Story highlights

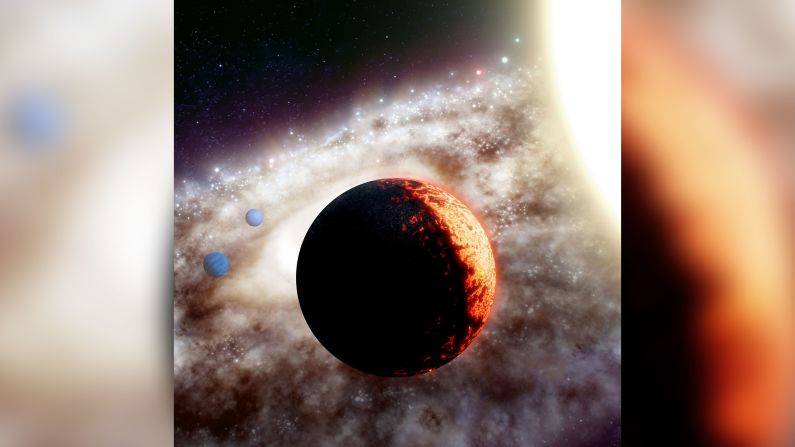

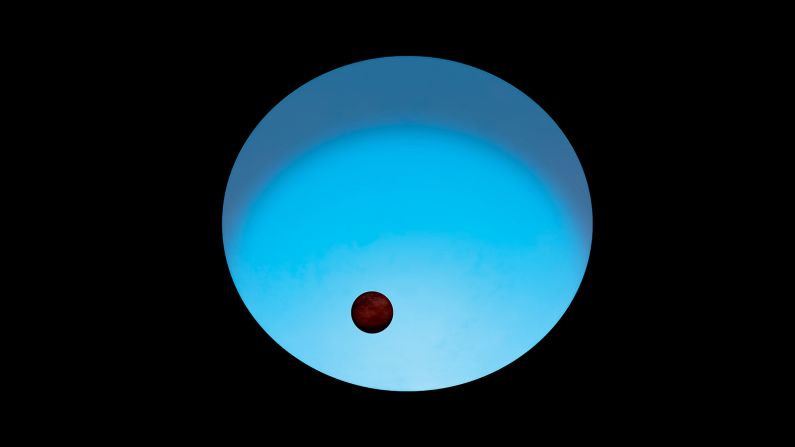

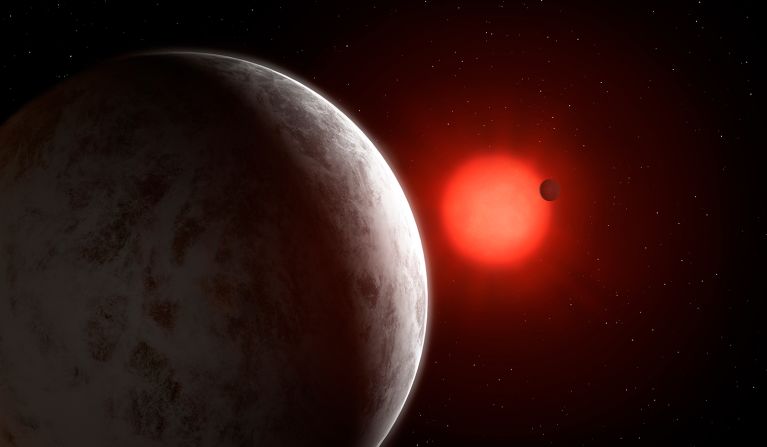

OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is as close to its star as we are to the sun, but it's an ice world

