Editor’s Note: John D. Sutter is a columnist for CNN who focuses on climate change and social justice. Follow him on Snapchat, Twitter and Facebook

Rain pounded on the roof of the mobile home as the phone rang. The call was about Mark, Carolyn Ruffin’s oldest son. He’d been hospitalized in a nearby town. The mother of four, who normally has an unflappable air about her, knew she had to rush to her boy – no matter that a storm was brewing, the likes of which her corner of Louisiana never had seen.

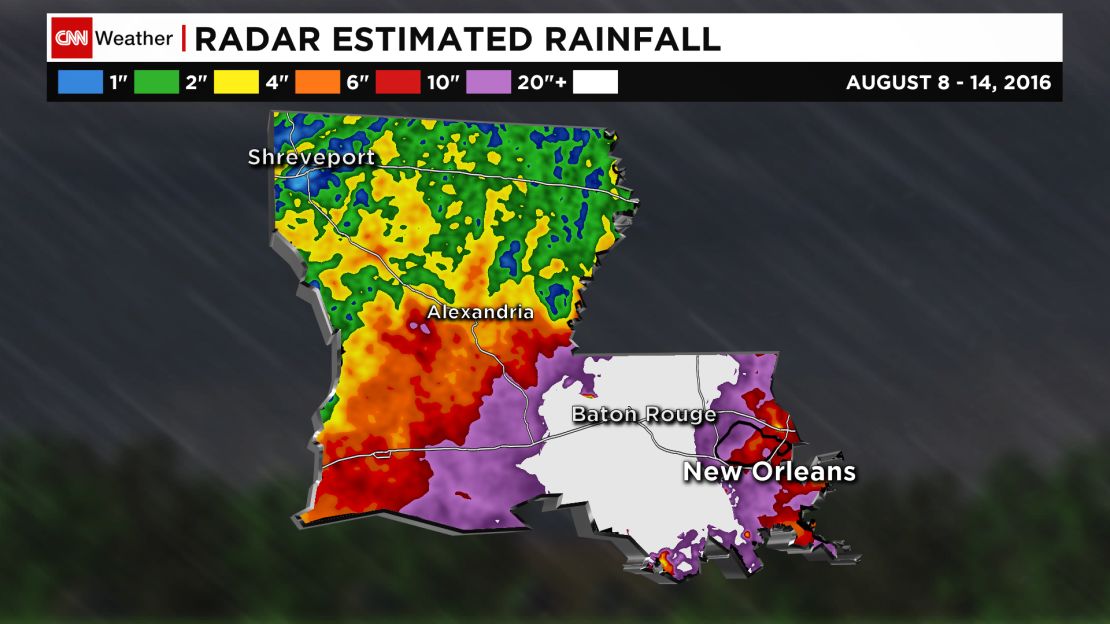

This was August 12, 2016. In the next week, about 7 trillion gallons of water would fall on Louisiana, more than during Hurricane Katrina, according to meteorologist Ryan Maue. The nameless storm would shatter records, flood homes and kill 13 people.

That morning, though, Carolyn’s thoughts weren’t focused on the weather. They were with her son. So, at about 7 a.m., she hopped in the front seat of a friend’s pickup truck.

Two people would join her. One was Alfred Waxter, the truck’s owner, a close family friend visiting from Mississippi. The other was Carolyn’s daughter Stacy.

At 44, Stacy Ruffin was the youngest of Carolyn’s four children. Family members speak of the two as inseparable, and they mean it literally. Stacy lived with her mother in the mobile home, raising a daughter and son of her own there. She managed the deli counter at the Walmart in a neighboring town. Otherwise, she was at her mother’s side, helping run errands, pay bills, check on neighbors. Stacy’s eight aunties and uncles – and their children – all were part of her flock.

She was the family caretaker. The responsible one. The one you turned to.

So it’s no surprise she went with her mother to check on her brother.

And it’s no surprise that, one year after the storm, no one has filled her void.

‘Natural’ disaster

Hundreds of miles away, the email landed in the scientists’ inboxes.

It was four days later, August 16. The request: Would Karin van der Wiel, Sarah Kapnick and Gabriel Vecchi – three researchers from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s lab in Princeton, New Jersey – help assess the extreme rainfall in Louisiana?

