Story highlights

Amid opioid epidemic, the Ohio criminal justice system has undergone a transformation

Local officers and judges now have to think like medical professionals

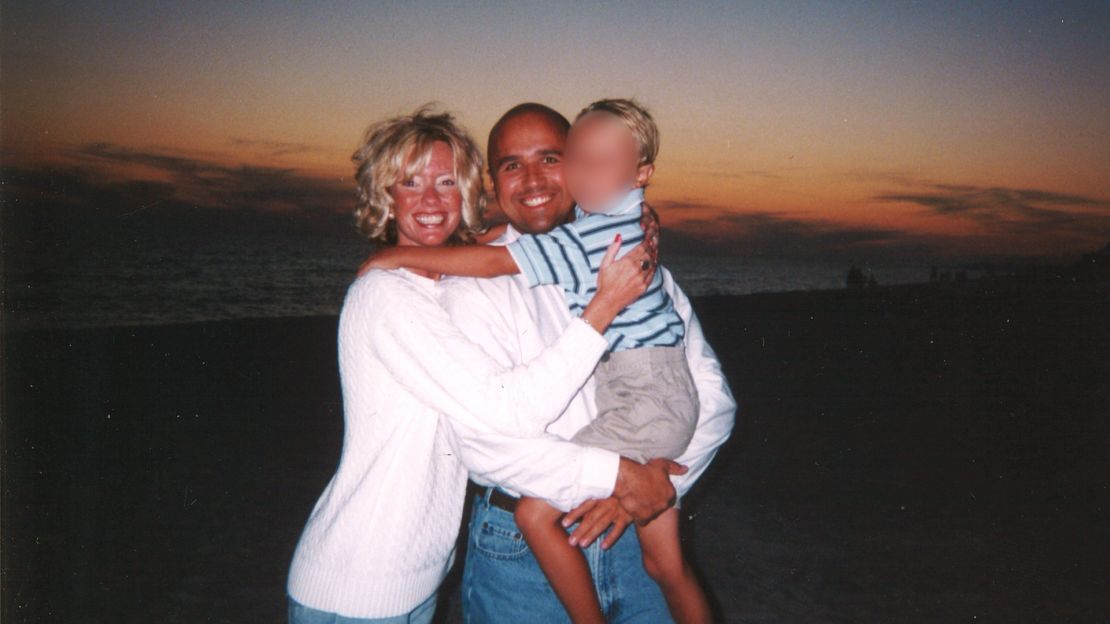

Robert Leahy was sitting on his couch, watching TV, when his wife,Gretchen, walked through the front door.

It was about 10 p.m. She’d left for the grocery store hours earlier. Now, she “bumbled” about the room, Leahy says, incoherent and vacant. He’d seen her like this before.

“What the f**k are you doing?” he asked. “You’re high.”

After the initial shock wore off, Leahy was angry and embarrassed. He worried about his reputation and what his colleagues at the Clermont County Sheriff’s Office would think. He’d been a law enforcement officer for more than a decade, and now he was married to a heroin addict.

He needed to save himself and their young son. He had done all he could to save her.

Just weeks earlier, Gretchen had returned home to Madeira, Ohio, from Crossroads Centre Antigua, an addiction treatment facility founded by musician Eric Clapton. It was one of a handful of times she’d received treatment for opiate addiction in the past five years. Leahy says he spent more than $16,000 – nearly all of their life savings – to cover the cost.

And now she was high again.

On September 7, 2005, Leahy filed for divorce and a temporary restraining order. At the time, the US opioid epidemic was in its early stages. Abuse of prescription painkillers was a growing, if hidden, problem, and heroin addiction had yet to ravage rural and suburban America. That would soon change. Nearly 15,000 Americans – 500 from Ohio alone – died of an opioid overdose in 2005. In 2015, those numbers soared to 33,000 and 2,700 deaths, respectively.

At first, Leahy could not understand why his wife had let herself become an addict, why she had made that choice. But as he watched her struggle for years to stay clean, his knowledge of addiction matured. He began to see it as a disease in need of treatment and compassion.

More than a decade later, as Ohio grapples with one of the deadliest drug epidemics in American history, the state’s criminal justice system has undergone a similar transformation. Local officers and judges know that they can no longer treat all addicts like criminals. To stop an epidemic, they have to think like medical professionals.

‘This is a mass fatality crisis’

On July 31, the White House’s Commission on Combating Drug Addiction and the Opioid Crisis released an interim report asking President Donald Trump to declare the opioid epidemic a national health emergency.

