Cross Platform Link: Versión en español

People on this part of the island knew Quintín Vidal Rolón for two things: his white cowboy hat, which he seemed to wear every day of his 89-year life; and his beat-up Ford pickup truck, which he’d been driving for at least 50 years.

It was in that 1962 truck, and wearing that hat, that Vidal spent his days zipping around the mountainous back roadsof Cayey, Puerto Rico. He sold hardware from the wooden bed of the pickup. And he used those tools, and a lifetime of sweat, to build houses – always in concrete.

Like him, the material was nothing if not consistent. It was strong enough to stand up to a storm, he told clients and family members. Don’t trust anything less durable.

After Hurricane Maria slammed into this US territory on September 20, peeling roofs from wooden homes and amputating branches from trees, the community turned again to Vidal. No one can say exactly how many people survived the storm in the hard-caststructures he helped construct for them, often at little or no cost. But it’s likely hundreds, his family said.

The man who would have been 90 years old in February survived the storm at home alone. Shortly after, he was seen by neighbors clearing debris from roads and flooded houses.

It was the aftermath of the hurricane that would prove fatal.

No one thought much of the lantern at first. Some neighbors noticed the oil-powered flame flickering in Vidal’s living room. He’d started using it after the storm hit – a light he lit at dusk, as the coquí frogs began their chorus. Maria’s winds had toppled power lines like toothpicks in Cayey; and power service in the town, like on much of the island, has been slow to return amid a government response widely described as inadequate. Only 10% of people here have power today, said Mayor Rolando Ortiz. Vidal needed a way to see in the dark.

It was October 20, one month after the storm, when the neighbors smelled smoke.

Daisy Lamboy stood on her roof, straining to find cellular signal to call emergency responders. Margarita León busted through Vidal’s window, releasing a mushroom of heat. It was too late. Vidal’s charred remains were found in a blackened “hellscape,” as one relative described it – a scene so otherworldly, and so seemingly unnecessary, that one firefighter, Vidal’s nephew, fainted.

Several of Vidal’s siblings, children and grandchildren, as well as Cayey’s mayor, the police chief and the director of emergency management – all say Vidal died as a result of the power outages caused by Hurricane Maria, and that have lingered for nearly two months.

If he’d had power, he wouldn’t have been using the lantern with the open flame.

And if he hadn’t used that lantern, he’d still be alive, they said.

In general, “indirect” hurricane deaths – in which a person likely would be alive if not for the storm and its aftermath – should be part of the official death toll, according to Puerto Rico’s Department of Public Safety, which oversees the count. The list of 55 deaths attributed to the hurricane includes ones from heart attacks and suicides that were precipitated by a storm that shook even the sturdiest of the 3.4 million American citizens who live on this Caribbean island.

Yet Vidal’s death – and potentially dozens if not hundreds of others – is yet to be counted by Puerto Rico as it creates a list of mortalities related to the Category 4 storm.

We spent two weeks in Puerto Rico trying to understand why.

The trip included a survey of about half of all funeral homes on the island, which showed the potential for widespread undercounting; interviews with doctors and public officials; and, most importantly, conversations with the family members of Puerto Rico’s uncounted dead.

The analysis of the death toll found problems that start at the time of death and continue beyond the grave.

‘The official count is 55’

When President Donald Trump visited Puerto Rico on October 3, he praised Hurricane Maria’s relatively low death toll – then 16. Officials should be proud of the low number of deaths, and for avoiding a “real catastrophe” like 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, Trump said. Later that day, however, Puerto Rico’s death toll rose to 34.

Since then, politicians, academics and news outlets, including CNN, have raised questions about the accuracy of the official Hurricane Maria death toll in Puerto Rico. A storm as powerful as Maria would be expected to kill hundreds of people, not dozens, said John Mutter, a professor at Columbia University who reviewed deaths after Hurricane Katrina. San Juan Mayor Carmen Yulín Cruz told CNN’s Jake Tapper on November 3 she thought the toll could be 500.

The Puerto Rican government fired back at that estimate.

“In order to support her statement, [Cruz] needs to present the evidence,” Héctor M. Pesquera, secretary of the Department of Public Safety, said in a statement. “If she is not willing to do such, it is an irresponsible comment. The government of Puerto Rico certifies the death count based on factual information in concert with all components involved in the process. At the moment, the official death count is 55.”

