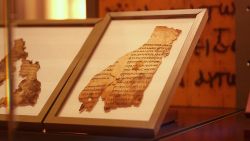

Small scraps of parchment inscribed with tiny Hebrew letters. They look like countries cut out of a map, or lost pieces from a jigsaw puzzle nobody could solve.

Some scholars say they’re fragments from the renowned Dead Sea Scrolls, Jewish texts that date to the days of Jesus. Others suspect they are expensive forgeries meant to dupe American evangelicals, including the family behind the splashy new Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC.

Last week, as the museum prepared for its grand opening on Friday, workers put finishing touches on its five floors of exhibits. They assembled the virtual reality ride through Washington, washed windows with clear views of the Capitol building, and wired the interactive displays that wind through the museum’s 430,000 square feet.

The museum’s exhibit on the Dead Sea Scrolls hasn’t been as easy to nail down.

With a price tag of $500 million, the Bible museum represents a heavy investment by its evangelical founders, particularly the Green family. Depending on your zip code, you may know the Oklahoma billionaires best for their chain of Hobby Lobby craft stores, or for their religious freedom battle with the Obama administration.

Either way, the Museum of the Bible’s goal is the same, says Steve Green, its founder and chairman.

“I hope that, as people leave here, they will get inspired to get to know the Bible’s story for themselves.”

The Dead Sea Scrolls are an important part of that story, Green says. Nearly 2,000 years old, they testify to the reliability of the Bible, to scripture’s timeless truths.

But Arstein Justnes, a professor of biblical studies at the University of Agder in Norway, says the Greens’ fragments tell quite a different story. This one is about a scandal in the world of biblical antiquities.

On his website, “The Lying Pen of Scribes,” scholars and scientists have identified more than 70 Dead Sea Scroll fragments that have surfaced on the antiquities market since 2002. Ninety percent of those are fake, Justnes says, including the Museum of the Bible’s.

If Justnes and other scholars are correct, the Dead Sea forgeries could be one of the most significant shams in biblical archeology since the “Gospel of Jesus’ Wife,” a fiasco that hoodwinked a Harvard scholar and made worldwide news in 2012.

Steve Green won’t say how much his family spent for their 13 fragments. But other evangelicals, including a Baptist seminary in Texas and an evangelical college in California, have paid millions to purchase similar pieces of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Some scholars believe they are all fake.

Kipp Davis, an expert on the Dead Sea Scrolls at Trinity Western University in Canada, is one of several academics trying to warn Christians, including the Green family, about the forgeries.

“The evangelical movement is really getting played here.”

‘They were buying everything’