Ohio has been one of the states hit hardest by the crisis. Last year, 86% of overdose deaths in the state involved an opioid. In Montgomery County, the situation is particularly dire. Local officials say that more than 800 people will probably die from an opiate overdose there this year, more than double last year’s record of 349 opioid deaths.

Law enforcement officials say the county’s location has made it an ideal distribution hub for Mexican drug cartels. Interstates 70 and 75, two major arteries that crisscross the nation, intersect in the northeast corner of the region. Officials say the cartels ship their product directly to Dayton, less than a 10-minute drive from the intersection. Then, local dealers hop onto one of the “heroin highways” and circulate opioids throughout the country.

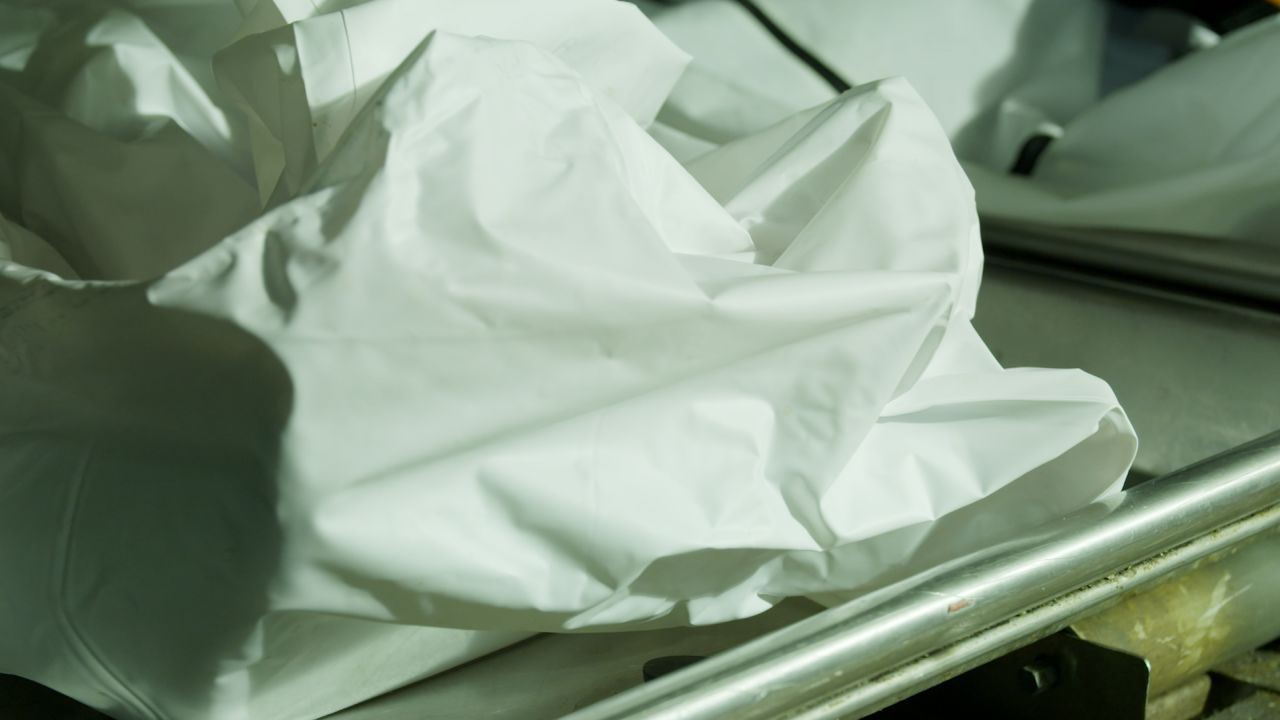

Most nights, the freezer in Montgomery County’s morgue is stacked floor-to-ceiling with bodies. Dr. Kent Harshbarger, the coroner whose office services more than 30 counties, estimates that 60% to 70% of these corpses are the result of an opioid overdose.

“What’s most challenging is seeing the same story repeated over and over again,” he said. “It seems, from my perspective, inevitable.”

Since last year, to deal with the surge in overdose deaths, Harshbarger has hired six part-time coroners, two autopsy technicians and three field investigators. He also extended some of the staff’s workday by three hours so they had time to perform more autopsies and remodeled the morgue freezer to fit more bodies.

Several times in 2015 and 2016, the office was overwhelmed, and he had to house some of the corpses in mobile morgues – trucks with refrigerated trailers. The state purchased the trucks in the mid-2000s with a grant from the Department of Homeland Security. They were intended to be used in the field to store bodies after a mass-casualty event like a plane crash or a terrorist attack. Harshbarger says the current crisis is not so different.