The floods in Louisiana had caught the attention of the World Weather Attribution team coordinated by Climate Central, a nonprofit that focuses on climate change science and journalism. And they wanted help.

The team would be assessing the Louisiana storm for any signs of climate change. Was this storm more likely because humans are polluting the atmosphere with heat-trapping gases? Did climate change have any likely influence on the extreme rainfall totals? Or was this a truly “natural” disaster?

Karin and Sarah considered the proposal.

The result of their inquiry would be published no matter what they found, but they had to work fast. Scientific studies typically play out over months, if not years. Could this massively complicated work be done – and quickly enough to capture the public’s attention?

The researchers knew they’d have to drop everything else to focus on this project. But they had the expertise, and they had the climate models at NOAA’s Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory.

Plus, there was something about this flood.

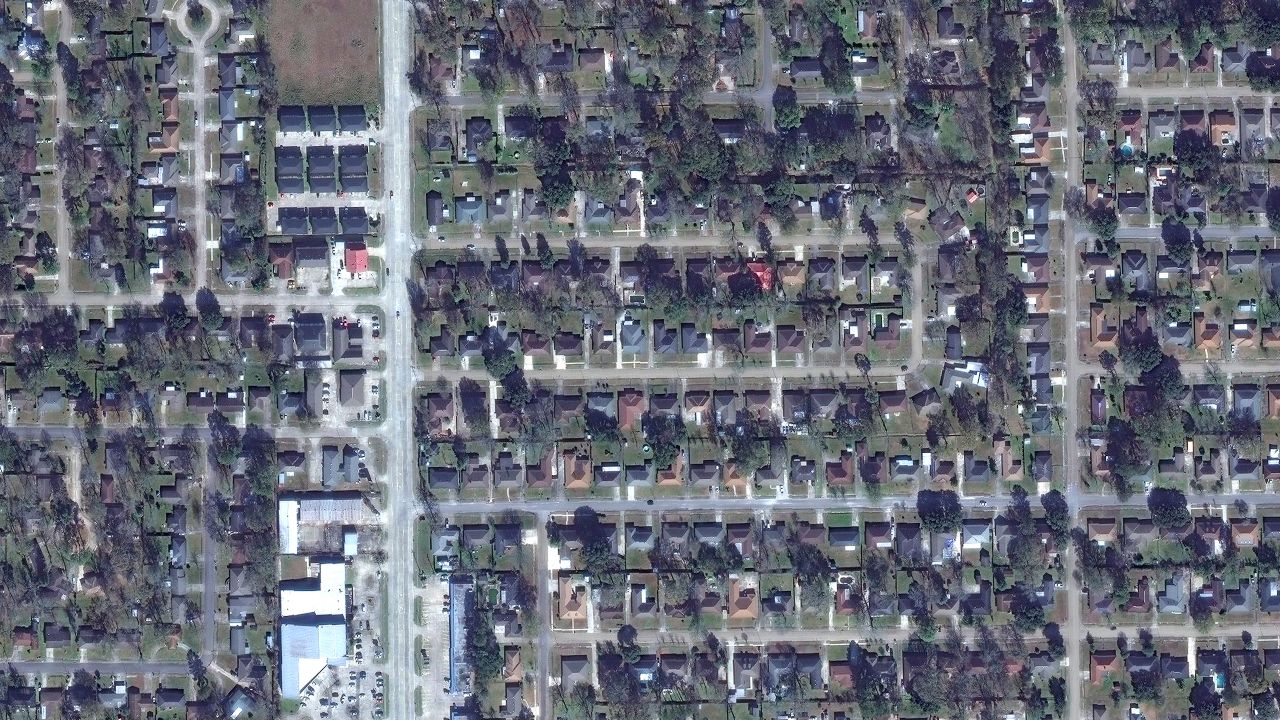

It seemed to have the drenching power of a tropical storm, yet it stalled on land, dumping trillions of gallons of water on southeastern Louisiana, day after day. All three scientists had seen the news coverage: the floating cars, the submerged homes, the people trapped on their roofs. Many rescues were taking place by boat, since cars couldn’t travel the streets in the disaster zone. A “Cajun Navy,” made up of volunteers, aimed to make up some of the gaps left by authorities. Some 60,000 homes were damaged. Financial losses were estimated at $30 million.

