Editor’s Note: Julian Zelizer, a history and public affairs professor at Princeton University and a CNN political analyst, is the author of “The Fierce Urgency of Now: Lyndon Johnson, Congress, and the Battle for the Great Society.” He’s co-host of the “Politics & Polls” podcast. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his own.

Story highlights

Julian Zelizer: On July 12, 1967, riots erupted in Newark, New Jersey, after an African-American man was pulled over and beaten by two white policemen

The fiftieth anniversary of the riots is a reminder that we still face some of the same issues of racism in policing and criminal justice, writes Zelizer

On the hot summer night on of July 12, 1967, two white policemen in Newark, New Jersey, arrested an African-American cabdriver named John Smith for “tailgating” and driving in the wrong direction. The police also accused Smith of physical assault and using offensive language. Race relations had been growing more tense over the year as Newark Mayor Hugh Addonizio announced a series of decisions that had angered the African-American community.

Some of the residents who were living across the street from where the arrest took place walked out of their homes to watch the incident. Smith was badly beaten. As the police hauled him to the Fourth Precinct station, word spread within the community about what was happening. African-American taxi drivers sent out reports through their radios. A crowd slowly gathered to monitor and protest Smith’s treatment. Word quickly spread about the arrest and what was taking place inside the station.

Violence later erupted in the city and in other cities in the United States, leading to a nationwide debate over policing, race relations, and urban decay that culminated with the release of the historic Kerner Commission Report, which declared that America was moving toward “two societies, one white, one black – separate and unequal.”

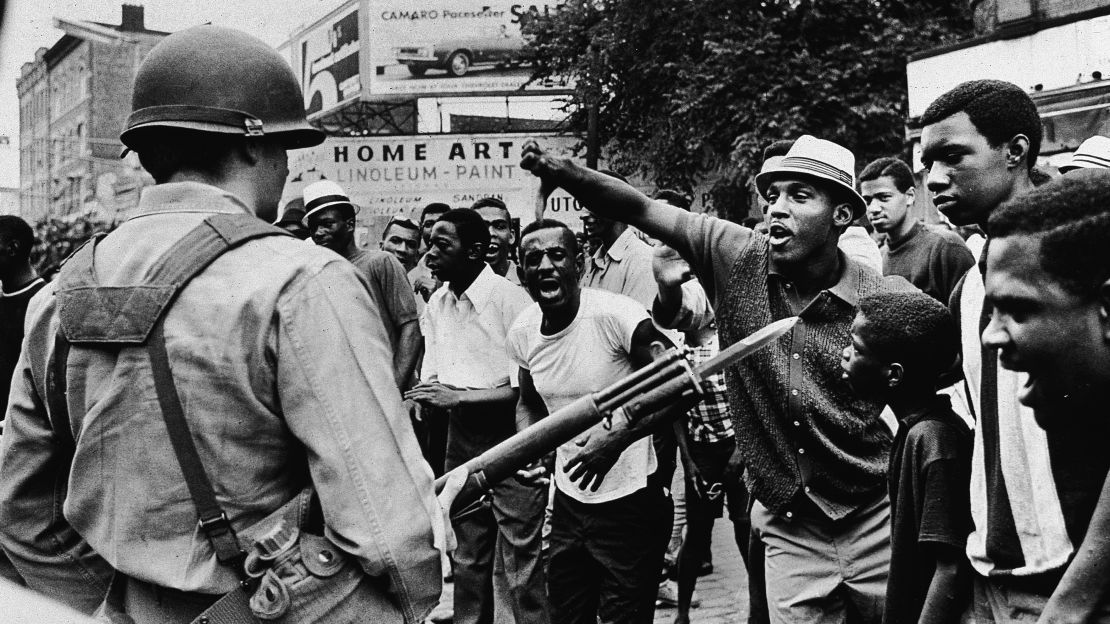

A total of five days of brutal rioting rocked Newark. There were violent clashes between the rioters and the National Guard, who were instructed to use their weapons whenever necessary. One African American man recalled that, as a child living through the riots, “my mother was so afraid, because she has eight kids, she had us under the bed hiding. I remember bullets and stuff coming through.”

A member of the National Guard remembered witnessing a fellow guardsman shoot a teenager who had stolen cigarettes, and his fellow guardsmen assaulting an African-American who was handcuffed. “It was just like the Wild West,” he said.

When the riots ended on July 17, there were 26 people dead and hundreds injured. But this was not the end of chaos for the country. The riots in Newark were followed by equally devastating riots in Detroit and several other smaller cities across the nation.

On July 23, undercover police in Detroit raided an unlicensed bar where a crowd of working class African-Americans had gathered to welcome home some returning Vietnam War veterans. The raid sparked five days of rioting. After the police rounded up 82 people, a crowd surrounded the police and yelled: “Black power. Don’t let them take our people away.”

Violence quickly escalated as the officers took the men to jail, and President Johnson signed an order authorizing federal troops to intervene. Forty-three people died, more than a thousand were injured; about seven thousand were arrested.

When the Detroit riots ended, the nation was stunned by what had occurred in this turbulent month. The promise of civil rights progress seemed to have fallen apart.

Soon after the Kerner Commission produced its shocking report, Richard Nixon was elected President and national politics moved in a more conservative direction. Rather than focusing on reforming our criminal justice system to achieve racial justice, the nation focused on President Nixon’s call to “law and order”– which entailed more punitive policies and sentencing, the militarization of local police forces, and the expansion of the carceral system.

The fiftieth anniversary of these riots is a troubling reminder of the distance that we have not traveled as a nation since the 1960s. Some of the same problems that were evident when violence shook the streets of Newark remain with us today.

It would be wrong to say that the nation has not made any improvements since July of 1967. There have been reforms to policing, public attitudes about race have changed, and the growth of African-American representation has changed the political dynamics surrounding these issues.

In recent years, these issues received renewed attention when citizens used their smartphones to capture videos of police engaging in violent and lethal behavior against African-American men. The videos spawned the most robust civil rights movement that we have seen in decades with Black Lives Matter, which put criminal justice front and center on the national agenda. Toward the end of President Obama’s term there was even evidence that a bipartisan coalition was taking form to push for legislation addressing this problem.

But after the movement built momentum, national politics once again moved in a different direction with the election of President Trump. The problems exposed with the images from Ferguson, Staten Island, Cincinnati and elsewhere have not been addressed. The recent court decisions that freed several police officers involved in the shooting of African-Americans offered further evidence for many civil rights advocates that the final years of the Obama presidency did not bring as much progress as they hoped they would.

Like Richard Nixon, President Trump pushed the national debate about policing in a very different direction. He expressed little sympathy for civil rights advocates and has been vocal about the need to provide full and unquestioning support for existing police and carceral institutions. There is little evidence that reform efforts at the local level are making any headway, either, as was evident with the recent decisions on police incidents that occurred.

As a result, we still live with many of the conditions that afflicted African-Americans fifty years ago. The Kerner Commission warned that if we did not take action the situation would only deteriorate and anger would continue to explode into violence. Policymakers and elected officials might want to take a look back at what the report had to say about the outbursts in Newark and Detroit, for their findings are still extremely relevant in our current era.