To check the accuracy of the Puerto Rican government’s figures, we called nearly every funeral home in Puerto Rico. Funeral home directors are on the front lines of this crisis – they count the dead and they speak with family members about the circumstances. It was through a funeral home director, for instance, that we learned of Vidal’s death and others.

Some funeral homes did not answer our calls, and several declined to provide data. CNN was able to collect responses from 112 of the island’s funeral homes. That’s about half the total number in Puerto Rico, according to Eduardo Cardona, director of the Puerto Rico Association of Funeral Home Directors. (The Puerto Rican Department of Health said it was unable to provide us with a comprehensive list of all funeral homes on the island, saying the computer systems that contain those documents remain down because of the storm).

Those funeral homes identified 499 deaths in the month after the storm – September 20 to October 19 – which they say were related to Hurricane Maria and its aftermath. That’s nine times the official death toll. And, again, it represents only about half of funeral homes.

One funeral home director, José A. Molina, in Vega Alta, was so overwhelmed by work after the storm that he died of a heart attack on October 10, according to his son, Luis Alberto Molina. The 31-year-old said his father was under tremendous stress as he tried to run a sanitary business without reliable power or water service. José Molina had to wait in hourslong lines for fuel, his son said. Before the storm, he had high blood pressure but otherwise was in good health, Luis Alberto Molina said. His color and temperament changed. He stopped eating and sleeping. Eventually he complained of chest pains and was taken to the hospital. His son, who now manages the business, the Vega Alta Memorial Funeral Home, handled his father’s services.

“Me and my siblings are going to continue his legacy,” he said.

We asked the funeral home directors to consult their records before providing these estimates. Yes, they are subjective. All official hurricane deaths in Puerto Rico must be certified by a single office at the Bureauof Forensic Sciences in San Juan, the capital. Funeral home directors are not trained pathologists, and do not conduct autopsies and other tests. They do, however, speak with family members and review death certificates and bodies.

Surveying funeral homes likely underestimates the number of hurricane deaths, said Eric Klinenberg, director of New York University’s Institute for Public Knowledge, who wrote a book that dealt with problems with death tolls following a 1995 heat wave in Chicago.

“The cases where you have the body and the body gets taken to the funeral home almost always understate the real mortality,” he said. “There’s always a significant number of bodies that don’t get processed through funeral homes. What that tells me (is that) there are a lot more cases to be reported – and that number is probably going to spike again.”

The most objective way to estimate the number of hurricane deaths, he said, is to look at how many people died in a normal month in Puerto Rico – and then compare that to the number of deaths during the month of the hurricane. By that measure, 472 more people died in September 2017 than September 2016, according to Puerto Rico’s Demographic Registry.

The Puerto Rican government stands by its count as accurate, based on the factual information it has received to date. Reports from funeral homes and families are simply “rumors,” said Mónica Menéndez, deputy director of the Bureau of Forensic Sciences, which examines deaths to determine if they are hurricane-related.

“There’s no reason for us to be hiding numbers,” she said.

“We work with what we’ve received and we’ve analyzed it. And my personnel work hard to do this. … It hurts us to hear people think we might be playing around with the numbers.”

‘Even the cats prayed for Pilar’

Problems with the Hurricane Maria tally begin as soon as deaths occur.

Hospitals and doctors often are the first line of defense. These medical professionals sign death certificates and, in many cases, decide whether the death is sent to the Bureau of Forensic Sciences in San Juan for investigation. A death must be reviewed by that office to be counted.

Of the 1,968 total deathsreported to us by funeral homes – 499 of which they claimed were hurricane-related – 601 deaths, they said, were sent to the forensics lab for analysis. The Puerto Rican government received a total of 843 deaths for analysis in the first month after the storm, according to Menéndez, from the forensics bureau; of those, 377 were visually examined but not autopsied, she said, because the deaths resulted from natural causes.

Five cases are pending final review, Menéndez said.

In Corozal, an interior municipality northwest of Vidal’s house fire, Pilar Guzmán Ríos’ doctor declared her death natural – and therefore not subject to forensic review – without seeing her body. He did so, he told us in an interview, because it was nearly impossible to reach her house by road at the time. And he wanted her grieving family to be able to move on.

If her body had been sent to the forensics office, Dr. Francisco Berio said, then it could have been subjected to review for days or weeks. If her death was natural, the family could bury her now. He signed her death certificate on September 29. Cause of death: cardiac arrest.