The scientists took the news to heart. They felt for the people on the ground. Sarah and Gabriel have children of their own. What if their own family members had been put at risk?

They agreed to discuss the matter further on Skype with the Climate Central team. The three of them crowded behind a laptop webcam at the lab.

What would it take to pull this off?

‘On her way home’

Stacy and Carolyn Ruffin reached St. Helena Parish Hospital safely.

Not that the drive was easy.

First, they tried to go west on Highway 10 but had to turn back. An 18-wheeler was stuck in the ankle-deep floodwater. So they tried another route: Highway 1045, a winding backcountry road that’s elevated above the bogs and gullies overgrown with oak, pine and ivy.

It’s not a road the Ruffins normally take, but that morning, it seemed to be the only safe route.

The family arrived to tragic news, however.

Mark already was gone.

Doctors believed that Mark Wilson suffered a heart attack on the job at an industrial site, said Brad Graves, chief of St. Helena Parish Fire District No. 4, which handles emergency services.

Carolyn wailed at the loss of her son.

Stacy phoned her children. Courtney, 23, and Corey, 13, needed to hear the news of their uncle’s death from their mom. They needed her voice to console them.

“She said she loved us and she was on her way home,” Courtney recalled.

The words didn’t land quite right. There was something about her mother’s tone.

Soon, Stacy and her mom were back in the truck, with Alfred behind the wheel. Stacy sat in the passenger’s seat, her mother in the middle. Again, they headed down Highway 1045.

It wasn’t safe anymore.

The flood came in a flash – water rushing in from everywhere and nowhere all at once.

“It was like if you had opened a floodgate,” Carolyn told me.

The driver tried to turn back, threw the truck in reverse.

A jolt. The truck shook. The water took hold, pulling the vehicle into the abyss.

Carolyn and Alfred managed to get out of the driver’s side window.

Carolyn surfaced. Floodwaters rushed and swirled around her so swiftly, it felt like it was gushing from a fire hydrant. Carolyn gasped for air and flailed against the current.

She scanned the surface for her youngest daughter.

Stacy was nowhere to be seen.

Climate detectives

Was that climate change?

Karin, Sarah and Gabriel, the researchers at NOAA, were used to being asked that question. Until recently, however, they were able to answer in only the most sweeping of generalities.

There’s a great deal of scientific certainty that humans are polluting the atmosphere with heat-trapping gases, causing the Earth to warm. Already, researchers have observed about 1 degree Celsius of warming to average surface temperatures since the Industrial Revolution, when people started burning coal. Burning that fossil fuel, along with natural gas and oil, contributes to a build-up of carbon dioxide and methane in the atmosphere. Those gases traps heat, warming the planet.

These conclusions may be controversial with the Trump administration in the United States and with the 47% of Americans who say that global warming is natural or that they’re unsure what’s causing it, but they’re not – at all – with scientists. They’ve been researching this for decades.

The consequences of global warming also are well-known and observable now: Ice is melting in the Arctic, sea levels are rising, and coral reefs are struggling to survive. Broadly, rainfall events are expected to become more intense in some parts of the world as a warmer atmosphere helps clouds hold more moisture; worsening droughts are expected elsewhere.

That’s the global picture, though.

Attributing one storm, in one place, on one day, to climate change?

That’s difficult. And that’s new.

Peter Stott, who now leads the climate monitoring and attribution team at the Met Office, the United Kingdom’s national weather service, was the first scientist to try it.

The idea came to him on vacation in Tuscany in 2003, he told me. It was the middle of a massively deadly heat wave in Europe.

Temperatures hit 40 degrees Celsius – 104 Fahrenheit – “which I’d never experienced before,” he said. One night, sitting on a balcony overlooking a valley in Italy, it hit him: This heat wave covered such a wide area of Europe, and lasted for so long, that there would be a wealth of data about it. Could there finally be enough information, he wondered, to see how climate change had affected this heat wave?

That hunch resulted in a 2004 paper in the journal Nature, which is widely regarded as the first “climate attribution” study in the world. You can think of Stott almost like a climate change detective, looking for humanity’s fingerprints on a disaster that, to many, seemed natural.

But was it?

