The protesters chant in English, then in Spanish, as they belt out their rallying cry.

“The people, united, will never be defeated!”

“El pueblo, unido, jamás será vencido!”

Winston-Salem’s leaders are hours away from deciding whether to declare this a “welcoming city” for immigrants. And at a rally on the steps of City Hall, supporters of the measure are making their case one last time.

“Now do it in Arabic!” someone shouts. Demonstrators cheer as a woman wearing a hijab approaches the microphone.

But then, everyone freezes. A counter-protester paces in front of them, briefly sending a chill through the crowd. Some people laugh. Others look stunned.

The woman is wearing a bright red T-shirt that says “TRUMP 2016.” She has a matching sparkly flower in her hair.

She doesn’t say anything. And she doesn’t have to. The hand-written cardboard signs she’s carrying make her message clear:

“President Trump says NO! Obey the Law!”

“A Sanctuary City is against the LAW of our land.”

Two views of the future

Valeria Rodriguez Cobos glares at the woman in the Trump T-shirt. She’s frustrated to see her getting so much attention, even though the woman is far outnumbered by pro-immigrant protesters.

Rodriguez Cobos has been coming here for months as part of a group of activists pushing for Winston-Salem to become a sanctuary city. The 25-year-old’s mission: using her voice for those who have none.