The planet's star is 10,000 times fainter than our sun

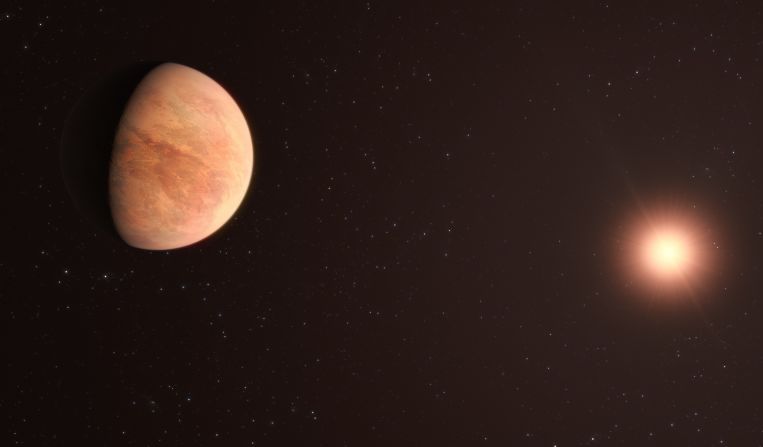

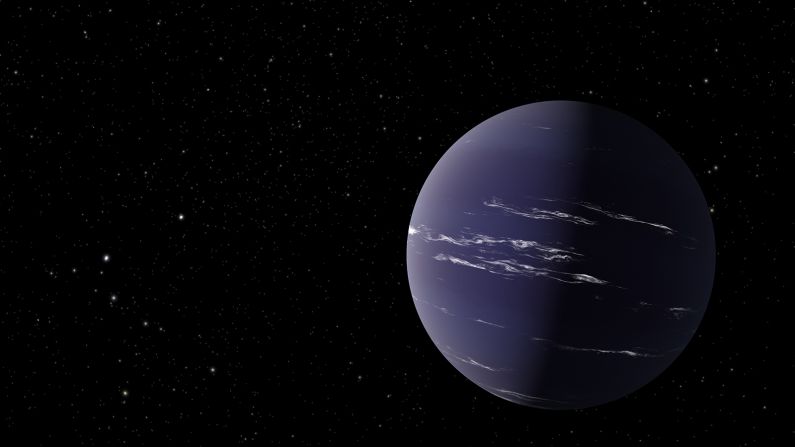

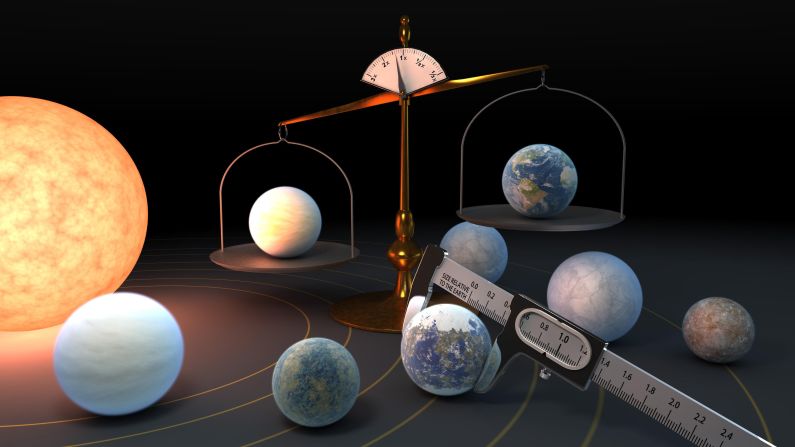

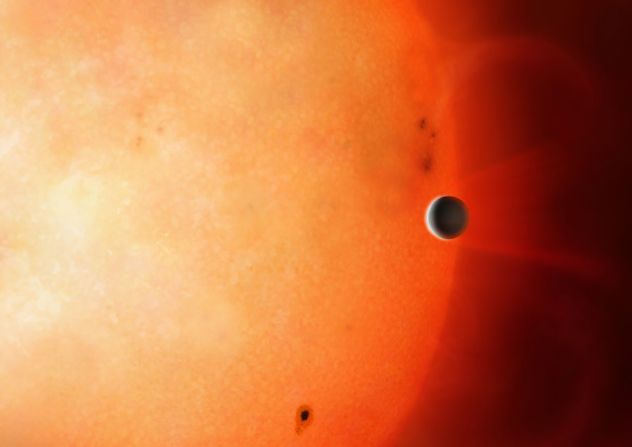

This newly discovered exoplanet may be Earth’s twin in terms of mass and the distance from its host star, but you wouldn’t want to visit. Researchers say it’s an “iceball.”