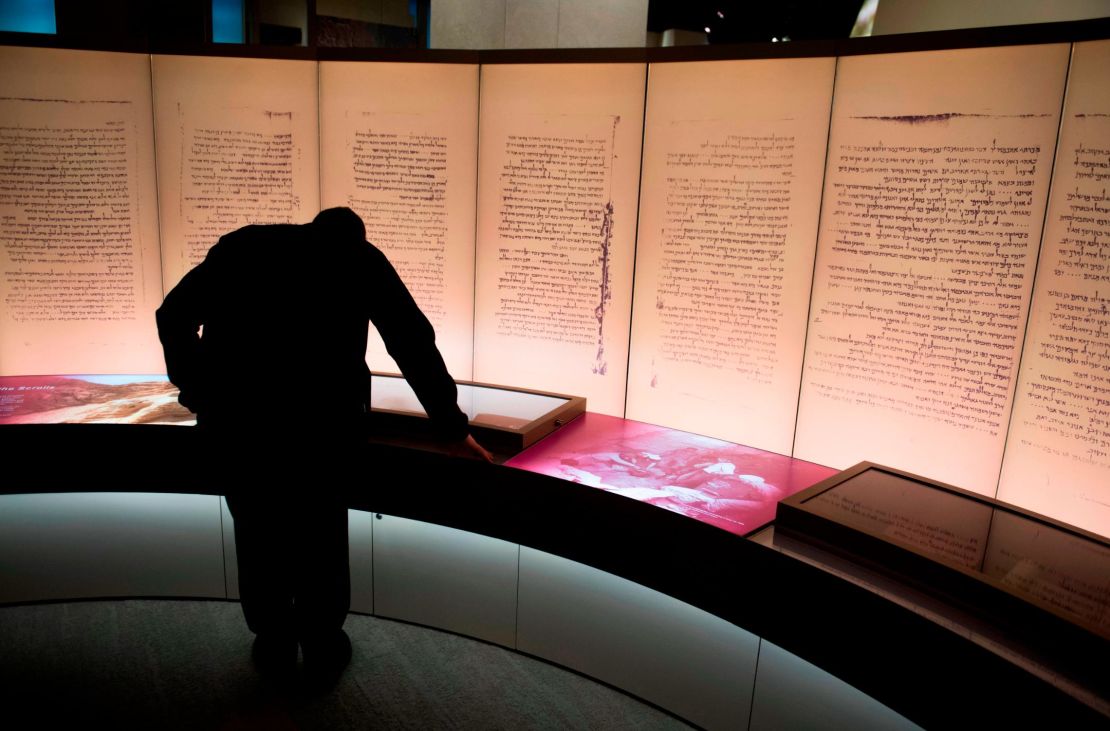

It’s hard to overstate how important the Dead Sea Scrolls are to biblical archeology.

“Any reputable Bible museum almost has to have Dead Sea Scrolls,” said David Trobisch, the Museum of the Bible’s director of collections.

Before the scrolls were discovered 70 years ago, the earliest and most complete version of the Hebrew Bible was from the 9th century.

But then Bedouin shepherds stumbled on the scrolls, hidden away for nearly 2,000 years in caves in Qumran, on the western shore of the Dead Sea.

The discovery was so vast, with more than 900 manuscripts and an estimated 50,000 fragments, it took six decades for scholars to excavate and publish them all.

The Israeli Antiquities Authority keeps a tight hold on most of the Dead Sea Scrolls, displaying them in the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. For decades, it was almost impossible for private collectors to get their hands on even scraps from the famous archeological find.

But in 2002, new fragments began mysteriously appearing on the market. The Greens bought their fragments between 2009-2014. At the time, they were deeply involved in the antiquities trade, amassing a collection of some 40,000 artifacts.

Some scholars accused the Greens of buying too many artifacts too quickly, without being sure exactly where they came from, or who had owned them in the past.

“They made it widely known that they were buying everything,” said Joel Baden, a professor at Yale Divinity school and co-author of “Bible Nation,” a new book about the Greens.

“Every antiquities seller knew the Greens were buying everything and not asking questions about anything.”

Eventually, the Greens landed in the crosshairs of the Justice Department, which said their company, Hobby Lobby, had received thousands of smuggled artifacts.

The company was warned that buying artifacts that were likely from Iraq carried risks that they had been looted, the Justice Department said.

But Hobby Lobby still bought 5,500 items for $1.6 million from a dealer in the United Arab Emirates.

On some customs forms, the smugglers listed the artifacts as “ceramic tiles” and estimated their worth at $1 per item, prosecutors said.

Hobby Lobby agreed to pay $3 million and return the artifacts as part of a settlement with the Justice Department.

“We should have exercised more oversight and carefully questioned how the acquisitions were handled,” said Steve Green, who, in addition to being chairman of the Museum of the Bible, is also president of Hobby Lobby.

Green also says the Museum of the Bible was not involved in the smuggling scandal.

But at a news conference at the museum last month, Trobisch said some of the confiscated objects had been destined for an exhibit on writing in ancient history. The museum had to borrow artifacts from another collection instead.

At the same news conference, the museum unveiled more stringent acquisition policies.

But some scholars – even those hired by the Greens – still have questions about the items already in the museum’s collection, including the Dead Sea Scroll fragments.

Dead Sea doubts

Almost immediately, Kipp Davis had doubts.

In the world of biblical studies, the 44-year-old still considers himself a “junior scholar.” He occasionally spices conversations with “Star Wars” references.

But in addition to his scriptural expertise, Davis also has experience in paleography, the study of ancient writing, which is often used to date manuscripts.

In 2014, the Greens hired Davis to prepare their Dead Sea Scroll collection for publication with a top academic book publisher. It was the kind of assignment that comes rarely in a young scholar’s career.