The truth is sadder and more complex.

Guzmán was a veritable force in her mountaintop community. Her booming voice echoed through the hills. She’d scream “¡Hola, chica!” at complete strangers and run to greet them. Her kisses smacked so hard, according to relatives, they left ears ringing. She kept three parrots on her back patio – Paulina, Cuqui and Blanqui – and she taught them to sing “La Cucaracha” and chant the rosary, making them just as boisterous and devout as she was. She learned to drive late in life, but once she had a driver’s license, neighbors started calling her the “town taxi” and the “town ambulance” because she gave so many free lifts.

The morning of her death, Guzmán’s sister-in-law, Madeline Berríos, walked into Pilar’s home to find her three parrots “completely silent” for the first time she can recall. She knew then what she would find next: Pilar’s lifeless body resting on a bed beneath an image of Jesus.

Her family saw it coming because of the conditions of the storm. The vibrant, joyful woman suffered from a number of health issues, and she needed an electric-powered machine to help her breathe through the night as well as refrigeration to safely store the insulin she took to manage diabetes. Without either, said Yaitza Nieves, a nurse who also is Pilar’s grandniece, and other family members, her lips started turning blue. She became weak and dizzy, unable to hold silverware. She couldn’t feed or bathe herself. She started mumbling incoherently.

“Even the cats prayed for Pilar,” a cousin said.

Family members said they called 911 repeatedly and were told an ambulance would arrive to get the woman who normally would have driven a person in this situation to the hospital.

“The death of my sister is related to the Hurricane María because we had no power or running water,” said Paula Guzmán Ríos, Pilar’s sister, who is still living in a shelter without water or power because her roof was torn off and she lives on a hillside vulnerable to landslides. “And, besides that, calls for an ambulance were made – and the ambulance never arrived.”

‘We’ve run out of tears’

Her family didn’t know it, but if Pilar Guzmán’s death had been counted as part of the official Hurricane Maria tally, they might have been eligible for federal aid. A program run by the US Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA, helps families pay for funeral expenses if they can prove their relative died in the storm. The maximum is $6,000; but the deaths must be certified as hurricane-related in order to qualify, according to a FEMA spokesman.

This is just one way the accuracy of the death toll has tangible consequences.

If the world has the impression that the death toll in Puerto Rico is low – as Trump highlighted in his October 3 press conference – then donations and public assistance are less likely to flow toward Puerto Rico, said Klinenberg, the sociologist at New York University.

“One reason it matters is because there’s a question of how bad the situation is – and how many resources are required to help,” he said by phone. “Is it still an emergency, or is the emergency over?” When the public hears that relatively few people died then they get the message: ‘Everyone relax and the local government can handle this.’

“If people are dying every week, that sends a very different message,” he said.

The US government’s response to the hurricane in Puerto Rico has been widely panned as slow and inadequate. One month after the storm, about 1 million of the island’s residents were without running water, and some 3 million didn’t have electricity, according to Puerto Rican government estimates.

The island had a weak power grid and bad roads before the hurricane hit, and conditions are improving. Nearly two months after the hurricane’s landfall, however, progress remains spotty.

Several relatives of Pilar Guzmán, for example, are still living in an elementary school. They collect rainwater from the roof and power a small battery with a car engine. It runs a single light and charges a few cellular phones, which can’t get a signal most of the time.

The mayor of their town, Sergio L. Torres Torres, says deaths will continue if conditions don’t improve. He disputes the Puerto Rican government’s claim no one died here.

“I know for a fact there are deaths that resulted from the storm,” he said.

Experts tell us knowing how, where and why people died could help protect the public in future disasters.

Meanwhile, families of the dead say their loved ones are being forgotten.

When we met relatives of Quintín Vidal, for example, the man who died in the house fire, his granddaughter, Lisandra Llera Vidal, thanked us for coming to talk about a death she thinks the US and Puerto Rican governments want ignored. “You are going to be our eyes and ears to the world,” she said.

“We’ve run out of tears.”

The Puerto Rican forensics bureau says his case is pending toxicological review to help determine whether his death was caused by the hurricane.

‘Potentially problematic’

Anecdotally, two threads ran through the uncounted deaths reported to us by funeral homes: People seem to have died primarily in the aftermath of the hurricane, rather than the storm itself; and many of the victims seem to be older people.