In “Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back,” Princess Leia, Luke Skywalker and the rest of the rebels toughed it out on Hoth, an icy world, until they were discovered by Imperial forces. But OGLE-2016-BLG-1195Lb is even less hospitable.

“While it is covered in ice, at around minus-400 degrees Farenheit, it is actually much, much colder than Hoth,” said Yossi Shvartzvald, postdoctoral fellow at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and lead author of a study detailing the planet in Astrophysical Journal Letters. “It’s hard to imagine any life surviving in such an environment, not humans or tauntauns anyway.”

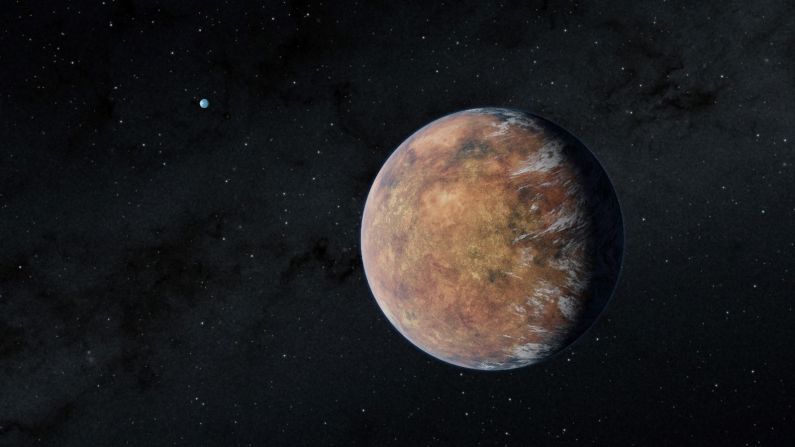

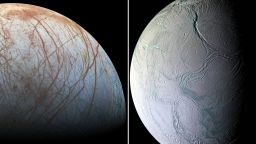

At least Hoth was livable, like the North or South poles on Earth, added co-author Jennifer Yee of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics. The newly found exoplanet is colder than Pluto, which is colder than liquid nitrogen. Because of that, Yee imagines that the planet might resemble Pluto.

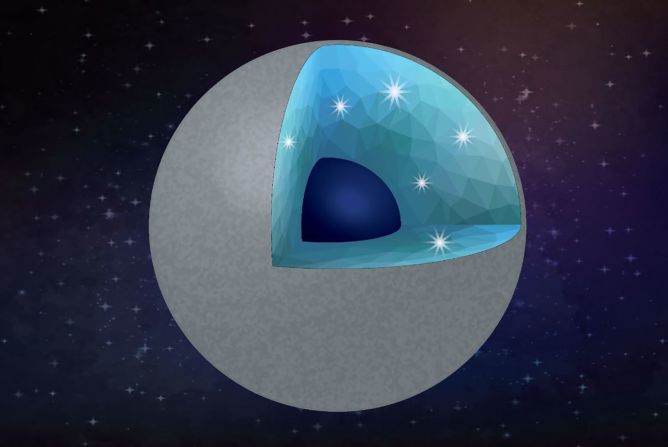

“The planet might look something like snow at sunset but even darker,” Shvartzvald said. “The ice is not just scattered on the surface; it goes hundreds of miles deep.”

That icy surface is incredibly reflective, about five times as shiny as Earth’s moon, he said. But it can’t really reflect much light due to the nature of the star it orbits.