Stott and his collaborators used climate models – computer programs that approximate weather and temperatures over time – to compare observations from the 2003 heat wave with a computer-assisted approximation of the climate without human greenhouse gas pollution. In essence, this data helped them compare the likelihood of that heat wave in 2003 versus the likelihood of the same heat wave occurring in a climate before all of the pollution.

“The chances of it had more than doubled,” Stott told me.

The 2003 heat wave was more than twice as likely because of global warming.

There was intense public interest in that finding, especially in Europe.

And especially given another grim fact: 22,000 to 35,000 people died in the heat.

‘Praying up a storm’

The water rose around their necks. The truck was underwater.

Carolyn and the driver clutched a shrub together, fighting the current and hoping to be rescued. Carolyn had screamed so much that her voice was hoarse, but she doubted it could be heard above the water’s roar.

And neither of them had seen Stacy.

Hours passed.

“I’m going to help you get up on this little limb,” Alfred told Carolyn, pushing her onto the branch of a pecan tree. The water, which had been up to her throat, now hit her armpits.

“Hold on here some kind of way,” he told her. He was going to go for help.

“Can you swim?” Carolyn asked.

“A very little bit.”

Neither Carolyn nor Stacy could swim at all.

Carolyn watched her friend float into the distance.

“Maybe someone will find me,” she thought.

And maybe they’ll find Stacy.

Soon, night began to fall over Louisiana. Crickets and frogs added their screeching chorus to the roar of the flood. Sticks slammed into Carolyn’s back. Logs hurtled past. Mosquitoes nipped at her shoulders and face, covering her skin with pockmarks. Her mind began to race.

“Stacy! Stacy!” she screamed.

She thought of her son Mark, who’d died that morning. It felt like an eternity ago. Mark loved football, graduated from high school and played ball for a year at junior college. He’d grown into a devoted husband and father of three. A guy who could fix anything. What would become of Mark’s wife? His children? That loss was so fresh, it stung.

And she thought of Stacy. Was her daughter alive? She had to believe so. Downriver, perhaps, hanging onto another tree. Or maybe she had been swept ashore. Maybe she was safe.

The more time she spent in the water, though, the more Carolyn let herself consider the unthinkable. She couldn’t stomach it. “Stacy!” She had to keep up hope. Yet her mind drifted back to the crash, to the moment the truck flipped off the road and listed into the water. Where did all that water come from? she wondered. It didn’t make sense – all this water, so fast.

She’d lived in the same location since the 1960s. It was like nothing she’d ever seen.

She played the accident over and over in her mind.

She heard her daughter’s last words.

“We gonna die,” Stacy had said just before the crash.

“We gonna die.”

Their families had reported them missing. But no one knew their precise locations. Six feet of water covered the pavement of Highway 1045, the local fire chief said, perhaps 12 feet of water where Carolyn was stranded, making the area nearly inaccessible.

Carolyn didn’t know whether anyone was looking for her.

As the sun set, she began to have visions. She saw a family outside a mobile home, just across the way, through some trees. “Help!” They couldn’t hear her over the roar of the flood.

“Help!”

One person appeared to be tacking a blue tarp onto the roof, trying to prevent the thumping rain from entering the home. Carolyn hollered and hollered, hoping to get their attention.

The family looked so real, she told me.

Now, she thinks they were a hallucination.

“They ain’t gonna find me,” she thought. “I’ll end up dying out here.”

She shivered in the cool water, still clutching the branch of the pecan tree.

“I sat there all night long – all night,” Carolyn told me. “Praying up a storm.”

‘Keep track of it’

It would be the first such rapid assessment of a storm in the United States.

Karin and Sarah – known in their Princeton lab for being problem-solvers who never give up – would apply their relentless drive to answer big questions about how the Earth works.

Karin, in particular, long had been fascinated by weather and water.

She grew up in The Netherlands, a country known for mastering the sea. Before climate change started raising ocean levels around the world, the Dutch were building intricate systems of dikes and canals so people could live in and around the water. That was necessary because much of the Northern European country was – and is – well below sea level.

As a teenager, Karin started making observations of her own, taking detailed notes about weather patterns in the family garden. She noted, for example, the daily minimum and maximum temperatures at that one location for three consecutive years. “I would write it down and make graphs,” she told me, laughing at how “nerdy” that sounds in retrospect. “You could see winter is colder than summer. You didn’t really learn spectacular things about this.