We were unable to document any so-called “direct” hurricane deaths – such as those suffered from blunt trauma or injury – that occurred the day of the storm and were missed by the government. People who may have suffered deaths indirectly related to the storm – those who died awaiting medical treatment, who committed suicide in the aftermath of Maria, or who perished due to lack of power and clean water – were easier to identify.

Some of the undercounting appears to result from confusion about what should classify as a hurricane death. The Puerto Rican government says indirect deaths do count. On its official list, there are three suicides and a few heart attacks, for example. One official hurricane death occurred after a person fell off the roof while apparently trying to repair a storm-damaged home.

Not everyone knows which types of deaths should be counted, however.

In Arecibo, a coastal municipality west of San Juan, CNN previously reported on the death of Isabel Rivera González, 80. Her family believes she died awaiting a medical procedure in a hospital that didn’t have power because of the storm. The Manatí Medical Center, where she was treated, confirmed the power outage but said it did not contribute to her death. Rivera had been a patient of the hospital before and had a pre-existing heart condition, they said.

José S. Rosado, executive director of the medical center, said in October that no deaths from that hospital had been sent to San Juan for forensic analysis. Only blunt trauma, drownings, falls, crime scene victims and bodies that are found dead on arrival, among others, should be sent to the capital for analysis, he said. That appears to conflict with the Puerto Rican government’s definition, which includes indirect hurricane deaths such asheart attacks.

“They were all natural causes of death,” Rosado said.

The Puerto Rican government distributed Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines to hospitals on when deaths should be sent to the forensics lab. The Manatí Medical Center maintains it has followed those guidelines in deciding which deaths to send.

There are few legal requirements, however, on which deaths must be sent for analysis.

Types of deaths that must go to San Juan for review include crime victims, poisonings, suicides, accidental deaths, cremations, nursing home deaths and children’s deaths, among others, according to a 2017 law that established new guidelines for forensics.

Some states have medical examiners or coroners stationed locally to ensure deaths are counted and identified consistently, said Dr. Gregory J. Davis, a professor and director of the University of Kentucky’s Forensic Pathology Consultation Service. In Puerto Rico, only one office classifies these deaths, frequently leaving doctors and hospitals to decide which bodies are analyzed. That is “potentially problematic,” Davis said, because some hospitals might have an incentive not to report deaths that occurred during power outages or other dangerous situations.

“On the other hand,” he said by email, “not reporting could open them up to legal liability.”

‘The disaster is about our failure to act’

Politics also could sway the process.

Puerto Rico’s Institute of Forensic Sciences was formed in 1985 in response to concerns of political corruption in the investigation process, according to the text of the 1985 law.

The institute was initially intended to be an independent research body, beyond the sway of politics. But a 2017 law changed the name of the office to the Bureau of Forensic Sciences and put it under the control of the newly created Public Safety Department.

The secretary of public safety is named by Puerto Rico’s elected governor.

Pesquera, the secretary of public safety, told CNN in October that any insinuation of political meddling in the death toll is “horseshit.” “You think I care what the government of the United States thinks about the body count? I don’t care,” he said. “I could care less what’s less embarrassing.” He’d rather see more deaths included than excluded, he said.

“There is no reason whatsoever for us not to include an accurate count.”

As unsafe conditions continue weeks after the storm, however, said Klinenberg, the NYU professor, more of the blame will fall on the government and its response.

“That’s not natural” to have people dying without electricity weeks after the hurricane, he said. “That’s not about the weather. That’s a story of political negligence. Of course, it’s related to Maria if you can’t get to the hospital because the roads are closed down or you have a waterborne illness because the water is dirty. There are all kinds of mental illness problems that come up because of things like this. These are all directly or indirectly related to the disaster.

“At this point, the disaster is about our failure to act as much as anything else.”

‘The water is coming!’

The forensics office maintains many bodies were never sent to them for review.

CNN, however, looked into two particular cases of possible hurricane deaths that were sent to the forensics office but have not, as yet, been included on the official death toll of 55.

One was Quintín Vidal, the fire victim who died October 20.

The forensics office told CNN its pathologists are still conducting a toxicological review and have not decided whether to declare the death as hurricane-related.

The other was Juan B. Robles Díaz, who hanged himself on September 27.

