Story highlights

"Explaining why a behavior is wrong is the most common form of discipline used across countries," one expert says

Here's where spanking and other forms of corporal punishment in the home are illegal

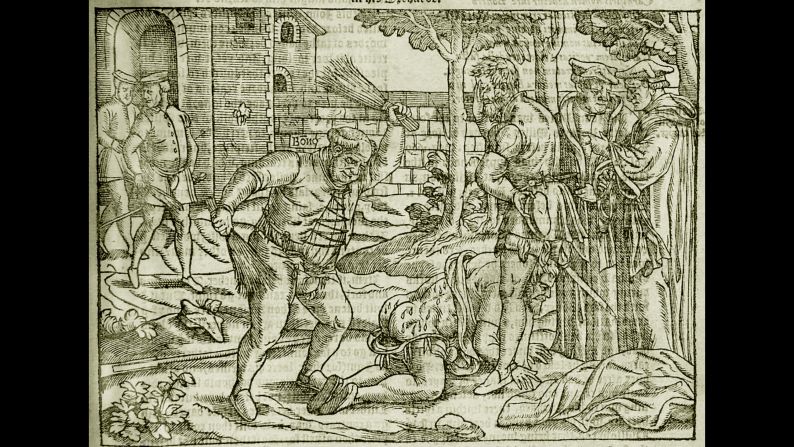

Most parents know the proverb, “spare the rod, spoil the child.”

But in recent years, many have debated whether to practice physical discipline, such as spanking or smacking, in their own homes. To spank or not to spank has become a highly contentious issue.

Many experts have advised against using physical discipline to teach kids lessons. Others argue that the uproar surrounding spanking has been overblown.

Some parents have decided not to spank and view it as harmful to their child’s development, whereas others see no harm in physical discipline and believe it teaches respect.

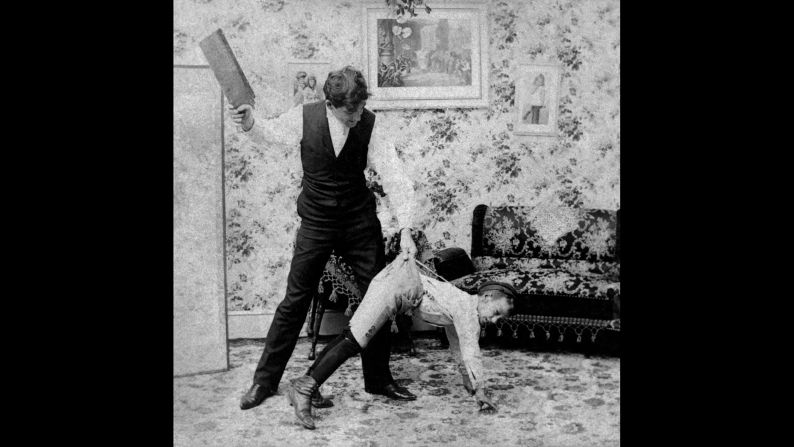

Though there is no clear definition of “spanking” in the scientific literature, the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines the act as “to strike especially on the buttocks with the open hand.”

In some countries, such discipline could land a parent in jail.

Around the world, close to 300 million children aged 2 to 4 receive some type of physical discipline from their parents or caregivers on a regular basis, according to a UNICEF report published in November.

That discipline includes spanking, shaking or hitting the hands or other body parts with an instrument, said Claudia Cappa, a statistics and monitoring specialist at UNICEF and an author of the report.

Overall, simply “explaining why a behavior is wrong is the most common form of discipline used across countries,” Cappa said.

“What was interesting to me as a researcher to see is that parents use a combination of methods, not just one,” she said. “They use violent and nonviolent forms, and they use a combination of physical punishment and psychological aggression,” such as yelling or screaming.

Here’s a look at how children are disciplined around the world, including where spanking is legally allowed and where it isn’t.

In these countries, it’s illegal to spank your kids

Sixty countries, states and territories have adopted legislation that fully prohibits using corporal punishment against children at home, according to both UNICEF and the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

Globally, about 1.1 billion caregivers view physical punishment as necessary to properly raise or educate a child, according to UNICEF.

Some of the countries and territories that have bans are: Albania, Andorra, Argentina, Aruba, Austria, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cape Verde, Congo, Costa Rica, Croatia, Curaçao, Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, Finland, Germany, Greece, Greenland, Honduras, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Kenya, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Mongolia, Montenegro, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nicaragua, Norway, Paraguay, Peru, Pitcairn Islands, Poland, and Portugal.