“But I learned you could keep track of it.”

Keeping track would become her calling.

At NOAA, she worked on climate models, evaluating these massive computer datasets to see how closely they tracked with observed weather patterns in the real world. In particular, she focused on rain patterns in the United States and how they’d shifted over time. Were the models good enough to approximate the way rain fell in the real world? Two models – FLOR, for Forecast-Oriented Low Ocean Resolution model, and HiFLOR, the higher-resolution version – were good at tracking with reality, Karin and Sarah wrote in a 2016 study published in the American Meteorological Society’s Journal of Climate. This was a big deal in the scientific community, since so many factors contribute to where it rains and when and how.

These models were “state of the art,” Sarah told me.

And they might enable researchers to do the kind of analysis Peter Stott had on the 2003 European heat wave. Extreme rainstorms are more complex, scientifically, than heat.

Their work was creating new possibilities.

But Karin and Sarah’s article on climate and rainfall published to little public fanfare.

Until the flood.

Soon, the New York Times was quoting their work, and they were embarking on the biggest scientific quest of their young careers.

‘I’m right here!’

The moonlight kept Carolyn alive through the night.

She’d been in the water nearly 16 hours. She’d survived this long, she started to believe that God was protecting her. Maybe God wanted her to find Stacy. Maybe she needed to take care of her daughter’s children, if Stacy had drowned. Either way, God showed her a sign that night, she told me. A beam of moonlight shined right down on her, giving her comfort. That light – and her belief that perhaps someone was looking out for her – helped her fight off sleep and survive.

Still, she was stuck on the limb of a pecan tree, unable to swim.

As the sun rose, she decided to make a push for shore.

She shoved off of the branch and into the water, expecting that she’d be able to stand.

She couldn’t. And her foot was stuck in a fork in the branch. The rush of water yanked her down and under, stealing her breath. She pulled and pulled, but her foot wouldn’t come loose. The water pulled her under once. Twice. The third time she went under, worrying that she might never surface again, she told me, she yanked again. Her ankle slipped out.

She was free. But she couldn’t swim to safety.

So she managed to grab another shrub and hold tight.

It turned out to be enough. That morning, she told me, a man – a real man, not a vision – drove down Highway 1045. Carolyn screamed and screamed. At first, it seemed he couldn’t hear her. The man continued down the road and out of Carolyn’s vision. But he stopped and turned around, drove the other way. She screamed again, and this time he pulled over.

She was so far down in the water, he couldn’t see where the voice was coming from.

“I’m right here!” she yelled, water up to her neck.

The man told her to hang on, disappeared from view and returned not five or 10 minutes later, with rescuers and a boat. Carolyn was rescued at 8:41 a.m., according to local fire department records.

Her survival was “the grace of God,” said Graves, the fire chief.

Rescuers wrapped Carolyn in blankets and took her to safety.

Later that day, she learned of her friend’s fate – and Stacy’s.

Alfred, the truck’s driver, was found more than two miles away – alive.

Stacy’s body was found near the crash site.

She escaped the car but died in the flood.

Her certificate of death lists her fate as an “accidental” drowning.

‘One-in-70-year storm’

On September 6, after days of intense research on the nature of the deadly floods in Louisiana, Karin gave seven interviews. She’d never even talked to a journalist before.

A press release about her study on the Louisiana rainfall and climate change was due to be published online the next day, a collaboration with eight other researchers around the world from New Jersey to Nairobi. The bulk of the work had been done in just two weeks, with Karin and Sarah taking the lead on the writing. They met daily in front of the webcam with the global team, hammering out the analysis. A supercomputer at a US government lab in Tennessee had run the massive calculations as part Karin’s previous research. And those data now proved invaluable.

Days were long, often keeping the researchers working until midnight or later.

But they had the results, and they knew they needed to communicate them widely.

The first interview of the day was with Amy Wold, a newspaper reporter in Baton Rouge, the epicenter of the storm. “What would have been a one-in-100(-year) storm (in 1900) would be a one-in-70-year storm (now),” Karin told the Advocate reporter. “That’s quite an increase.”

Put another way: The storm was at least 40% more likely, and perhaps much more, because of climate change, the study found. And it could be expected to be 12% to 35% more intense because of human greenhouse gas pollution.