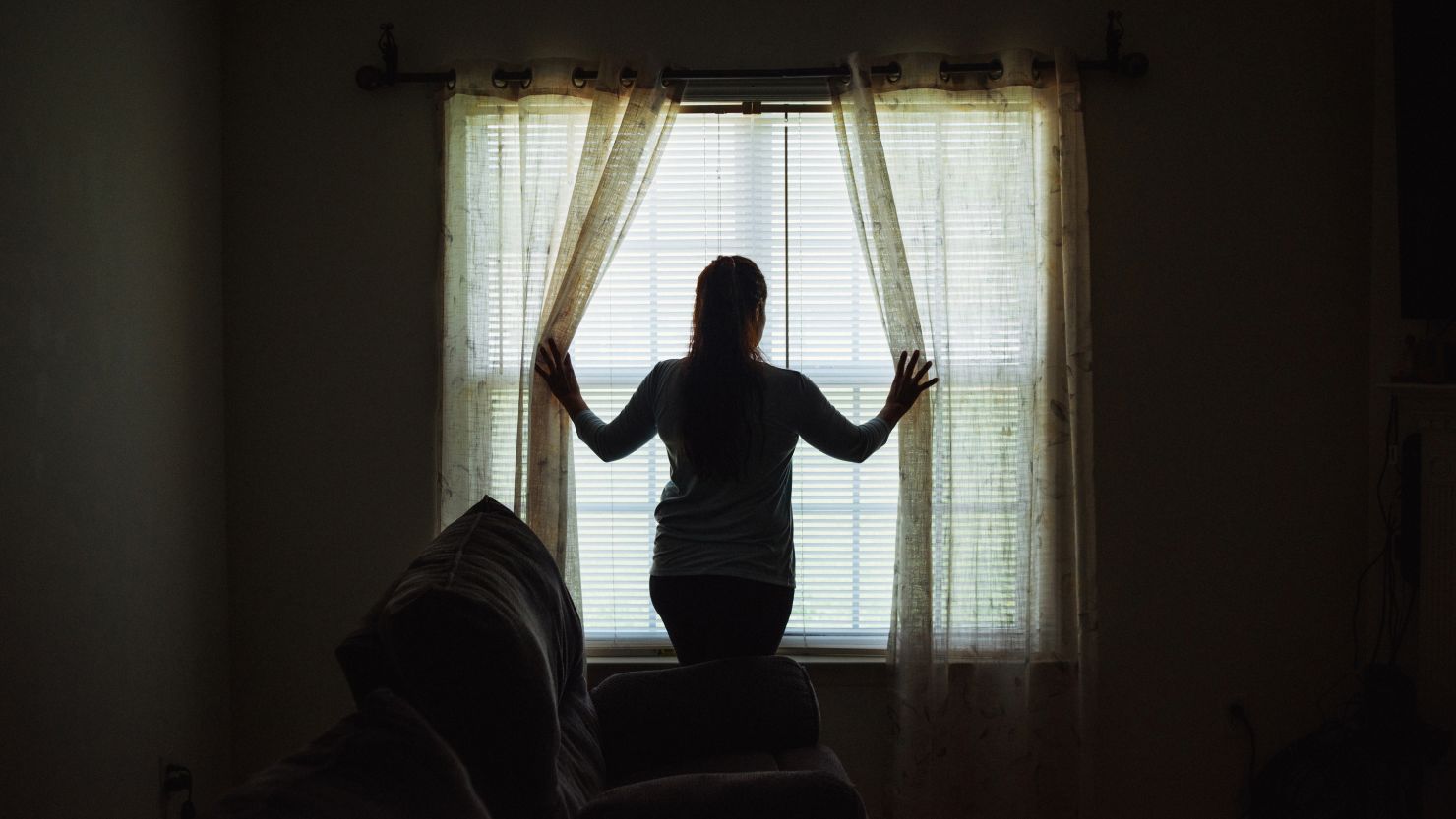

She has a green card, but most of her friends and family don’t. And as she stands on the steps of City Hall tonight, she knows she’s carrying the weight of thousands of people who need help, but aren’t here simply because they’re too scared to show up.

The neighbors who panicked when they saw a white van circling their apartment complex, terrified that ICE agents were about to swoop in. The children at her church who went running when police neared their playground. The friend who just asked her to take care of her kids if she gets deported.

The counter-protester winds her way into the building. A demonstrator waving a sign saying “HUMAN RIGHTS” follows close behind.

The crowd resumes chanting, louder than before.

From inside, Joan Fleming can hear them. And it’s making her uneasy.

She thinks back to riots she lived through as a child growing up in the 1960s. Her father was a police officer then. She thought of him as she came to City Hall today, carrying an American flag tote bag stuffed with petitions. He raised her to respect the importance of law and order.

Back then, when violence flared during protests, she’d wait by the door of her family’s home in Kinston, North Carolina. Every night she feared her father wouldn’t make it back alive.

Now as she sits inside the City Council’s meeting room, those fears have been replaced by new ones – growing concerns about what Fleming believes could be just around the corner, and what she feels is lurking in plain sight.

She’s already warned the City Council about what she fears will happen if they pass the “welcoming city” proposal: Felons will flock to Winston-Salem.

“There are thousands of chances per month for you or your loved one to be killed by a suspected illegal drunk driver,” she told officials at last month’s meeting.

Tonight she hopes they’ll remember what she said.

Echoes of a larger fight

This was the scene on Monday, April 17,in one corner of Winston-Salem, North Carolina, as a controversial vote loomed.

But it could be anywhere in America in 2017, as increasingly divisive debates over immigration expose feelings simmering beneath the surface.

President Donald Trump made cracking down on illegal immigration a focal point of his administration.

He took steps to retaliate against so-called sanctuary cities, vowing to cut off funding to local governments that don’t cooperate with the feds. He doubled down on his message that undocumented immigrants can be a danger to communities, creating an office focused on victims of immigrant crime.

Critics say Trump is highlighting crime as a pretext for plans to kick out as many undocumented immigrants as possible, regardless of whether they pose a threat.

Since he took office, immigration arrests are up and illegal border crossings are down. But so far, Trump also appears to be deporting fewer people than his predecessor.

It’s too soon to say whether these early numbers will translate into a trend.

But spend a day in this Southern city, where the salvos of national political battles echo loudly, and you’ll see signs of a deepening shift beyond what’s measured with statistics in spreadsheets.

Tensions are high. So are suspicions. And there’s one thing both sides have in common: fear.

Sending a message

At first, Dan Besse thought his resolution declaring Winston-Salem a welcoming city would sail to approval.

The city already prides itself on being a place that’s made immigrants feel at home. Industrial, manufacturing and construction jobs, plus a low cost of living, made Winston-Salem an attractive destination.

Now the city that once saw race as a matter of black and white is more than 15% Latino – the largest percentage in any major city in the state. More than 10% of its residents are immigrants. And the Pew Research Center estimates that about 25,000 undocumented immigrants live in the metro area, roughly 4% of the total population.

