A crowd hovered over the man lying on the grass as his skin turned purple. Chera Kowalski crouched next to his limp body, a small syringe in her gloved hand.

Squeeze.

The antidote filled the man’s nostril.

The purple faded. Then it came back. Kowalski’s heart raced.

“We only gave him one, and he needs another!” she called to a security guard in McPherson Square Park, a tranquil patch of green in one of this city’s roughest neighborhoods.

“He’s dying,” said a bystander, piling on as tension mounted around lunchtime one recent weekday.

“Where is the ambulance?” a woman begged.

Squeeze.

Kowalski dropped the second syringe and put her palm on the man’s sternum.

Knead. Knead. Knead.

Nothing.

She switched to knuckles.

Knead. Knead. Knead.

Then a sound, like a breath. The heroin and methamphetamine overdose that had gripped the man’s body started to succumb to Kowalski’s double hit of Narcan.

With help, the man, named Jay, sat up. Paramedics arrived with oxygen and more meds.

Death, held at bay, again.

Kowalski headed back across the park, toward the century-old, cream-colored building where she works.

“She’s not a paramedic,” the guard, Sterling Davis, said later. “She’s just a teen-adult librarian – and saved six people since April. That’s a lot for a librarian.”

Libraries and a public health disaster

Long viewed as guardians of safe spaces for children, library staff members like Kowalski have begun taking on the role of first responder in drug overdoses. In at least three major cities – Philadelphia, Denver and San Francisco – library employees now know, or are set to learn, how to use the drug naloxone, usually known by its brand name Narcan, to help reverse overdoses.

Their training tracks with the disastrous national rise in opioid use and an apparent uptick of overdoses in libraries, which often serve as daytime havens for homeless people and hubs of services in impoverished communities.

In the past two years, libraries in Denver, San Francisco, suburban Chicago and Reading, Pennsylvania have become the site of fatal overdoses.

“We have to figure out quickly the critical steps that people have to take so we can be partners in the solution of this problem,” Julie Todaro, president of the American Library Association, told CNN.

Related Stories

Though standards vary by community, the group is crafting a guide for “the role of the library in stepping in on this opiate addiction,” she said. It will include how to recognize opioid use – short of seeing someone with a needle – and how to address it.

McPherson Square Library, where Kowalski works, has a wide, welcoming staircase punctuated by tall columns. It sits in the Kensington community, where drugs and poverty lace daily life.

Residents drop into the McPherson branch with questions about doctor visits and legal matters. Children eat meals provided by library staff and play with water rockets in a Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics program.

Kensington doesn’t host a civic institution, like a university, or a major company, said Casey O’Donnell, CEO of Impact Services, a Kensington community and economic development nonprofit.

“In the absence of those things, the anchors become things like the library,” he said.

In recent months, so-called “drug tourists” – people who travel from as far as Detroit and Wisconsin seeking heroin – started showing up in Kensington, which boasts perhaps the purest heroin on the East Coast, library staff and authorities said.

Heroin userscamped out in McPherson Square Park and shot up in the library’s bathroom, where nearly a half-dozen peopleoverdosed over the past 18 months, said branch manager and children’slibrarian Judith Moore.

The problem got so bad that the library was forced to close for three days last summer because needles clogged its sewer system, said Marion Parkinson, who oversees McPherson and other libraries in North Philadelphia.

Since then, patrons have had to show ID to use the bathroom, she said. The library in October hired monitors to sit near the bathroom, record names on a log and enforce a five-minute time limit.

Before the crackdown, library staff last spring discovered one man in the bathroom with a needle in his arm, Moore recalled. He toppled over and started convulsing.

“I heard his head hit the floor,” she said.

A city employee had left a dose of Narcan at the library. But the staff didn’t know how to use it. After that, Parkinson set out to get them trained.

‘It’s not normal’

At 33 years old, Kowalski wears oversized sweaters and too-big glasses. She reads nonfiction about World War II and zones out on Netflix. She settles into work mode by listening to pop music on her train ride to work.

She chose to work at the McPherson branch because she thought her own experience could help students who flock there after school.

Kowalski’s parents used to use heroin. They’ve been clean for more than 20 years. Her mother earned a college degree in her 50s; and her father, a Vietnam veteran, worked steadily as a truck driver until retiring, she said.

But before all that, Kowalski lived in the turmoil of addiction. “I understand the things the kids are seeing. … It’s not normal,” she said of her library charges. “It’s unfortunately their normal.”

Now, when a drug user overdoses at or near the McPherson library branch, Kowalski takes a minute to “switch the headset” from librarian to medic, she said.

When she got word that recent day that Jay had collapsed in the grass, Kowalski reached into a circulation desk drawer and pulled out a blue zipper pouch containing Narcan and the plastic components required to deliver it.