Louisiana flooding is 'major disaster,' governor says

The climate detectives found human fingerprints on the August 2016 floods.

Karin and the other researchers arrived at these results by running two sets of experiments with the climate models. They tested how likely this storm – with its extreme rainfall – would have been in 1900, before most man-made global warming. And they compared those results with how likely this particular storm was to occur in 2016. This built on Karin’s previous work.

The results don’t say definitively that climate change caused the extreme rainfall. But they do say that the storms were made more likely – and possibly more severe – because of global warming.

These findings mirror what climate scientists understand about global warming and rainfall, generally. Because of pollution, extreme storms are becoming more of the norm.

These results raise yet another question that goes beyond the science.

If climate change made the storm more likely, who – or what – killed Stacy Ruffin?

‘The records were shattered’

I visited Stacy Ruffin’s family earlier this summer. Her mother offered me a seat in the shade of their front lawn and, not long after I arrived, handed me a stack of papers tied with a blue ribbon.

“A loving farewell. Mark Wilson. Stacy Ruffin.”

“You have some really nice photos of her in here,” I told Carolyn, awkwardly, not sure what to say about the funeral program for her two children who died the same day.

On the cover, Stacy’s hair is piled high on her head, a stylish ringlet dipping down beside her eye. Inside, she’s wearing hoop earrings and a striped turtleneck. Only later would I learn that the family’s house burned down years ago, and they lost nearly all of their family photos.

These were their only surviving memories.

So much about the storm doesn’t make sense. Some people say you have to accept the mystery. The storm “was an act of God,” and sad as it may be, it must have been Stacy’s time to go. That’s what Stacy’s coworker Rose Franklin told me at the Walmart deli counter.

Others are searching for answers.

Deloris Wilson blames herself for her niece’s death. She had suggested that morning that Carolyn and Stacy take Alfred’s truck to the hospital, thinking its height would rise above the water. If they hadn’t, she says, maybe they never would have tried to drive on Highway 1045. She knows it might have made no difference, but the guilt has weight.

Courtney, Stacy’s oldest child, blames herself, too. She’d wanted to go with her mother that morning, but there wasn’t room in the truck, and they’d wanted to keep tools in the back. What if Courtney had insisted? She’d taken swimming lessons. Could she have saved her mother’s life?

Likewise, Carolyn does not accept the death as natural.

As she clung to the pecan tree, floodwaters rushing past, she fixated for a time on one thought, she told me: “Where did all this water come from?”

So much water. It had to have come from somewhere.

Carolyn told me she believed that a dam had malfunctioned north of the crash site, in Mississippi. Perhaps it had cracked and then given way?

It no doubt seemed that way, said Ken Graham, meteorologist-in-charge at the National Weather Service office that covers the New Orleans and Baton Rouge region. But there were no infrastructure failures of that type, he said. What Carolyn witnessed was a “historic” flood.

Graham pointed to river gauges near Denham Springs, Louisiana. The previous record height for the Amite River was 41.5 feet, in 1983, he said. Last August, the river crested at 46.2 feet.

“This wasn’t just a little above the record,” he said. “The records were shattered.”

Near the end of my visit, I presented some of this information to Carolyn and Courtney.

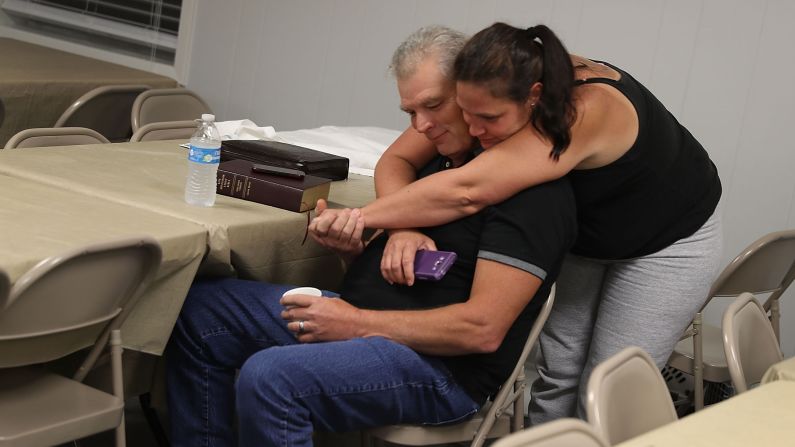

We were sitting at the kitchen table, the only remaining photos of Stacy scattered about. One of her at a pizza parlor, years ago, a warm smile on her face. That smile was Stacy’s essential quality, her mother told me. Even as a baby, Stacy always seemed to be grinning about something.

