No US president has agreed to sit down with a North Korean leader – until now.

Just by showing up to see Kim Jong Un, Donald Trump would give his murderous dynasty what it has always craved – the prestige and propaganda coup of a meeting of equals with the President of the United States.

That is why the talks represent such a massive gamble for Trump and will subject him to intense pressure to deliver a significant breakthrough in return toward the US goal of dismantling North Korea’s nuclear arsenal.

The difficulty of that assignment is why Trump’s predecessors balked a breakthrough encounter the President has now agreed to.

Because a meeting with the US President is so valuable to the North Koreans, it’s always been the American position that it should be reserved for the moment a deal is on the table – and deliver a significant return.

The White House is convinced that the pain inflicted by its “maximum pressure” sanctions campaign has so weakened North Korea that it is desperate to negotiate.

But Trump’s inexperience and willingness to risk one of his best cards – the prestige of a presidential visit – is one reason some analysts caution he may be walking into a trap.

The stunning developments on North Korea underline one thing: Trump is not like any of his predecessors and cares little for foreign policy orthodoxy.

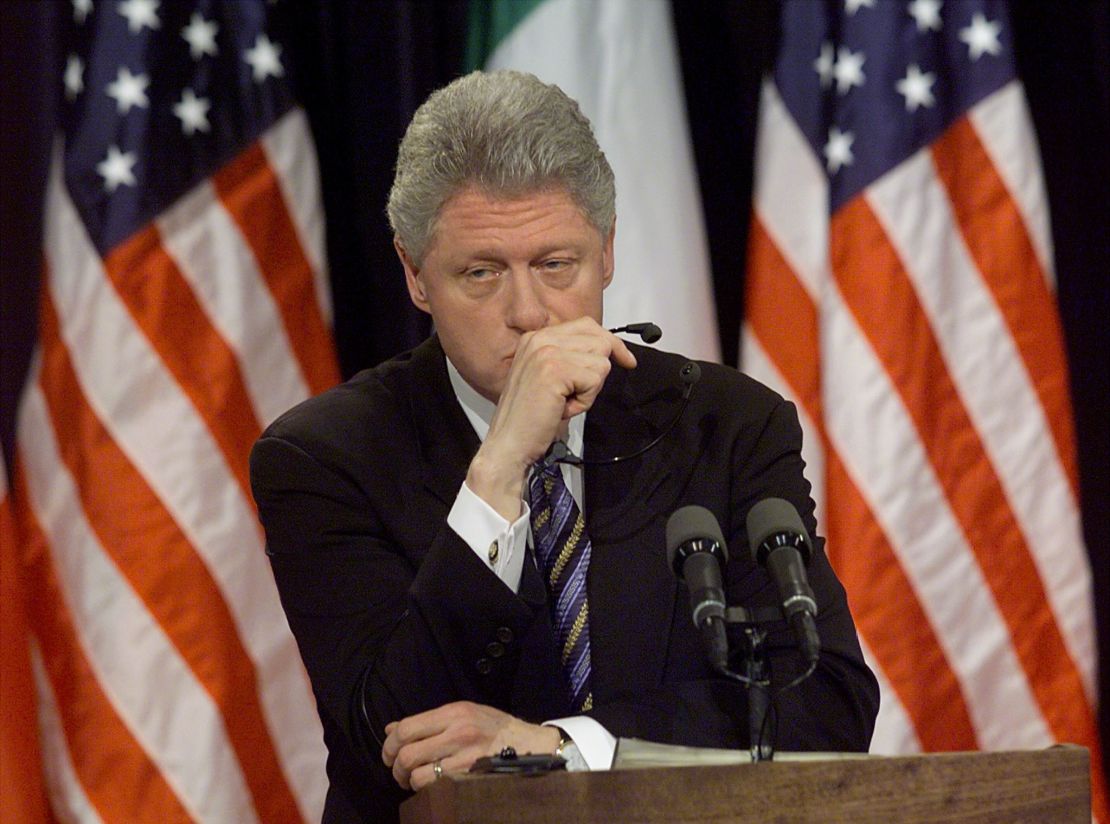

Bill Clinton

Before Trump, the closest a sitting US President got to meeting a North Korean leader was Bill Clinton, who was considering the possibility of traveling to Pyongyang to conclude a missile deal late in his presidency in 2000.

The opening emerged after then-Secretary of State Madeleine Albright visited North Korea and met its then leader Kim Jong Il.

But Clinton, unwilling, unlike Trump, to immediately accept before understanding more about what the meeting could achieve, sent Albright on a reconnaissance mission.

“President Clinton wisely said ‘I am not going until this is prepared, I am sending the secretary … That didn’t thrill them,’ ” Albright said in Brussels on Friday.

Ultimately, after Albright went to Pyongyang and as US diplomats worked to set up the presidential visit, it became clear that North Korea and the US were too far apart on the details of the missile pact to justify handing Kim the huge concession of a Clinton visit.

“Really they were stuck on one issue. North Korea was willing to stop selling missiles and North Korea was even willing to stop making missiles. But North Korea was not willing to give up the missiles it had,” said Jeffrey Lewis, a non-proliferation expert at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.

“North Korea seemed to be holding back their last concession so that they could get the big visit, and the Clinton administration knew that the visit was the big deliverable and they wanted to spend it very carefully,” he said.

George W. Bush

The subsequent Bush administration, including hawks like Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and Vice President Dick Cheney scotched efforts by Colin Powell’s State Department to follow up the Clinton diplomacy.

Then the discovery of a North Korean highly enriched uranium program, that flouted the spirit of an earlier Clinton administration deal to halt North Korea’s plutonium program sent relations back into the deep freeze.

Later on, when Bush did engage North Korea it was in the framework of the six-party talks, including the two Koreas, Japan, the US, Russia and China that was designed specifically to ensure that Pyongyang could not use provocations to secure their goal of direct talks with the US.

Barack Obama

The next President, Barack Obama, came to power vowing to talk directly to America’s enemies. Eventually he traveled to meet Cuba’s President Raul Castro and spoke to Iranian President Hassan Rouhani by phone.

But he concluded it would be wrong to cave to North Korea’s provocations.

“This is the same kind of pattern that we saw his father engage in and his grandfather before that,” said Obama in 2013. “Since I came into office, the one thing I was clear about was, we’re not going to reward this kind of provocative behavior. You don’t get to bang your spoon on the table and somehow you get your way.”

During the Obama administration however there was a sign of just how keen the North Koreans still were to attract prominent US visitors.

In 2009, Clinton finally made it to North Korea for a visit on a mission to free two imprisoned US journalists used by Pyongyang as leverage to lure a significant American to the country.

His poker face in photos alongside Kim Jong Il was seen as a clear attempt to limit the propaganda value of his visit.

Another ex-president, Jimmy Carter, visited in 2010 and returned with another jailed American.

Donald Trump

Not for the first time, Trump has decided to take exactly the opposite tack to Clinton and Obama – and by accepting the invitation he will head onto treacherous diplomatic ground if the visit does come off.

The question before us now is: will Trump’s boldness be rewarded?

Or will he give away what is one of Washington’s best bargaining chips and return home from his talks with Kim with something less significant than a North Korean undertaking to satisfy America’s goal – the verifiable dismantling of its nuclear weapons and intercontinental ballistic missile programs.

His shock move is consistent with his vow to be a disruptive global force and he is showing characteristic bullish confidence that only he can unpick one of the world’s most intractable conflicts.

An optimistic view would be that Trump’s fresh thinking and willingness to give Pyongyang what it wants so quickly is exactly the kind of unorthodox approach that can shake North Korea diplomacy out of its long torpor.