tissues are dehydrated and look like dense layers, Theise said. So the interstitium could have gone previously unnoticed because it was collapsed due to dehydration.

"Now, it's clear that by looking in the living tissue at the microscopic level with this new confocal laser endomicroscopy ... that space is fully expanded and filled with fluid," he said. "Once you see it, you can't unsee it."

Theise described encountering this new view of the interstitium as a moment of "quiet awe."

More research is needed to better understand the true function of the interstitium, how it impacts other parts of the body and the disagreements over its organ status.

After all, "I would think of this as a new component that is common among a variety of organs, rather than a new organ in and of itself," said Dr. Michael Nathanson, professor of medicine and cell biology and chief of the section of digestive diseases at Yale University School of Medicine, who was not involved in the study.

"It would be analogous to discovering blood vessels for the first time, in that they are in every organ but they aren't an organ themselves," Nathanson said.

"In my opinion, this has the potential to change our understanding of the human body because this 'pre-lymphatic region,' as the authors refer to it, may undergo changes in certain diseases states such as certain types of cancer," he said. "So this now puts us in a position to figure out whether this is an effect or else perhaps part of the cause of such diseases."

Shedding light on how cancer spreads

The new study suggests that interstitium spaces may play a role in helping cancer cells spread around the body, becoming metastatic, Theise said.

"It's been known that when cancer invades this layer, either in the skin or in the viscera, that's when it first becomes able to spread outside the organ of where it arose," he said.

When cancer cells break away from a tumor, they can travel to other parts of the body through the bloodstream or the lymph system, according to the American Cancer Society. Since interstitium spaces might act as conduits, "this raises the possibility that direct sampling of the interstitial fluid could be a diagnostic tool," the researchers wrote.

The interstitium could change the way doctors think about not only cancer but also potentially other diseases and many functions within the body, Theise said.

It's the tissue around arteries that gets squeezed with every pulse of your heart, Theise said. It gets squeezed every time your bladder pushes out urine, and it's the space where tattoo pigment resides.

It's also the space where the tip of the needle goes during acupuncture, which Theise said might hold clues to how that complementary medicine approach might impact the body.

"This discovery is extremely exciting because we've defined novel microanatomy and have laid the groundwork for how this may begin to explain cancer spread, inflammation and scarring of connective tissue. This discovery will open up new research pathways for inflammation and cancer progression," said Dr. Petros Constantinos Benias, co-lead author of the study, a member of the Feinstein Institute and an assistant professor at the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health, in a written statement.

"We are optimistic that with what we learned, we'll soon be able to study and target the interstitial space for diagnosis of disease and perhaps for novel personalized treatments," he said.