The forensics office maintains the suicide was unrelated to the hurricane. Robles had been diagnosed with skin cancer months before. Carlos Robles, his son, however, told us his 70-year-old father had been in relatively good spirits following a round of cancer treatment in the United States.

That changed after the hurricane, he said.

For several nights after Hurricane Maria wrecked his Canóvanas home here in the valley below the mountain rainforest in eastern Puerto Rico, a place where horses roam the streets and some homes still don’t have roofs, the elder Robles woke up in the night frantic and screaming.

“The water is coming! It’s flooding!” he yelled, according to his son.

On September 20, the storm brought about 8 feet of water into the family’s pink concrete house, which Juan Robles had lived in for decades, according to Carlos Robles. Water rushed through doors and windows and spewed out of the toilet. Panicked, the family smashed a window in a bedroom in the back of the house to escape. Thirteen of them waded through a rush of stomach-deep water and cut through a fence to seek higher ground.

“I thought we were going to drown,” said Carlos Robles, 47.

Juan Robles survived that day, but the man who used to sit on his porch teasing the runners who passed by, and who never shied away from a fight, never was the same.

After Hurricane Maria, he awoke with night terrors, fearing another hurricane loomed, Carlos Robles said. He ran down the street yelling at the top of his lungs. The house was all but unlivable, but Juan Robles insisted on staying there to protect it. During the day, he positioned a couch by the window so that he could watch for the moment the water would return, his son said.

Seven days after the storm, Juan Robles hanged himself in the bedroom closet.

His 18-year-old grandson found him there, Carlos Robles said.

Workers at the funeral home that identified Juan Robles’s death to us as potentially hurricane-related find it astounding that Puerto Rico would not include his death in its tally.

“How is it possible that this man is not on that list?” said Miriam Vélez de Nieves, who works at the Frankie Memorial Funeral Home in Río Grande. “I don’t know how to explain it.”

Carlos Robles believes his father’s death was a consequence of Hurricane Maria, too.

He told CNN that investigators from the forensics office interviewed him after he identified the body. That interview lasted 30 minutes, he said, and included no questions about the hurricane. Some of the context came up, he said, but no one asked about it directly.

A forensic investigator told us interviews typically last closer to 1 hour and 45 minutes.

Half-hour interviews are “highly unusual,” the investigator said.

The forensics office said there is no mandated time frame for a forensic interview. The office did not respond to repeat requests for autopsy reports and related documentation.

Pesquera did say his office is open to adding to the official death count, however.

In response to CNN’s questions about 71-year-old José Rafael Sánchez Román, whose family says he died of a heart attack or stroke during the storm’s impact, Pesquera told us his office was unaware of the case but would investigate further. If the medical crisis was caused by the shock of the storm, and help wasn’t available, such a death could be counted, he said.

Pesquera told CNN there’s no deadline for a death to be reviewed as part of the Hurricane Maria death toll. Forensics examinations could be reopened even after a person had been buried, he said.

The Puerto Rican government helped set up a phone line to collect tips from funeral homes about hurricane-related deaths and went into the field to investigate reports, said Menéndez, the deputy director of the Bureau of Forensic Sciences. “We went to cemeteries, we went to funeral homes, and it was not as they said,” she told CNN. “We did do that part and we did work together. The thing is, once again, it’s rumors. So, how far do we keep on going? … That’s not my responsibility to go out and verify (reports of hurricane-related deaths), but we took it upon ourselves to verify these rumors.”

In the future, Pesquera said, death certificates in Puerto Rico should be updated so that there is a clear place for doctors to mark whether or not a death may have been related to a storm or other natural disaster.

‘More people are going to die’

Our last stop in Puerto Rico was to meet with Quintín Vidal’s family in Cayey.

There, on November 15, a dozen family members sat in folding chairs in his granddaughter’s living room, which is one of the few homes in the area with power service.

Two public officials in the municipality say Vidal’s death is a sign of federal and Puerto Rican government incompetence. If power service had been restored more quickly, they said, he wouldn’t have died in the October 20 fire. It’s far too easy to dismiss the deaths of older people, assuming they would die soon anyway, said Jesús Martínez, Cayey’s director of emergency management. Doing so ignores the urgency of the humanitarian crisis.

“More people are going to die if we continue to be off the grid,” he said.

