For the 1.8 billion Muslims around the world, the Hajj is considered a spiritual pinnacle. Each year, up to three million pilgrims descend on Mecca – the epicenter of the Muslim world – to seek redemption, to forgive and to be forgiven.

Wrapped in white cloth, worshippers embark on the five-day pilgrimage, considered one of the five pillars of Islam. All Muslims who are physically and financially able are required to make the journey to Mecca at least once in their lifetime.

Mecca is meant to be the bedrock of Muslim unity, with the Hajj lauded as a place where pilgrims shed class, race, and nation. In his 1964 pilgrimage, less than a year before his assassination, black civil rights activist Malcolm X marveled at the “spirit of unity” between white and non-white Muslims – he later disavowed many of his beliefs about racial separation on returning to the United States.

But as Saudi Arabia has taken a more muscular approach to foreign policy with the rise of a young Crown Prince, Mecca has emerged as a political fault-line. A diplomatic spat between Saudi Arabia and Canada over a human rights statement resulted in the closure of one of the main flights between Canada and the kingdom, reportedly complicating matters for hajjis, or Muslim pilgrims.

A bruising Saudi-led 2016 embargo on Qatar, and the dissolution of diplomatic ties with Iran in 2016 has also disrupted pilgrimages for nationals of those countries in recent years. In Yemen, the ongoing war between Houthi rebels and Saudi-backed forces has all but trapped millions of would-be Yemeni pilgrims.

Still, Mecca is brimming with over 1.5 million international pilgrims this year, according to Saudi officials. These are devout Muslims who tenaciously pursue the pilgrimage, enduring the inconveniences of an arduous journey and sidestepping hurdles put in place by a difficult political climate whose temperatures continue to climb, and ignoring a string of unbecoming stories about the Hajj, including stampedes, fires and sexual harassment.

They prefer instead to focus on spiritual nourishment that the Hajj promises to supply.

Entering Mecca

Many pilgrims converge on the city weeks before the start of the Hajj rituals.

Worshippers wear special white garments – men wrap themselves in seamless, stitchless cloth, while women wear a simple white dress and headscarf. The clothing is said to symbolize human equality and unity before God.

