Story highlights

The US is "most dangerous" for kids compared with 19 other wealthy countries, study finds

Infant deaths, car crashes and firearm assaults play a role in America's child mortality rate

The United States has the worst overall child mortality rate compared with those of 19 other wealthy nations in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

That’s according to a study published in the journal Health Affairs on Monday.

The study examined child mortality rates between 1961 and 2010 in the US and comparable nations in the OECD, a group of 35 countries, founded to improve economic development and social well-being around the world. It found that mortality rates were not evenly distributed.

“This study should alarm everyone. The US is the most dangerous of wealthy, democratic countries in the world for children,” said Dr. Ashish Thakrar, lead author of the study and an internal medicine resident at Johns Hopkins Hospital and Health System in Baltimore.

“We were surprised by how far the US has fallen behind other wealthy countries,” he said. “Across all ages and in both sexes, children have been dying more often in the US than in similar countries since the 1980s.”

Some of the factors driving America’s child mortality rate were related to infant deaths, automobile accidents and firearm assaults, according to the study.

Why the US has worst child mortality

Researchers analyzed data on mortality rates for children up to age 19 in the US, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

The data, which dated from 1961 to 2010, came from the Human Mortality Database and the World Health Organization’s Mortality Database.

The researchers found that childhood mortality rates declined gradually from 1961 to 2010 for the US and the 19 other nations, which was a big success for public health. Yet the US rate fell at a slower pace than the other nations over those 50 years.

Specifically, during the decade from 2001 to 2010, the researchers found that the mortality rate in the United States was about 75% higher for infants and about 50% higher for children ages 1 to 19 than the average rate calculated for all of the countries in the study.

During that decade, other countries with infant mortality rates also above the overall average included Switzerland, New Zealand, the Netherlands, Ireland, the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia. Those with child mortality rates above the overall average were Ireland, Austria and Canada.

New Zealand’s child mortality rate was also significantly higher than average, similar to that of the US. Thakrar said the difference in the two nations’ rates was not “statistically meaningful.”

Countries with infant mortality rates below the overall average included Sweden, Spain, Norway, Japan, Iceland and Finland. Those with child mortality rates below the overall average included Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands, Japan, Italy, Iceland, Germany and Denmark.

Overall, for children of all ages between 1961 and 2010, Sweden had the lowest child mortality rate among all of the countries.

As for America, “we found that excess deaths in the US are concentrated among infants, from causes such as immaturity and SIDS, and among teens, from injuries,” Thakrar said.

“Existing research has shown that infants die more frequently in the US, but this was the first time we were able to see that this trend started decades ago. We were also surprised by how much more often US adolescents, in particular boys, are dying from injuries,” he said. “The most disturbing new finding of this study was that a 15- to 19-year-old in the US is 82 times more likely to die from gun violence in the US than in any other wealthy, democratic nation.”

The researchers wrote in the study’s abstract that policy interventions could help to reverse these mortality rates in the US, such as by aiming to reduce the number of automobile accidents, assaults by firearm and infant deaths across the country.

The study had some limitations. For instance, reporting, coding and classifications systems for death counts and cause-of-death data vary across countries. Those systems also have changed over the 50-year period analyzed in the study.

Thakrar added that the study’s data did not include demographic information, so the researchers were unable to examine disparities within US mortality rates.

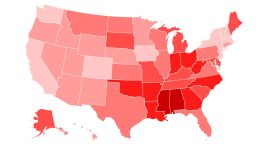

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention released a report last week showing state-by-state and racial disparities in infant mortality rates, with Mississippi having the highest and Massachusetts having the lowest rate from 2013 through 2015.

‘The future of any country is its children’

There are just a few mortality-specific causes that help explain the discrepancies between the US and other countries, said Lindsay Stark, an associate professor of population and family health at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health, who was not involved in the study.

“There were no major differences between the US and other countries in terms of infectious disease or cardiovascular disease, for example. The main reason the US is lagging behind other nations is because of perinatal mortality, including maternal conditions affecting a fetus or newborn, and injuries, mostly due to firearms,” Stark said.

“What these findings clearly show is that there are areas where the US could be preventing child deaths, and we are failing to do so – due to gaps in public policy, a weak social safety net and persisting social disparities that affect families’, mothers’ and children’s health unequally,” she said. “The future of any country is its children, so at a fundamental level, we can see a country’s investment in its future in the way children are surviving and thriving.”

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Thakrar agreed that many of the deaths behind the high mortality rates in the US are preventable.

“To turn around these trends, we will need to think beyond medical care to address the social environment children live in,” Thakrar said. “Every child deserves the opportunity to live a full, healthy and safe life. These findings show that we are not living up to that promise and that we have fallen short of that promise for the last 30 years.”