Dashing out of the library, she asked if anyone had called 911. Someone had.

The librarian got to Jay, crouched down, noticed his shallow breathing and discoloration.

She tried to focus. Seconds ticked. Prepping Narcan takes four steps: unscrew the vial, put it in the syringe, screw on the nasal mister, squeeze out the medicine.

“You’re under a time limit,” she recalled. “It’s how fast can I do this.”

Kowalski recognized Jay’s face from the neighborhood. As she walked away from him, she felt relief. He would live.

“I understand where they’re coming from and why they’re doing it,” she said of heroin users. “I just keep faith and hope that one day they get the chance and the opportunity to get clean. A lot of things have to line up perfectly for people to enter recovery long-term.”

Back at the library, Kowalski tried to refocus. The phone rang. Just minutes earlier, she’d pulled Jay back from the edge. Now, she was helping a patron find the number for the US Treasury Department.

‘We want our libraries to be safe’

When a man overdosed in late February in the bathroom at Denver Central Library, security manager Bob Knowles rushed to his aid.

Just hours earlier, the branch had received its very first delivery of Narcan, which library workers sought after a fatal overdose earlier that month at their branch.

Knowles, the inaugural hero of his team’s effort to stem the opioid scourge, lost a brother 40 years ago to an overdose.

“I wish somebody had had Narcan for him,” Knowles said.

Security staff, social workers and peer navigators — former drug users who help current ones — all learned to administer the overdose-reversal drug. The fact that it got used the day the first shipment arrived confirmed “we were on the right path,” said Chris Henning, director of community relations for the Denver Central Library.

The branch is near Civic Center Park, a haven for homeless people and a market for street drugs. One recent morning, a self-described drug addict who prefers methamphetamine and the synthetic drug “spice” camped out near the library.

Staff members at other Denver library branches are now also being trained to deliver the medicine, library officials said, adding that they’ve gotten calls about their regimen from libraries in Seattle, small Colorado mountain towns and parts of Canada.

Meantime, a fatal overdose in February at a San Francisco library branch pushed officials there to forge ahead with Narcan training for security officers, social workers and employees who help the homeless, said Michelle Jeffers, a library spokeswoman.

“We want our libraries to be safe for all visitors,” she said.

Crisis in Philadelphia

Drug overdoses nationwide more than tripled from 1999 to 2015. Opioid overdoses accounted for 63 percent of the 52,000 fatal cases in 2015 – or about 33,000 people, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported. Across the country, 91 Americans die every day from an opioid overdose.

Philadelphia last year saw about 900 fatal overdoses, up nearly 30% from 2015, municipal tallies show. Nearly half the deaths involved fentanyl, the powerful opioid that killed Prince. This year’s total could hit about 1,200 fatal overdoses, Drug Enforcement Agency Special Agent Patrick Trainor said.

Opioid Abuse: How to Help

“It is among the worst public health problems we’ve ever seen, and it’s continuing to get worse,” Philadelphia Health Commissioner Dr. Thomas Farley told CNN. “We have not seen the worst of it yet.”

Opioids attach themselves to the body’s natural opioid receptors, numbing pain and slowing breathing. They can relieve severe pain – but also can spur addiction. Almost 2 million Americans abused or were dependent on prescription opioids in 2014, according to the CDC.

Naloxone kicks opioids off the body’s receptors and can restart regular breathing. Hailed as a miracle remedy, the drug is squirted into the nose or injected into a muscle.

Harm-reduction groups and needle exchanges started distributing naloxone two decades ago, and since then, more than 26,000 overdoses have been reversed, the CDC reports.

The drug has become a staple for police, fire and medical professionals, who can buy it for $37.50 per dose. Retail pharmacies sell it over the counter. Coffee shop baristas have been trained to administer it.

Philadelphia Fire and EMS used Narcan last year about 4,200 times, mostly in the Kensington neighborhood, Capt. William Dixon said.

‘I might need to take a mental day’

Armed with Narcan, McPherson’s library employees keep an eye out for overdoses. When he spots one, Davis, the security guard, tries not to alert the children.

Kowalski’s first save in the park, back in April, happened when a young woman overdosed on a library bench after school. One dose of Narcan revived her: She got up and walked away.

But when Kowalski turned around, several kids – all library regulars – were standing on the steps watching.

“I got really upset because I know what they were seeing,” she said.

Weeks later, she revived a man who overdosed on fentanyl and fell off a bench in front of the library. “I might need to take a mental day tomorrow,” she told Moore afterward.

But then her library regulars arrived after school. She played games with them and helped them on the computer.

By the end of the day, “I felt good again,” Kowalski said. The next day, she was back at work.