The other countries and territories that have bans are: Moldova, Romania, San Marino, Slovenia, South Sudan, Spain, St. Maarten, Svalbard and Jan Mayen, Sweden, Macedonia, Togo, Tunisia, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

In the United States, corporal punishment is still lawful in the home in all states, and legal provisions against violence and abuse are not interpreted as prohibiting all corporal punishment, like spanking, according to the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children.

“It’s just in the last 10 years that more countries and a larger set of countries have decided to prohibit corporal punishment,” Cappa said.

“In most of the countries with available data, children from wealthier households are equally likely to experience violent discipline as those from poorer households,” she said, based on UNICEF’s data.

“We tend to think sometimes that only certain categories, particularly socioeconomically deprived households, use violent disciplinary practices, but this is not confirmed by the data on the global level,” even if such differences are seen in some countries, she said.

In 1979, Sweden became the first country to ban the physical punishment of children by law.

Then, “by 1996 only four more states had followed suit,” Anna Henry, director of the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children, wrote in an email.

“Global progress towards prohibition of all corporal punishment of children has accelerated, particularly in recent years,” she wrote. “Since 2006, however, when the World Report on Violence against Children recommended prohibition as a matter of urgency, the number of states banning corporal punishmenthas more than tripled.”

She added that a further 56 states have indicated commitment to achieving a complete legal ban.

There has been a recent move to discourage parents worldwide from spanking or physically punishing their children, led by UNICEF, the Global Initiative to End All Corporal Punishment of Children and other organizations calling for more laws.

“The majority of countries have actually not prohibited corporal punishment, and there are only 9% of children under the age of 5 living in countries where corporal punishment at home is fully prohibited,” said Cappa, who is not involved in the Global Initiative.

In other words, “there are more than 600 million children under the age of 5” in countries where there are no such laws, Cappa said.

A study of six European countries found that the odds of having parents who reported using occasional to frequent corporal punishment were 1.7 times higher in countries where it was legal, controlling for sociodemographic factors.

The study, published in the journal PLOS One in 2015, involved data from Bulgaria, Germany, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Romania and Turkey. At the time of the study, all but two of those countries – Turkey and Lithuania – had legal bans on corporal punishment in the home.

“We also know that legislation is not sufficient when it’s not accompanied by changes in individual attitudes and social norms, and that can even become dangerous, because it can push certain things into a secret sphere,” said Cappa, who was not involved in the study.

Yet not all experts agree that laws should dictate how parents decide to punish their children.

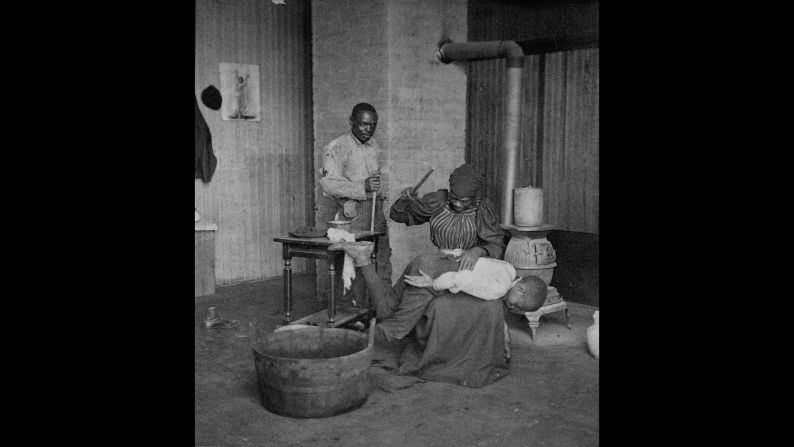

Ashley Frawley, senior lecturer in sociology and social policy at Swansea University in the United Kingdom, said that such laws disproportionally impact marginalized groups – such as the working poor or certain ethnic minorities – regardless of whether incidences of physical punishment actually warrant such surveillance or not.

“This sort of thing happened in Canada and Australia. In Canada where I’m from it was called the ‘Sixties Scoop’ where large numbers of indigenous children were taken from their homes in the [incorrect] belief that indigenous women were not good parents,” said Frawley, who identifies as Ojibwa.

“So I see these smacking bans, which are promoted as awareness raising, as highly suspect,” she said. “There’s a long history in lots of different countries of looking down on parenting styles of the ethnic minorities and working classes.”