The Puerto Rican and federal governments are creating the false impression that the emergency is over, said Cayey Mayor Rolando Ortiz. “They just want to have a good story,” he said, “to make things look positive for them.” The reality, he said, is deaths continue – and they’re largely unacknowledged or they’re slow to be reported by Puerto Rico.

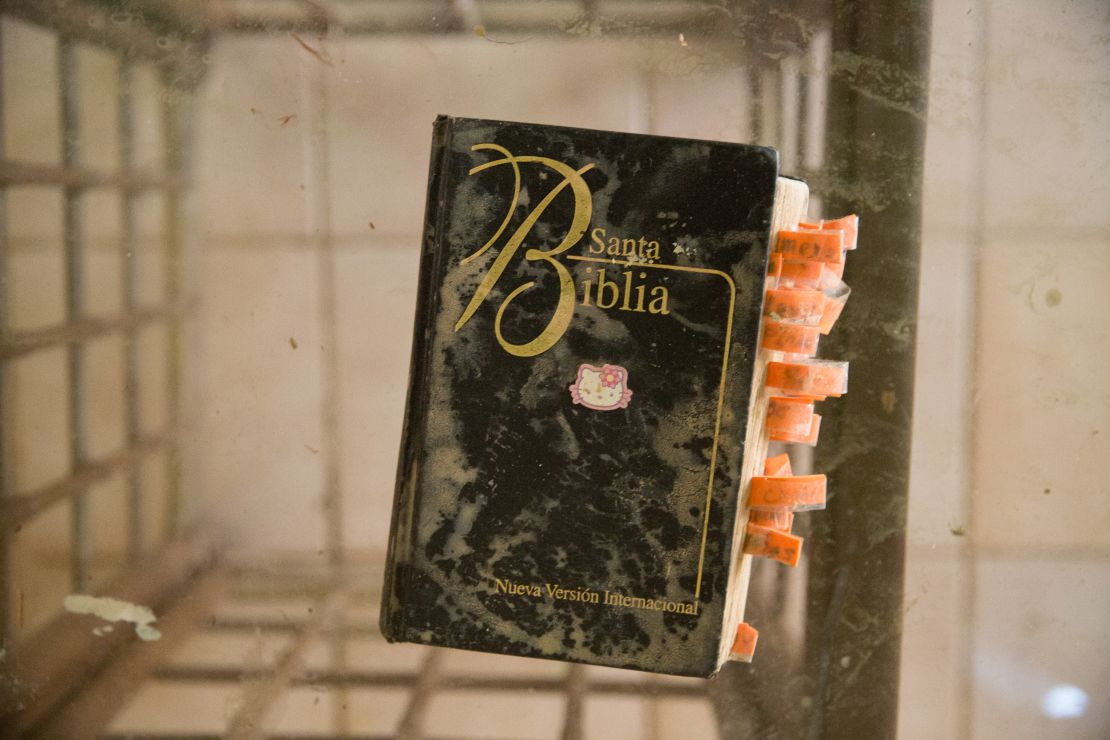

On a table in the family’s home were several framed photographs of Vidal. In one, taken in May this year, he’s shown in his characteristic white hat, blue shirt and khakis – always dapper – helping to pave the sidewalk in front of the home where the family had gathered to remember him. The cowboy hat was on the table, too. As well as an image of that 1962 truck.

The neighbor who called firefighters to the scene of the house fire that killed Vidal led the group in the recitation of the rosary, a Catholic tradition meant, in this case, to help a person pass from their earthly life into the peace and tranquility of heaven. The Hail Mary prayer is repeated 50 times, along with two other prayers repeated five times each.

“Santa María, Madre de Dios…”

Before the prayers, the family had spoken to us about Vidal’s death. They were horrified such a gentle and hardworking man died in such a violent and painful way.

And they fear that power outages continue to put their neighbors at risk.

“… ruega por nosotros pecadores.

Ahora y en la hora de nuestra muerte.”

Pray for us sinners.

Now and at the hour of our death.

Suddenly, during the recitations, darkness fell over the room.

The power had gone out, revealing three tiny candles on the table next to Vidal’s signature hat.

Flames filled the room with speckled light.

Cristian Arroyo, Valeria Collazo Cañizares, Karisa Cruz Rosado contributed to this report from Puerto Rico. CNN’s Sean O’Key, Sergio Hernandez, Natalie Gallón and Flora Charner contributed from Atlanta.