In the square, once dubbed Needle Park, library volunteer Teddy Hackett uses a grabber to pick up needles in the grass, near benches and in the rose bushes.

“That’s my rose bush there,” he said one recent day. “I protect that rose bush.”

Hackett, who beat drug addiction almost 20 years ago, said he once got mad when he saw a man shooting up on a bench in front of the library. Hackett chased him away, the needle still stuck in his arm.

“God’s got me doing this for a reason,” he said, laughing. “For the little kids and the animals.”

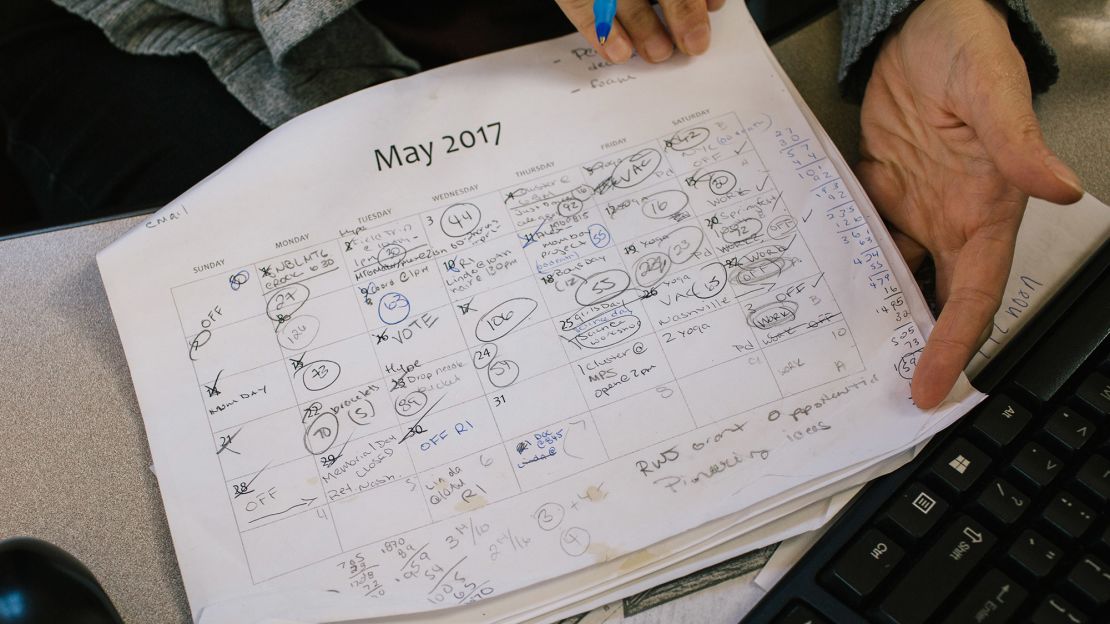

He reports his daily needle tallies to Kowalski. May set a record: 1,197 needles. The previous one, set last fall, was about 897.

The increase might reflect the spike in drug use. It also could mean a redevelopment surge in the city has pushed a long-lingering problem out of the shadows, said Elvis Rosado, the education and outreach coordinator at Prevention Point, a local nonprofit that trained Kowalski and more than 25 colleagues to use Narcan.

“They’ve been here for years,” Rosado said of drug users. “It’s just that they’ve been in abandoned buildings.”

As evidence of addiction has spread, Philadelphia leaders have stepped up to counter it. Mayor Jim Kenney formed a task force to tackle the opioid epidemic.

The city’s health department launched an ad campaign called “Don’t Take the Risk” to remind patients that a drug isn’t completely safe just because a doctor prescribes it. Officials mailed out more than 16,000 copies of the addiction warning.

In McPherson Square Park, clean-up projects, a new playground and lights have improved the grounds. Police in mid-June increased patrols there and plan to install a mobile command center, which will also offer social services.

‘Call Chera’

The day after Kowalski’s naloxone doses revived Jay, more drug users trickled into McPherson Square Park, where sirens whine like white noise. Nearby, a slender woman shot up heroin, then got up and walked away.

Moments later, a former freight train operator who weeks earlier had overdosed twice in one day, sat down on his cardboard blanket and overdosed again. He’d gotten hooked on prescription pills after a leg injury. A heroin user gave him Narcan that she’d bought from another user for $2.

An hour later, paramedics carried away a woman who’d overdosed while sitting on a bench, said Davis, the security guard.

“I’m pretty sure we’re going to get one or two more people that’s going to OD out here today,” he said.

An hour later, it happened: A woman who’d earlier been hanging out with the train operator slumped over on the ground.

Davis didn’t flinch. Standing at the library door, he told the needle collector to find Kowalski.

“Ted,” he yelled, “call Chera!”

CNN’s Sara Weisfeldt reported from Denver.