“Staff is overwhelmed,” he said. “This is a mass fatality crisis.”

What started as a heroin epidemic quickly turned even deadlier. Experts say the spike in overdose deaths in Montgomery, and in many places across the country, is largely due to heroin’s opiate cousins: fentanyl and its more potent analogues like carfentanil. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid 50 to 100 times stronger than heroin. Carfentanil, originally designed as a large-animal tranquilizer, is 5,000 times more potent than heroin.

Montgomery County Sheriff Phil Plummer says that when addicts think they’re purchasing heroin, they’re more likely buying one of these synthetic opioids.

“We need to quit calling it a heroin epidemic; this is fentanyl.” he said. “It’s really not a heroin issue anymore.”

The numbers back him up. In 2016, 251 of the 349 opioid-related overdose deaths in the county involved only fentanyl or carfentanil, with no heroin present, and an additional 34 involved heroin laced with fentanyl.

To stem the tide of overdose deaths, the sheriff’s office is spearheading a new program called Get Recovery Options Working, or GROW. As part of the initiative, a sheriff’s deputy, a social worker, a medic and a member of the clergy visit a home where an overdose occurred within the past week. Together, they provide literature about Cornerstone Project, a local drug treatment facility, and talk to family members about how to best help their loved one, and if the individual is willing, the deputy will drive him or her to treatment that day.

“We just stop and tell them, ‘We love you and we care for you, we want to seek help for you,’” Sheriff Plummer said. “And we’re having tremendous success with that.”

Since the program started on January 1, GROW has reached out to 162 people who have overdosed, 57 of whom have entered treatment at Cornerstone Project, Plummer says. More than half of those who entered Cornerstone because of the initiative are still in treatment, says Cornerstone Project Community Outreach Manager Wendie Jackson.

A stopgap

By 2014, Leahy had climbed the ranks to chief deputy in the Clermont County Sheriff’s Office. That year, drug overdose deaths were also steadily climbing in the county, from 56 in 2013 to 68 by year’s end. It was the sixth year in a row the number of overdose deaths had risen.

Leahy recognized the trend and had an idea. He’d heard about law enforcement agencies in other parts of the country equipping their officers with a drug called naloxone, also known by the brand name Narcan. Administered as a nasal spray, the drug could reverse the effects of an opioid overdose and was easy to use. Leahy lobbied Sheriff A.J. “Tim” Rodenberg and volunteered to lead the initiative.

Rodenberg, Leahy says, was receptive but not convinced. He needed more information. The topic would be controversial, he told Leahy. Some in the community would, of course, think it’s a good idea, but others would consider it a waste of taxpayer money.

Leahy called other sheriff’s offices in the north of the state that were using Narcan and learned about the success they were having in saving lives.

He told Rodenberg what he’d heard and laid out the pros and cons of buying Narcan. Then, Leahy decided to speak from personal experience. He didn’t bring up Gretchen by name, but “I think he realized some of the decisions that I made, or the things I pushed along, were related to that.”

Leahy and Gretchen still shared custody of their son, but he says she was rarely around. She would stay clean for a few weeks – periods he calls “flashes of brilliance.” Each time, he hoped she’d turned a corner. But really, he was just waiting for her to relapse. If she overdosed, he would want the responding officer to have all the tools available to revive her, so she’d have the chance to fight another day.

“How can you get people into recovery if you can’t save their lives?” Leahy asked Rodenberg. Within months, the deputies were equipped with Narcan.

‘The challenge is to keep them alive’

In Montgomery County, the average opioid user is a 38-year-old white man, according to data collected by the sheriff’s office. But officials say the number of young addicts in the area has increased exponentially over the past five years.

County Juvenile Court Judge Anthony Capizzi estimates that nearly a quarter of the young defendants in his courtroom are addicted to either opiate painkillers or heroin.

“I have jurisdiction over children until they reach 21,” Capizzi said. “The challenge for me right now is to keep them alive that long.”

Capizzi presides over the county’s Juvenile Treatment Court. The young people in his courtroom have substance abuse issues and often, as a result, lengthy criminal histories. Capizzi puts the vast majority into some kind of treatment program; detention centers are the last resort.

Three and a half years ago, Rachel Chaffin walked into Capizzi’s courtroom. She was one of the first young defendants addicted to heroin that he’d seen in his 13 years behind the bench in Montgomery.