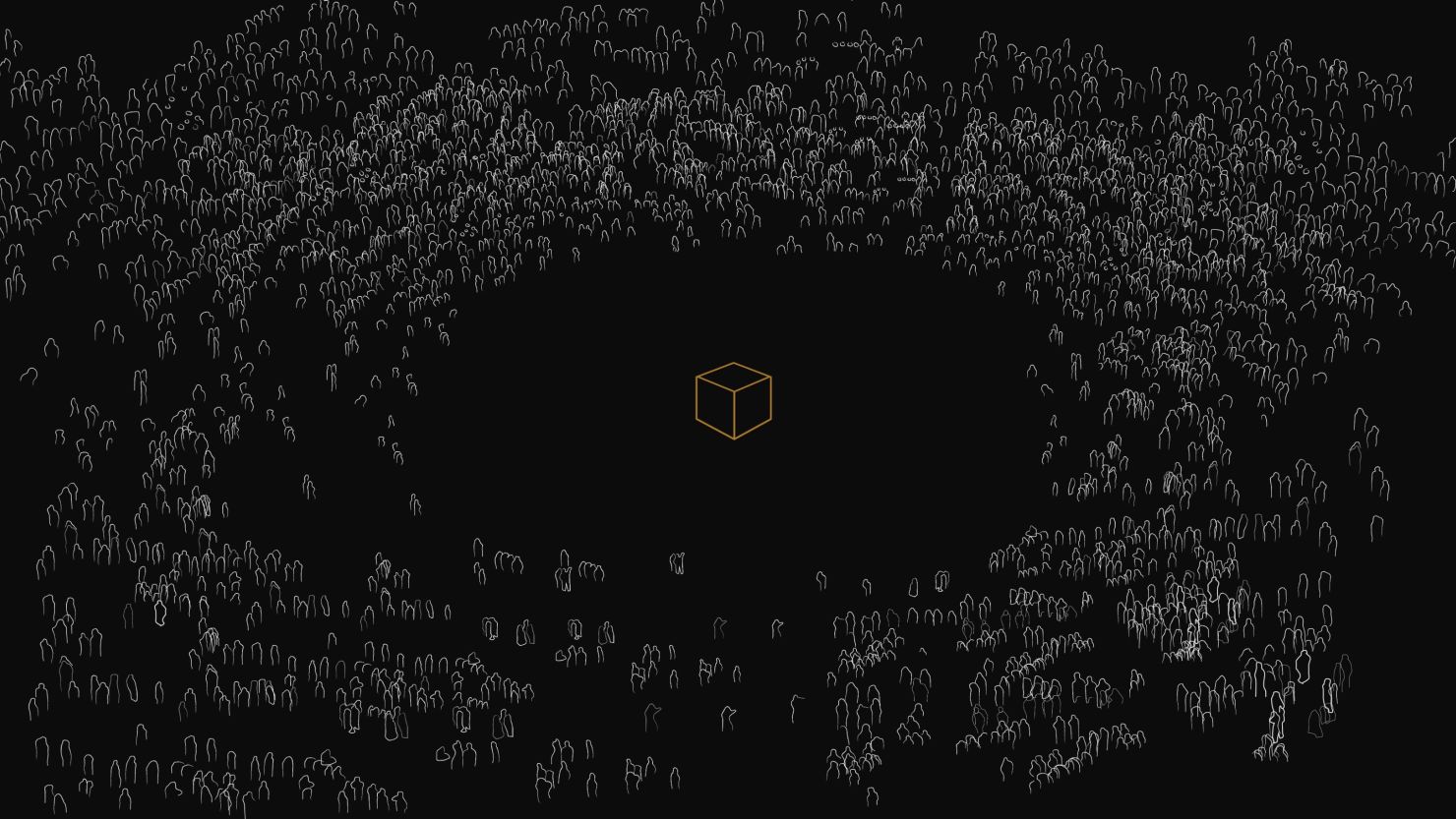

Pilgrims begin the Hajj with a circular, counter-clockwise procession around the Kaaba, a cube-shaped structure that Muslims believe the Prophet Abraham from the Old Testament constructed. It’s the most sacred shrine of Islam.

The Prophet Muhammed made the first Islamic pilgrimage in the year 628 AD, when he set out to Mecca with 1,400 of his followers. Mecca is considered to be a city for all Muslims and only Muslims. Non-Muslims are denied entry at all times.

Because of the centrality of the holy sites to the Muslim world, the Saudi monarch’s preferred title is “Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques,” referring to the Grand Mosque in Mecca and the Prophet’s Mosque in nearby Medina.

Saudi authorities manage the entry and exit of pilgrims through strict visa applications and have a dedicated Hajj ministry, employing 40,000 workers. In the last 10 years, 24 million Hajj pilgrims have visited the city. Thousands of civil servants are deployed to the pilgrimage each year.

A global tent city

To go through the six steps of the Hajj, pilgrims walk in massive processions, shoulder-to-shoulder with Muslims from more than 80 different countries. Together they share meals, prayers and very close living quarters.

“Groups of West Africans in colorful garb, almost singing verses from the Quran. Old Chinese couples, groups of blonde Europeans and Americans; it felt as if we were watching the entire world walk past,” wrote CNN’s Schams Elwazer who covered the pilgrimage for CNN in 2005, 2006 and 2007.

Sermon on the summit

For the third major Hajj ritual, Muslims gather at Mount Arafat, where the Prophet Muhammed is believed to have delivered his last sermon.

Upwards of a million pilgrims sit on the mountain, blanketing the site in white, while umbrellas used to shield the worshippers from the sun provide flashes of color.

This is the climax of the pilgrimage. Muslims perform day-long prayers, incantations and recitations from the Quran. It is not uncommon to see worshippers shed tears as they reach this peak of spiritual cleansing. Saudi Arabia’s top clerics traditionally lead a Hajj sermon on this site.

Gender and Hajj

Mecca is the only Islamic holy site where men and women all pray together and perform all the Hajj rites together. In most mosques, women and men are assigned separate areas for worship, and when one room is available, women are expected to pray behind the men.

Authorities only segregate men and women at the Hajj in terms of sleeping arrangements.

According to the Brookings Institute’s study on Hajj pilgrims, hajjis report more positive views of women’s abilities and a greater concern for their quality of life after performing the pilgrimage. They are also more likely to favor educating girls and encourage female labor participation.

Still, reports of sexual harassment have plagued the ritual of late. Earlier this year, five women told CNN about their experiences with sexual abuse at the pilgrimage. One British woman, who preferred to remain anonymous, said she had never been sexually assaulted before going to the Hajj, where her breast was forcefully, and painfully grabbed as she headed into the Grand Mosque.

“Talking about sexual assault is difficult enough and talking about it in connection with the Hajj, which is a pillar of Islam, is even harder because it is sacred,” she said.

One unnamed Saudi official said the allegations were being taken seriously by authorities, although it is not immediately clear if the kingdom has taken extra steps against harassment at the pilgrimage this year.

Dress codes for women are strict and even a wisp of hair escaping from the required headscarf can prompt frowns, or worse, from the crowds.

Stoning the devil

During the “stoning of the devil,” pilgrims lob rocks at three pillars, known as the “Jamarat,” symbolizing the rejection of the devil’s temptation.

The ritual marks the beginning of the four-day Eid al-Adha holiday, known to Muslims as the “big Eid.”

Muslims celebrate the Adha – the Arabic word for “sacrifice” – by slaughtering sheep and distributing the meat to the poor.

This is also the most dangerous part of the pilgrimage. People stream back and forth between the pillars and the Kaaba, posing a major crowd control challenge for organizers. Many have been wounded or killed by stones thrown from further back within the crowd.

Two years ago, more than 700 people were killed and nearly 900 were injured in a stampede while performing this ritual.

Since then, Saudi authorities have spent millions of dollars renovating the area, making it multi-layered instead of a flat plain, and renovating the pillars.

Becoming a Hajji

After five days, the Hajj comes full circle and worshipers return to the Grand Mosque for their final prayers.

For pilgrims and Saudi civil servants alike, the end of Hajj is the time to return to family and celebrate the remainder of Eid al-Adha.

At home, the pilgrims are greeted with fanfare. Congratulations from neighbors pour in and their homes are usually decked out in festive lighting.

The Hajji now has a somewhat elevated social status. A person who has completed the pilgrimage can add the phrase al-Hajj or hajji (pilgrim) to their name.

This story was first published in August 2017 and has been updated. CNN’s Gianluca Mezzofiore, Kevin Taverner, Byron Manley and Schams Elwazer contributed to it.