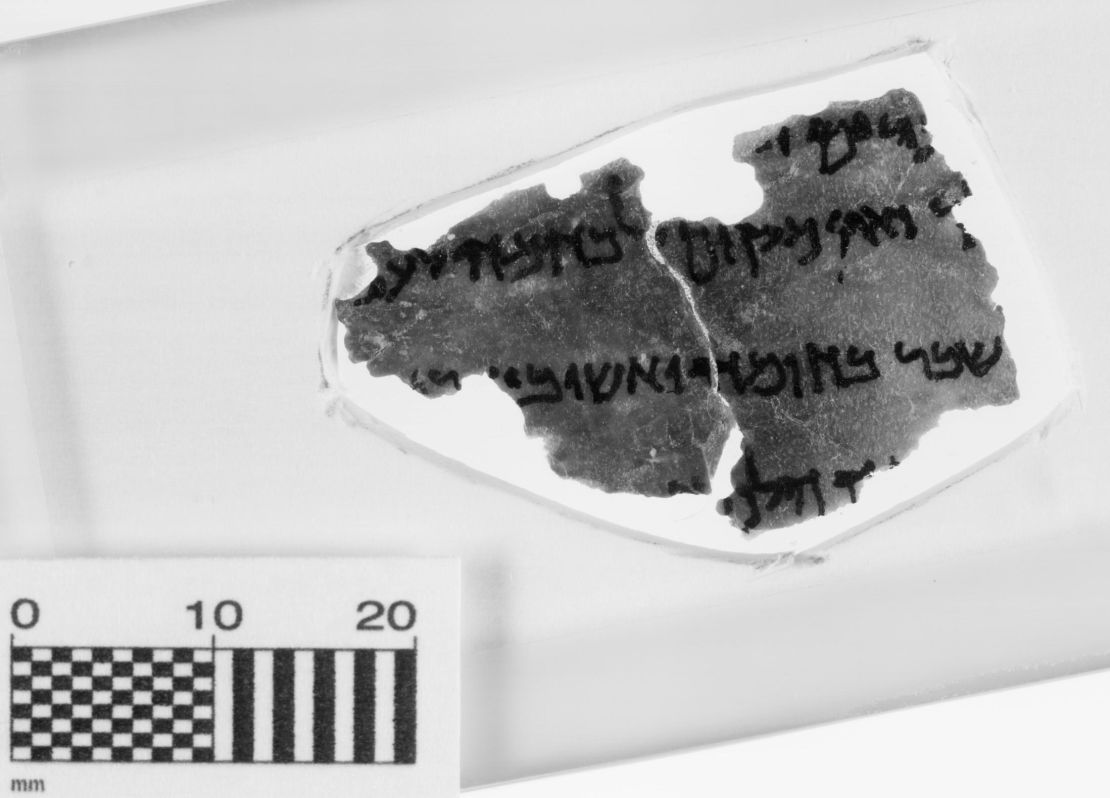

But as he looked at high-resolution and multi-spectral images of the Greens’ collection, something bugged Davis.

The leather parchment appeared ancient enough, but the writing looked stretched and squeezed to fit the misshapen fragments. Some had bleeding letters and other markers of a scribe struggling to write on a weathered surface. One fragment had what appeared to be an annotation from a 1937 edition of the Hebrew Bible, an almost unbelievable anachronism.

Paleography is an impressionistic science, which is a fancy way of saying that scholars often disagree about how to interpret its findings, and Davis is a careful scholar.

But the evidence added up, and he became convinced that at least six of the Greens’ 13 fragments are almost certainly forgeries.

They reminded Davis of other Dead Sea Scroll fragments he had studied a few years before. After he and other scholars raised doubts about the authenticity of nine, scientific tests confirmed that eight were forgeries. The tests were inconclusive about the ninth. In one instance, the forger had spread table salt on a fragment, perhaps hoping to simulate the sediment around the Dead Sea.

Justnes, the biblical scholar from Norway, believes all 13 of the Greens’ fragments are modern-day forgeries.

Rather than the smooth pen strokes of an experienced scribe, the writing on the fragments is “brutal and hesitant,” he says.

“They don’t look like authentic Dead Sea Scrolls.”

‘I have not seen the proof’

Emanuel Tov, a professor at Hebrew University in Jerusalem, is perhaps the world’s leading expert on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Davis calls him one of the most important biblical scholars of the last 50 years.

Like Davis, Tov was hired by the Greens to study their fragments and help edit the book about them. Tov says he is not convinced the fragments are fake.

“I will not say the Museum of the Bible has no inauthentic fragments,” he said. “I will say I have not seen the proof.”