Besse is an attorney who’s been on Winston-Salem’s City Council since 2001. He thought his proposal wouldn’t rock the boat much because it wasn’t creating new rules or overturning any old ones. But he’d heard about mounting fears for immigrants in his city – about parents who were too scared to take their children to doctor’s appointments or leave them in after-school programs, about threats to local mosques.

And he wanted to send a symbolic message.

“A lot of folks don’t feel safe,” he said, “and they really need this kind of reassurance that their local elected representatives are on their side.”

So at a February meeting, Besse unveiled a resolution that he says intended to do just that. It was a compromise move that skirted the word “sanctuary” and some of the more controversial measures activists had proposed, such as a pledge to limit cooperation with federal law enforcement.

Among its proclamations: “Whereas, the current national environment of excessive fear and suspicion directed by some toward immigrants, refugees, and other newcomers calls for cities like Winston-Salem to reaffirm our commitment to providing a welcoming and inclusive community for all.”

In this left-leaning city with a City Council where seven of the eight members are Democrats, it was the kind of message that sounded like an easy sell.

Maybe a few years ago, or even a few months ago, it would have been.

Besse’s proposal cleared a committee and seemed to be gaining steam among his colleagues. But it wasn’t long before it sparked an uproar. First local Republicans rallied against it. Then state elected officials took aim.

At a meeting in Raleigh, they told Winston-Salem to bury the welcoming city measure or risk losing funding.

“There will be consequences if Winston-Salem does this,” one state senator warned.

‘Like a rattlesnake’

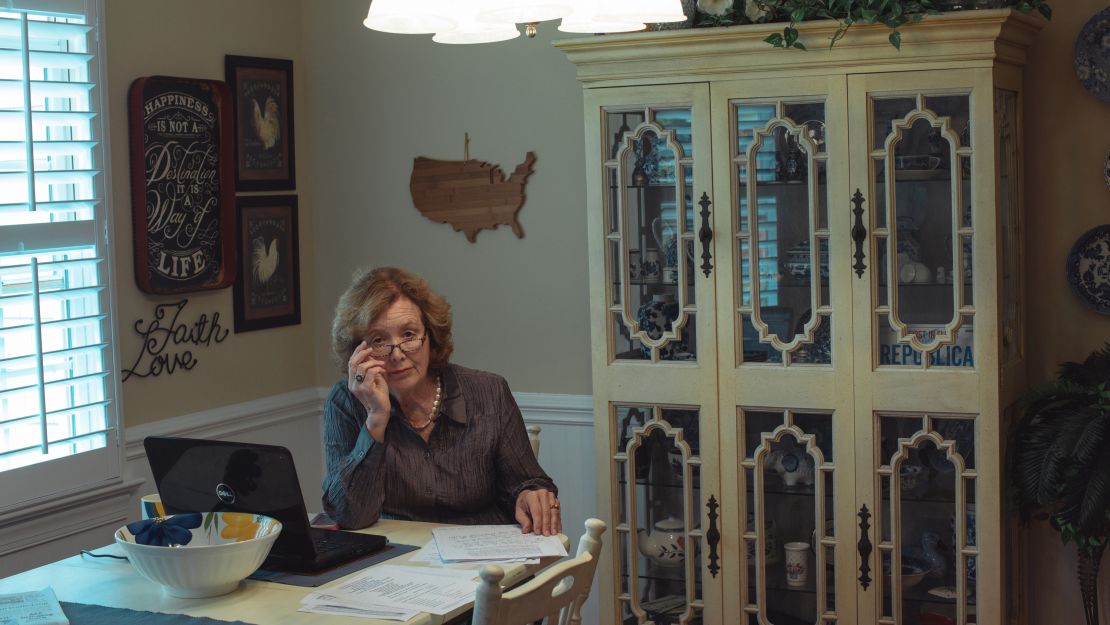

As she gets ready for the vote, Joan Fleming sits at her kitchen table, staring at her laptop screen.

A wood carving of the continental United States hangs behind her, near metal sculpted into cursive lettering that says “Faith” and “Love.”

A magnet on her refrigerator says, “Friends don’t let friends vote Democrat.”