Chaffin was 15 years old. She had been captain of the JV cheerleading squad in high school and dreamed of one day cheering on the sidelines for the Dallas Cowboys. But growing up, her life was chaotic and unstable. Her family often teetered on the edge of homelessness. In December 2013, Chaffin got pregnant.

“I was 14. I was freaking out,” she said. “I ended up having a miscarriage.”

A drug dealer in her neighborhood later asked her whether she wanted to be a “tester” for his product and check the quality of the dope. She was scared but took the leap, fueled by a depression that consumed her after her miscarriage.

“Once I started doing it,” she said, “I didn’t want to stop.”

She landed in front of Capizzi after multiple felony and misdemeanor charges. Eventually, the judge removed her from her mother’s custody because she continued to use and put her in foster care. For the next three years, she bounced from group home to foster home, sometimes clean, sometimes not. She overdosed, and was revived by Narcan, three times.

Now 18, Chaffin eventually found a good foster home and graduated high school with a 4.0 GPA. She says she’s been clean since March, when she relapsed after another miscarriage. She says she struggles every day to stay clean, but when she feels weak, she remembers what a counselor told her during a recent stay in rehab.

“My counselor said, ‘I want you to picture your mom coming to the morgue to identify your body,’” she said. “That just broke me. I can’t picture putting my mom through so much.”

Before there’s no hope

In 2013, the Clermont County Sheriff’s Office collaborated with local mental health officials to open the Community Alternative Sentencing Center inside the local jail. The voluntary program offers people who have been convicted of a misdemeanor and have a substance abuse issue the opportunity to serve their sentences in a wing of the jail that is separated from the general population. Nearly 40% of the participants at any given time were once addicted to opioids.

The center is operated by Greater Cincinnati Behavior Health Services. The participants – or “clients,” as staff refer to them – receive group therapy and drug rehabilitation treatment, such as participating in Narcotics Anonymous.

In 2016, the voters of Clermont County elected Leahy sheriff. He says he never had aspirations for the position, but in 2015, Rodenberg told Leahy he was retiring and wanted Leahy to be his successor. Leahy ran unopposed. Now, he was in charge of a program he’d help shepherd for years.

Alternative Sentencing Center clients technically are not inmates, and there are no correctional officers in that wing of the jail. The clients are on probation, and as part of that, they’ve agreed to complete their treatment. But if a client leaves the program early, he is in violation of his probation.

Leahy says these programs can help people before they’re burglarizing homes or robbing people to feed their habit – before they’re burdened with a rap sheet full of felonies. Once a person reaches that point, they often believe there’s no hope. Leahy saw Gretchen fall into a similar abyss, and it took her years to claw her way out.

“If you can catch people in the early stages, where their life is starting to go south but it’s not totally out of control,” he said, “there’s a chance for them.”

He doesn’t want people to mistake his compassion for weakness. Those who commit felonies, he says, deserve to be in jail. But most people with substance abuse issues are better served in treatment, he says.

So far, the program has helped men exclusively, but in the fall, Leahy and GCBHS will open a women’s version in another wing of the jail. The Clermont jail now houses between 90 and 100 female inmates, nearly double the number a decade ago, Leahy says. Virtually the entire increase in population, he says, can be attributed to the crisis. Opioid overdoses have increased 2000% in Clermont County since 2007.

Both the Narcan and Alternative Sentencing Center programs seem to be paying off. Overdose deaths in Clermont County decreased from 94 in 2015 to 83 in 2016.

“Is it too early to tell? Well, I think by the end of 2017, if we can get two or three years in a row with those numbers trending down,” Leahy said, “I think people will realize and say, ‘I think somebody’s doing something that’s working.’ “

Leahy says he speaks with Gretchen only occasionally now. There’s no ill will, but since their son has grown, there’s also no need. Gretchen says she’s been sober for three years, and Leahy gives her the benefit of the doubt. Not that he would ever ask. She doesn’t owe him any explanation, he says.

In some ways, he has a more clear-eyed view of her disease than even she does. Gretchen is still wracked with guilt from the years lost with their son and for driving her husband away.

“I think that was half of my issue. Every time I would get clean, I couldn’t let go of that guilt, shame,” she said. “And I still struggle with that to this day.”

But Leahy sees it differently. He says that the programs weren’t in place to save her, that law enforcement didn’t understand what they were dealing with yet. He’s learned that the addiction chose her, not the other way around.

“There is no rhyme or reason,” he says. “This is one of those deals, it’s kind of like fighting cancer. Your first heaviest, hardest hit is going to give you the best opportunity.”