I pulled up an article about Karin’s climate attribution study on my phone. And I told them the gist, which is that global warming made this storm more likely and may have strengthened it.

They paused, taking it in.

I wondered what conclusions Carolyn drew from that information. But I was afraid to ask.

Does this information change the way she feels about her daughter’s death?

Who – or what – killed Stacy Ruffin?

Scientists, of course, don’t feel comfortable answering that question. They want to stick to observations, to the measurable facts of the atmosphere and other Earth systems. That’s fine. But some attorneys and ethicists are beginning to explore the murky moral questions posed by the science of climate attribution, by an era when many disasters no longer are “natural.”

If science can tell us that a certain storm was more likely, or more severe, because of climate change, couldn’t someone – somewhere – be held liable for the pollution that contributed to the deaths and property damage associated with that storm?

I called five climate law experts to ask that question.

All said no. At least, not yet.

The reason for the disconnect, said Dale Jamieson, a professor of environmental studies and philosophy and an affiliated professor of law at New York University, is that our moral compasses aren’t built to take climate change seriously.

Consider the typical Jack-and-Jill crime, he told me. Jack steals Jill’s bike on purpose. It’s clear, in this scenario, that Jack is to blame, and Jill is the victim. Jack meant to harm Jill.

Now, consider a climate-change scenario. Jack drives to work in a high-polluting Hummer, which does contribute somewhat to global greenhouse-gas emissions. Maybe he buys electricity from a utility that gets its energy from a coal-fired power plant. That contributes, too.

Now, Jill dies in a flood that scientists say was made much more likely by global warming.

Is Jill a climate-change victim?

It would be difficult to say so definitively. What local conditions contributed to the flood that killed her? Were local governments promoting development in flood-prone areas? Were the streets graded safely? Did she choose to drive out into the flood; if so, does she share some blame?

In the case of Stacy Ruffin, you could criticize the family’s decision to drive into a flood. You also could criticize local and state governments for rubber-stamping development in flood-prone areas and for planning but not building infrastructure designed to lessen the rush of floodwaters, said Craig Colten, professor of geography at Louisiana State University.

Colten pointed to a canal diversion project that was proposed after a 1983 flood; it would have helped drain water from a part of Louisiana devastated last year, Colten said. “They’ve only dug one part of it,” he said. “It’s far from being complete.”

Next, is Jack a climate-change perp?

Yes, but so are all other fossil fuel users around the globe. Perhaps you could blame Jack for only the percentage of global-warming emissions he contributed? That was the approach a Peruvian farmer, Saul Lliuya, took when he sued a German electric company over its alleged contribution to the melting of glaciers near his farm. The farmer tried to hold the power company, RWE, liable for some of the damage and asked the court to determine the company’s percent contribution to global emissions, according to a report from the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia University. A judge threw out the case, saying there was no “linear causal chain” between the German company and the Peruvian glacier, the Columbia report says.

Maybe that doesn’t feel quite right? Try blaming the government.

A group of 21 young people are suing the Trump administration in federal court in Eugene, Oregon, for allegedly violating their constitutional rights to life, liberty and property by supporting the development of fossil fuels when science shows those fuels are harmful. Some major questions plague that case, however, including: Why is the United States liable and not China, which now is the biggest climate polluter annually? And does the US government really control all aspects of energy policy, or do consumers and fossil fuel companies share in this, too?

The resulting quagmire is a situation in which harm is clearly being caused – the World Health Organization expects climate change to cause an extra 250,000 deaths per year between 2030 and 2050, with those coming from increased cases of malaria, malnutrition, diarrhea and heat stress – but everyone seems to be to blame.

And therefore no one is to blame, as well.

“Part of the problem, I think, with the whole climate change issue … is, it is really different from other kinds of issues that humanity has faced,” said Jamieson, from NYU. “And that creates two problems: Because it’s different, we really don’t know what the hell we’re doing in trying to think about it. And the other is, we always try to domesticate it and make it conform to some other model we do understand.”