The lifelong Republican is no stranger to rallying around a cause. Ever since she moved to Winston-Salem in 1990, she’s worked for candidates and campaigns, from Sen. Jesse Helms’ 1996 reelection battle to North Carolina’s 2012 amendment banning same-sex marriage. As she sits at her computer and prepares for a vote she’s very worried her side might lose, she glides her mouse across the elephant on her mousepad that says “Grand Old Party.”

Fleming’s phone rings. It’s someone she hopes will be at tonight’s meeting. And she wants to make sure they’ve signed her petition.

“I’ve put it on my Facebook about 2,500 times. If you haven’t seen it, you must be living under a rock,” she says. “I don’t know how to put it out there any other way.”

Beside her, she has copies of several recent arrest reports – proof, she says, that being too lax about illegal immigration is endangering people in the area.

Is it unfair to paint an entire group based on the most severe crimes committed by a handful of people? Fleming doesn’t think so. She suspects the amount of crime connected to illegal immigration is under-reported. And even one crime, she feels, is one crime too many.

“It’s a life. It’s a rape,” she says. “If we hadn’t been negligent in letting them in here, it wouldn’t have happened.”

She resents it when critics call her and others who oppose Winston-Salem’s proposed welcoming city measure hateful or racist. Fleming says there’s nothing hateful about supporting legal immigration and standing firmly against illegal immigration.

“I might like a rattlesnake,” she says, “but I don’t want them in my living room. I lock my doors at night.”

If she were a few years younger, Fleming, who’s in her 60s, says she’d head to the Mexican border and build the wall herself.

Collecting ammunition

Instead, Fleming is spending Monday afternoon on the road, driving around Winston-Salem’s suburbs as she picks up copies of petitions. The vote is only a few hours away, and she knows every signature counts.

She heads down a hilly country road, past grazing horses and Baptist churches and an apartment complex called Plantation Place, to collect a stack of papers left for her. The petitions are on top of a Buick parked in a carport with a “Make America Great Again” bumper sticker.

She stops in a Chick-fil-A parking lot near a strip mall to get another stack from a friend who’s fallen ill and won’t be able to make it to tonight’s meeting.

Fleming doesn’t live inside the city limits. Her home is about a 20-minute drive away, near a golf course in Advance, North Carolina. But most of her family lives in the city. And Fleming says anything that happens inside Winston-Salem will spread.

She’s heading to City Hall armed with a tote bag full of testimonials from others who share her views:

“I will no longer feel safe as a single female if this happens.”

“The safety of our city and our children is at stake.”

“Our city is being overrun with aliens. I notice my own neighborhood is being flooded with immigrants. … I don’t feel safe letting my grandchildren play outside unless I am with them. Not the America my children grew up in.”

Loud and clear

As they chant on the steps outside City Hall, the protesters are sending a very different message:

“No ban, no wall, sanctuary for all.”

“Fund educations, not deportations.”

“Say it loud, say it clear, immigrants are welcome here.”

“Hey ya’ll,” Valeria Rodriguez Cobos says into the microphone, smiling at the crowd.

Rodriguez Cobos was only a year and a half old when her parents brought her to the United States from their home in Oaxaca, Mexico. For 22 years, she was undocumented. Like many of her family members, she lived in the shadows, terrified that the life she was trying to build could dissolve in an instant.

But the 25-year-old is a permanent resident now. Several years ago she was able to petition for legal residency under the Violence Against Women Act after surviving an abusive relationship.

Today she’s wearing a black T-shirt with bold white letters on it that say, “free.”

Legal immigration status has brought some stability, but she says it’s impossible to feel secure when almost everyone you know is still at risk.

Rodriguez Cobos chokes up as she tells the crowd how privileged she feels to have a green card.

“It’s something I know my family still doesn’t have,” she says. “So for me, the fight is not over until we’re all safe.”

A woman who works with refugees describes the harrowing stories they’ve told her about what happened before they fled their homes. A Wake Forest law professor explains that there’s nothing illegal about the resolution the City Council is finally about to vote on. Besse tells the crowd that whatever happens to his resolution tonight doesn’t really matter.

The important thing, he says, is continuing community activism, standing up for what’s right and not letting lawmakers in Raleigh dictate the way the city handles its affairs.

“We cannot afford to capitulate to bullying tactics and intimidation, telling us not to speak up and out on behalf of those who are marginalized in our communities.”