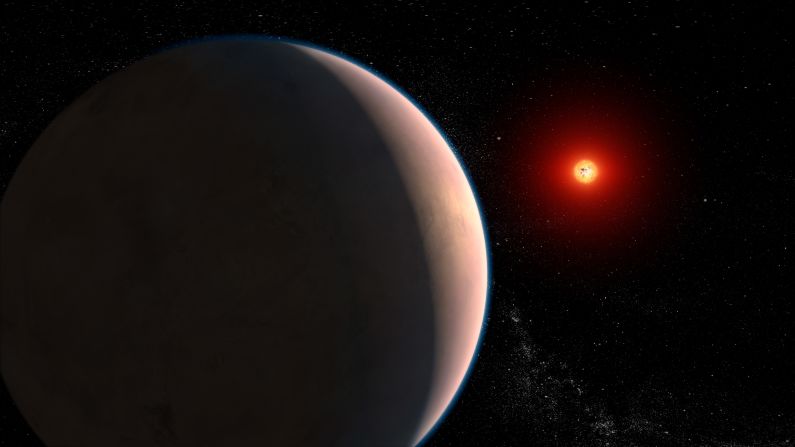

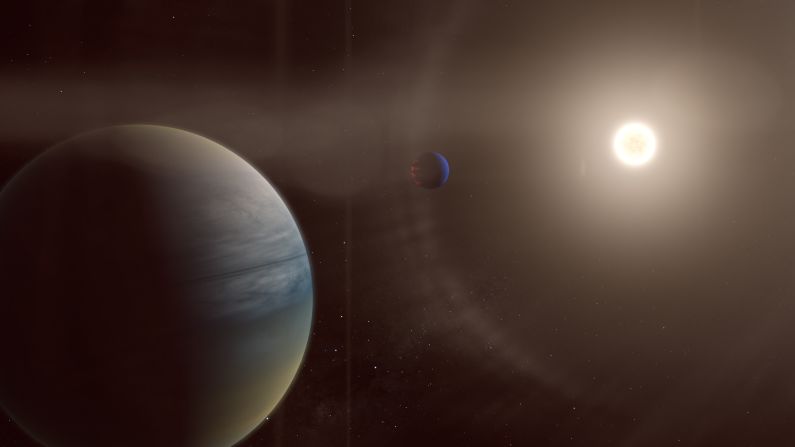

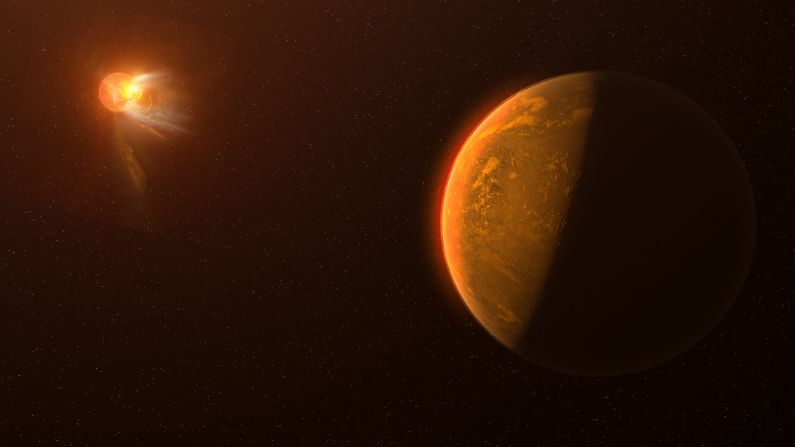

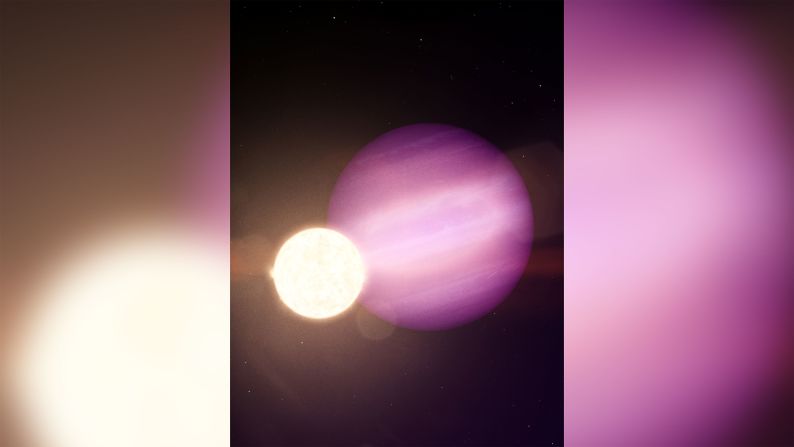

Thirteen thousand light-years away from us, the planet orbits a star 10,000 times fainter than our sun. The researchers believe that the star is either a brown dwarf or an ultracool dwarf, which is at the low end of the spectrum for stars. But they don’t have a way of knowing that right now.