The handwriting anomalies Davis describes also occur in authentic Dead Sea Scrolls, Tov says. To determine whether the Greens’ fragments are forgeries, they need to be compared to a larger sample size of scrolls.

“We should not be so fast in thinking that we know everything about the scribe of these little fragments. We need very thorough research on the intricacies of the problems with the handwriting.”

Like staffers at the Museum of the Bible, Tov also noted that one of the world’s leading paleographers, Ada Yardeni, has studied the museum’s fragments.

“She is accepted by everyone as the best paleographer in the world, and she has not raised one issue with the handwriting being non-authentic,” Tov said.

Yardeni did not respond to emails from CNN requesting comment for this story.

But Tov said he still has some questions about the Greens’ Dead Sea Scroll fragments.

For one, 12 of the 13 fragments bear snippets from the Hebrew Bible. That’s an unusually high percentage considering that less than a quarter of all known Dead Sea Scrolls pertain to scripture.

“It is a very doubtful situation that most of the new fragments that have come to the market after 2002 are biblical. It is really very fishy.”

But Tov said he had recently solved the riddle, perhaps. Maybe the fragments do not come from Qumran, where most of the Dead Sea Scrolls were found. Maybe they come from another spot in the Judean Desert, where biblical texts were more common.

Of course, that raises more questions about the Greens’ fragments. If they weren’t found in Qumran, where were they found? And who found them?

“I do not know such things,” Tov said. “Whether that’s good or bad, I don’t know. It’s probably not good.”

Where did they come from?

Clean cut and earnest, Steve Green projects an air of calm certainty, like a salesman who truly believes in the product he’s selling.

But on some matters related to his family’s expensive collection of artifacts, Green seems surprisingly uncertain. During a recent interview at the Bible museum, for instance, he said he wasn’t sure who sold him the Dead Sea Scroll fragments.

“There’s been different sources, but I don’t know specifically where those came from.”

The question of provenance – documentation of an artifact’s chain of custody – is crucial to museums and modern collectors, scholars say. It protects against forgeries and looting.

A growing number of scholars say artifacts without provenance should not be the subject of academic study or displayed in museums.

The Museum of the Bible has dealt with provenance problems before. Trobisch, the collections director, said the museum will not display a fragment of St. Paul’s letter to the Galatians because it cannot adequately trace its chain of ownership, including why it showed up on eBay in 2012.

But Trobisch says the museum knows – and will display – the provenance of the Dead Sea Scroll fragments.

All but one, he said, can be traced back to the Kando family, Palestinian antiquities dealers who became trusted middlemen between the Bedouins who found the Dead Sea Scrolls and the scholars who bought them decades ago. For years, the thinking among scholars has been: If an artifact came from Kando, it’s likely legit.

Still, Trobisch said the museum does not know where the fragments first came from.

According to Tov, the Kandos listed the fragments as coming from “Qumran Cave 4,” one of the 11 caves where Dead Sea Scrolls have been discovered. But both Tov and Trobisch question that.

“I personally don’t think anyone in the world can know where they came from,” Trobisch said.

William Kando, who runs the family business, could not immediately be reached for comment.

Some academics have their own suspicions about where they came from.

The world of Dead Sea Scroll scholars is small, and few have the level of skill and knowledge to forge believable artifacts.

“Whoever is behind this may be someone who we all know,” Davis said.

Meanwhile, several fragments from the Green collection were sent to a scientist in Germany for further study. It’s the same scientist who found forgeries in the other collection Davis studied. The results could be public as soon as next year.

At the Museum of the Bible, they’ve decided to “teach the controversy,” to borrow a phrase from the science vs. scripture fight over teaching evolution in public schools.

At a media tour this week, six fragments were displayed in the Dead Sea Scrolls exhibit, including three that Davis’ suspects are forgeries. When the museum opened, a display panel acknowledged some of the doubts about the fragments’ authenticity.

Here’s what the panel says:

Are these fragments? Research continues

In 2002, dozens of previously known “Dead Sea Scroll” fragments began appearing with antiquity dealers. Universities, museums and private collectors acquired many of these “new” fragments. As scholars began to study them, some noted puzzling features and labeled them as forgeries.

MOTB (Museum of the Bible) published the initial research on its scroll fragments in 2016, but scholarly opinions of their authenticity remain divided. Scientific analysis of the ink and handwriting on these pieces continues.