Pointing toward home

Lori Apple watches from a few feet away, wearing a sparkling American flag lapel pin on her jean jacket. The protesters’ words quickly get under the 60-year-old physical therapist’s skin.

They seem to be fanning the flames of emotions, she says, rather than relying on facts.

Apple, the head of a local Republican women’s association, says the welcoming city resolution quickly drew fire from many people in her party.

It’s clear, she says, that the measure is a thinly veiled attempt to turn Winston-Salem into a sanctuary city. That’s extremely unwise, she says, given vows by Trump and Attorney General Jeff Sessions to yank federal funding from local jurisdictions that don’t cooperate with immigration enforcement efforts.

And it’s not just federal officials who are threatening to fight back against local measures, she says.

State lawmakers in North Carolina outlawed sanctuary cities back in 2015. Then-Gov. Pat McCrory signed the measure in nearby Greensboro. And now, legislators in Raleigh are weighing ways to punish local governments that take sanctuary steps.

But Apple says the concerns she and others share aren’t just about the millions of dollars Winston-Salem could stand to lose.

She says she’s worried about her family – about the spots they could lose in college, about extra time they could be stuck waiting in emergency rooms, about the ways crime could go up and terrorists could slip in.

“I have children and I am concerned with the safety of our community,” she says. “The loud voices of a few drown out the quiet voices of good, hard-working Americans who are not in favor of these kinds of measures.”

To sum up her views on immigration, Apple uses her three-bedroom house in Lewisville, about 15 minutes outside Winston-Salem, as a metaphor.

There are only so many items in the refrigerator to go around and only so many rooms in the house where there’s space to live, she says. And of course, she keeps the doors locked at night and takes other steps, she says, to protect against intruders.

Resources are scarce in America, Apple says. And the country needs to do what it can to keep out terrorists and keep its citizens safe.

That’s all the president and North Carolina’s state lawmakers are trying to do, she says.

“There’s a lot of anger among people towards Trump,” she says. “But he’s trying to protect us.”

‘I show them safety’

Across town, Carmen is just winding down her day cleaning houses.

The 43-year-old undocumented immigrant can’t make it to tonight’s meeting. But she’s been following news of the proposed “welcoming city” measure closely. And she’s hoping the city will pass it.

“It would be a safer city,” she says. “It would be a relief for us.”

Carmen, who asked to be identified only by her first name to protect her family’s safety, has trouble feeling safe these days.

She’s terrified that Trump will end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, putting her three children in jeopardy.

She’s afraid jobs for immigrant workers are going to dry up.

She’s scared to go out at night.

She senses people are giving her hostile glances in stores.

It wasn’t like this before, Carmen says. Trump, she says, has planted seeds of hatred across the country. But Carmen says she’s seen love blossoming, too. One day people from a nearby church left signs outside for her church’s largely immigrant congregation.

“Somos uno en Cristo.” We are one in Christ.

“Dios te ama.” God loves you.

“Nos encantan nuestros vecinos.” We love our neighbors.

Carmen was overjoyed. She snapped photos of her children with the signs and keeps them on her phone.

She’s afraid of what will happen next, but she doesn’t talk about it with her children.

“I show another face to them. I show them safety,” she says. “I don’t show them the fear I feel.”

A tense wait

Inside City Hall, Fleming is one of the first peopleto arrive in the City Council’s meeting room.

It’s already tense. There aren’t enough chairs. Some people whisper. Others glare suspiciously across the room.

Fleming settles on a spot in the middle of the third row, then moves to the other side of the room after a man snarls at her for trying to save a seat.

Rodriguez Cobos sits with a few friends on the floor of a room upstairs, their eyes trained on a TV screen.

So many people have shown up to tonight’s meeting that officials opened two overflow rooms to give them a chance to follow what’s happening.

Rodriguez Cobos’ friends are US citizens whose parents are undocumented immigrants, and they’re here to make their voices heard. But as they sit inside the imposing government building, Valeria can see that her friends are spooked.

She tries to explain what she knows about city government to them. In between her business administration classes at Salem College and her work at a local credit union, she’s been coming here regularly for months. The pomp and circumstance of a local government meeting is familiar now. The way the clerk reads out the name of each resolution. The way the council members make motions.