Some parents still may prefer to spank their children as, anecdotally, they notice that it might help with more immediate compliance; this preference might also be tied to how they themselves were disciplined or social norms.

What the science says about spanking

Many experts say that spanking is linked with an increased risk of negative outcomes for children – such as aggression, adult mental health problems, and even dating violence – while a few others warn against jumping to such conclusions.

“The clear consensus among experts is that spanking is harmful,” said Andrew Grogan-Kaylor, an associate professor of social work at the University of Michigan, who has researched spanking and child outcomes.

“One plausible explanation is that spanking disrupts the emotional bond between caregiver and child,” he said.

To determine how spanking might have lasting impacts on kids, Grogan-Kaylor and Elizabeth Gershoff, an associate professor at the University of Texas at Austin, analyzed previous studies on spanking published in the past 50 years and involving 160,927 children.

Their meta-analyses found no evidence that spanking was associated with improved child behavior and rather found spanking to be associated with increased risk of 13 detrimental outcomes.

“Across study designs, countries, and age groups, spanking has been linked with detrimental outcomes for children, a fact supported by several key methodologically strong studies that isolate the ability of spanking to predict child outcomes over time,” the researchers wrote.

Their analysis was published in the Journal of Family Psychology in 2016.

Robert Larzelere, a professor in the Department of Human Development and Family Science at Oklahoma State University, disagrees with that analysis.

“Gershoff and her colleagues have yet to identify a single alternative disciplinary tactic in their own research that would significantly reduce behavior problems in children,” he said.

‘Taking away privileges … can be useful’

In a previous meta-analysis, Larzelere dealt with that issue by summarizing 26 studies since 1957 that investigated physical punishment and other alternative disciplinary tactics that parents could use instead.

He found that spanking that was used only as a “back-up” method when other discipline methods were ineffective resulted in either less defiance or less aggression in children when compared with 10 out of 13 disciplinary alternatives, such as reasoning or timeout.

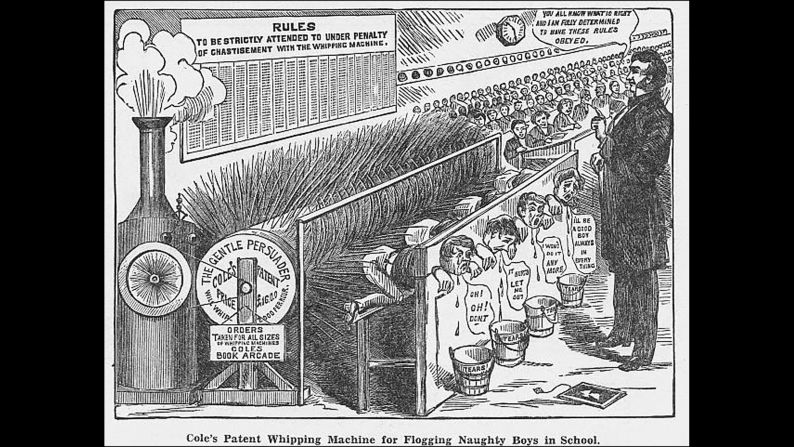

“When used to back-up milder disciplinary tactics consistently, parents are able to phase it out because children learn to cooperate with the milder disciplinary tactics,” Larzelere said. “The only kind of physical punishment that had worse outcomes than alternatives, was if it was used too severely like using an instrument or slapping the face, or if it was the main thing that parents did in disciplining their children.”

That analysis was published in the journal Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review in 2005.

“We have to find the right balance, I think. Children need love and positive parenting … but sometimes they also need effective negative consequences, especially when young children are defiant,” he said. “It’s a complex topic.”

Overall, most pediatricians argue that any form of physical punishment should be avoided, and that there are non-physical ways parents can discipline their children.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends a number of alternatives to spanking, including taking toys and privileges away and the age-old technique of timeout.

The Academy notes that it does not recommend spanking. The American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry also does not support the use of corporal punishment as a method of behavior modification.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

“Before even thinking about discipline, parents need to think about creating a warm, emotionally supportive and loving connection with your children,” Grogan-Kaylor said.

“You need to make clear to your children that you love them, care about their opinions and want to listen to them,” he said.“When discipline is necessary, taking away privileges in a developmentally appropriate manner – so, not too long for the age of the child – can be useful.”