Even though the planet is well out of our reach, the researchers were able to confirm the planet and its mass and distance to the star with data gathered using the ground-based Korea Microlensing Telescope Network and the Spitzer Space Telescope.

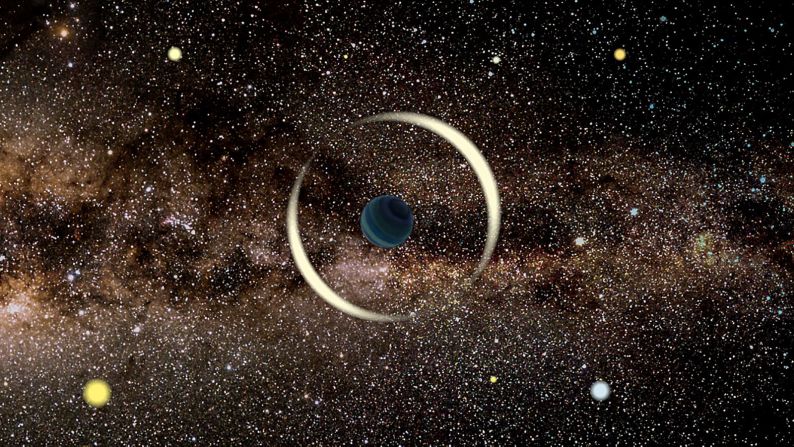

They used a technique called microlensing, which has enabled astronomers to find the most distant exoplanets orbiting stars thousands of light-years away. To date, this is the lowest-mass planet found through microlensing.

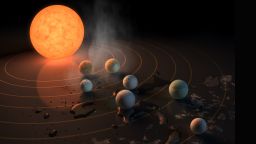

“This discovery provides more evidence that planets are not only very common but also very diverse,” Shvartzvald said. “They are able to form in strange environments very different from what we’re accustomed to on Earth.”

It leaves Shvartzvald wanting to answer questions about how common these systems are. Currently, there are no ground-based telescopes that can use microlensing to find exoplanets smaller than this one.

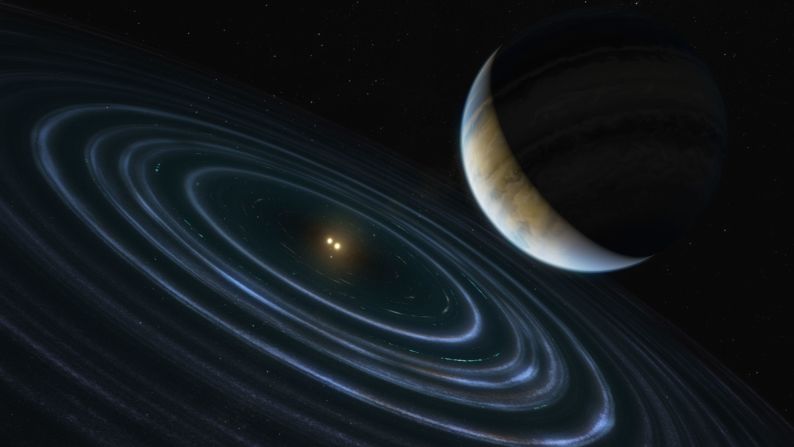

That’s why researchers are looking forward to the launch of WFIRST, NASA’s Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope, in the 2020s. Shvartzvald even anticipates that WFIRST will allow for the discovery of exomoons, among other smaller objects, and a more complete census of exoplanets and how they formed.

“WFIRST will allow us to find and characterize thousands of planets,” Yee said. “I’m excited to see what that full distribution of planets looks like, because it will give us a more complete understanding of whether planetary systems have architectures similar to our solar system or very different.”