She wants her friends to feel like they belong here. This is their city, too, even though sometimes it may not feel like it.

As tonight’s vote nears, they lean in toward the TV to listen.

Caught off guard

There’s no fanfare as the clerk announces what’s next on the agenda: “Item G-4, Adoption of the ‘Winston-Salem is a Welcoming City’ Resolution.” This is the moment almost everyone in the building is waiting for.

But the mayor makes a surprise announcement that catches many of them off guard.

Besse, he says, has asked to withdraw the resolution from the night’s agenda.

“He’s working on an alternative thought,” the mayor tells the crowd.

Rodriguez Cobos and her friends can’t believe what they’re hearing. She wants to run screaming into the meeting room. How can this be happening?

Fleming feels frustrated too. Her rush to get signatures for a petition, her push to save seats inside for fellow Republicans who feel the same way she does – all of it seems like a waste of time.

A man rushes to the front of the room, yelling as he heads out the door: “Boo! Cowards!”

In the public comment period that ends the meeting, speaker after speaker slams the City Council for letting worries about retribution from state and federal officials stop them from taking a stand.

“What we heard today,” one woman says, “was fear.”

One man says the move sets a dangerous precedent. “If you allow them to bully you all, then who will they come for next?”

Another says he’s tired of hearing people focus on crimes committed by immigrants.

“There’s people who look like me who ran people over. There’s people who shot up schools who look like me. Should we deport all of them, too? Are we just going to use fear as our guiding principle?”

Rodriguez Cobos is the last person to speak. She says she and others won’t forget how the City Council backed down instead of standing up.

“Elections are coming up,” she says, “and people are paying attention.”

As Rodriguez Cobos walks to her car after the meeting, she looks over her shoulder.

She’s determined to keep speaking out, but she knows it makes her a target.

Fleming walks quickly to her car, too.

She fears crime is on the rise. And you never know who might be watching.

The next battle

Winston-Salem’s alt weekly doesn’t mince words in its headline summarizing the council’s move: “Unwelcoming City.”

But Besse maintains his proposal isn’t dead. Instead, he says he’s planning to bring it back in a different form. Pulling it from the agenda was a change in tactics, he says, but not a retreat.

When he realized the welcoming city resolution wouldn’t have enough support to pass, Besse says he withdrew the measureto avoid sending the wrong signal.

These days, he’s carrying a copy of a new document inside his jacket pocket as he walks around Winston-Salem. He’s hoping to convince leaders from across the community to sign on.

A joint statement from a broader group touting the city’s welcoming nature, he says, will send a stronger message than any City Council resolution would.

Rodriguez Cobos and other organizers with the Sanctuary City Coalition of Winston-Salem say their fight has only just begun. They’ll be marching in an upcoming “day without immigrants” protest.

And they’re hoping to take more concrete steps to help protect an immigrant community under siege. One idea: emergency response teams that can report to areas where ICE arrests are taking place.

Fleming says she’s keeping a close eye on the City Council in case the welcoming city measure comes up again.

And she’s going to keep canvasing for signatures on her petition opposing it.

She’s also working on promoting the local Republican women’s club’s next activity: a self-defense class.

A family crisis

At a church Bible study meeting in northern Winston-Salem, Carmen is looking for answers.

The City Council meeting was a few days ago. She’s still hoping officials will change their mind, and she wishes she’d been at City Hall to see what happened. She went once and loved the part where everyone stood together to say the Pledge of Allegiance.

But this week, she’s barely had any time to spare. She’s overwhelmed with a crisis that’s shaken her family.

Her brother is in a detention center and could be days away from deportation.

His devastated 10-year-old daughter is barely talking or eating. All she does is cry. They’re taking her to a psychologist, but Carmen doesn’t know what else to do as she waits for word on whether officials will reopen her brother’s case.

“I’m so worried,” she tells the church group, tears streaming down her face.

The pastor offers a prayer for Carmen and others at the table.

“God, we put our worries and our anguish in front of you. … Touch the hearts of the authorities in this country,” he says. “Touch the hardened hearts that they seem to have right now.”

Carmen bows her head.

She prays for something she fears only God can give her now.

Protection.

CNN’s Theresa Waldrop and Janette Gagnon contributed to this report.