In this case, he said, we should throw out the Jack-and-Jill crime model entirely.

Climate change is different. It requires different thinking.

I asked Jamieson: Did we all kill Stacy Ruffin?

Yes and no, he said.

The real point is to figure out how to avoid causing climate-related deaths. Perhaps the most effective and simplest way to start, he said (and many economists would agree), is to create a carbon tax.

“What that says is, ‘OK, you’re going to emit (greenhouse gas pollution), and that’s going to increase the probability of screwing up the world,’ ” he said. “But you’re going to pay for that. And we’re going to take that money, and we’re going to use that money to try to compensate the (people harmed or killed by climate change) and to help people adapt.”

The other thing that’s critical, Jamieson said, is understanding that just because you – or your country – didn’t cause all of global warming, that doesn’t mean you’re not part of it.

And just because it may be impossible to prove, in court, that climate change killed a particular person or flooded a particular house, that doesn’t mean real losses aren’t occurring.

“You have to put a face on the victims.”

‘I can never see her face’

The year after the storm has not been easy for Stacy’s family.

Her daughter, Courtney, left a nursing program at Southeastern Louisiana University and quit a job at a local hospital after the storm, she told me, because both reminded her too much of death.

She hopes to continue studying nursing but needed to step away.

Stacy’s mother has become consumed by the mystery of the water.

I finally got up the courage to ask Carolyn about global warming and the flood – about the role of climate change in making freakish storms more likely.

Carolyn told me it made sense that global warming probably supercharged the storm. And she told me that everyone who burns fossil fuels – beyond what they absolutely need – contributes.

“Really, I would like to know myself” if global warming contributed to Stacy’s death, said Carolyn. “I’m 69 years old, and I’ve never been in nothing like this.

“I’ve never seen water like that.”

Are people who contribute to global warming to blame for Stacy’s death?

Yes, she told me, if they’re polluting more than they need to.

But we all use electricity, she cautioned. How do you get around that? Carolyn told me she doesn’t have enough money for solar panels, for instance, even though she’d like to have them.

I was surprised by the frankness of her response.

Sitting there, looking a grieving mother in the eyes, I felt complicit in Stacy’s death. I fly. I drive. I have an air conditioner. I felt guilty hopping a plane back home to Atlanta. It’s true that individual actions – eating beef instead of chicken, driving instead of biking, etc. – do matter. There are ways you and I can reduce our carbon footprints and global-warming complicity.

It would be wrongheaded, however, to blame only individuals for this crisis – and for Stacy’s death. Governments and fossil fuel companies hold the power to change.

In many parts of the United States, it would be difficult – and expensive – to choose clean, renewable energy over polluting fuels like coal and natural gas. There’s little reason for this. Iowa gets nearly 37% of its electricity from the wind. Carbon taxes and other policy tools would go further still, creating economic incentives for companies and citizens to do the right thing. It’s a common misconception there’s no solution to the climate crisis.

We know what to do. We lack the political will to do it.

The Trump administration continues to deny basic facts about the climate change crisis. In May, President Donald Trump threw a middle finger to the planet – and the future – by pledging to withdraw the United States from the Paris Agreement on climate change, which aims to limit dangerous warming to at most 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. Yet few of the countries participating in that agreement are doing enough, either. To avoid the worst of global warming, the world needs to be carbon neutral – no net carbon pollution – by midcentury, according to the latest research.

We often fail to reckon with the scale of change that’s required.

And we don’t face the full consequences of inaction.

We pretend global warming is no big deal, a distant threat.

We don’t look grieving mothers in the face.

Carolyn has dreamed about Stacy often this year. In her dreams, she and Stacy are doing the things they always did together : shopping, playing Bingo, talking about football, which was Stacy’s favorite sport. “Some people thought we were sisters,” Carolyn told me. “If you see me, you see her. If you see her, you see me. We were together” all the time.

But in the dreams, one detail has changed.

“I see her body,” Carolyn said, “but I can never see her face.”

She doesn’t quite know what it means.

Why isn’t Stacy all there?

Where did that vital part of her go?

No answer is enough to bring her daughter back.