Story highlights

Only three national monuments are dedicated to women, and no national memorials

Movements across the US are trying to change that

Lady Liberty is one of the United States’ most famous symbols. But this female personification of freedom and hope stands virtually alone in a sea of male-centered monuments that dot the American landscape.

The relative lack of women represented in landmarks, public sculptures and street names has spurred a wave of efforts – from congressional commissions to individual initiatives – trying to bring about change.

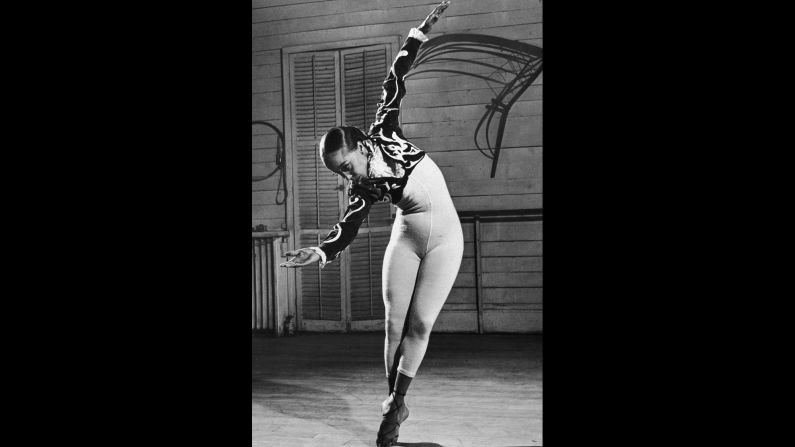

Of the 5,575 outdoor sculpture portraits of historical figures in the United States, 559 portray women, a mere 10% of all statues, according to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s online inventories catalog.

The National Park Service lists 152 monuments in the United States, which range from buildings to volcanoes and canyons. Only three (less than 2%) are dedicated to historic female figures: Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historic Park in Maryland, the Belmont-Paul Women’s Equality National Monument in the District of Columbia, and the Rose Atoll in the US territory of American Samoa, named for a female explorer. All three have been established in the past decade.

None of the 30 national memorials managed under the park service specifically honor women, though there’s one named after a shrub, the four-wing saltbush (Chamizal).

“It’s abysmal and it is going to change, because people will gradually be encouraged to think how they want to honor women in their own community,” says Pam Elam, president of the Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony Statue Fund.

This sentiment comes as millions observe International Women’s Day on Wednesday.

Elam’s organization advocates placing a statue of the two women’s rights pioneers in New York City’s iconic Central Park, which in its 164 years has erected 23 statues honoring men and none honoring real women (Mother Goose and Alice in Wonderland, alas, never existed).

Of the almost 200 full-sized figurative statues in the entire New York City area, NYC Parks says only four represent real women. In 2015, Commissioner Mitchell Silver gave both his approval and blessing for Elam’s project.

A spotlight on women achievements

Elam is part of a larger movement aiming for change across the country.

In Washington, the American Museum of Women’s History Congressional Commission has presented a study conducted over 18 months.

“After studying all the very rich history that women have been part of, there is just no entity out there right now that is doing a complete job,” says Jane Abraham, the commission chair. “Women have played major roles in the mosaic of our country and those should be taught and illuminated.”

Perhaps the most successful campaign thus far belongs to Lynette Long of Miami Beach, Florida, whose nine-year effort is now bearing fruit in the form of an Amelia Earhart sculpture in the Capitol’s National Statuary Hall.

Long wrote her first op-ed on underrepresentation of women in the early 1990s, when she went to the post office and there were hardly any stamps of women. She said it was the “unbelievable sexism” of the 2008 election campaign that drove her to establish Equal Visibility Everywhere, a group dedicated to achieving gender parity in the symbols and icons of the United States.

An educator, psychologist and author of mathematics books, Long has always been following the numbers. “Statuary Hall gets three to five million visitors a year, it’s on TV all the time, it gets more visibility than any museum in Washington and it’s a symbol of our nation and history,” she says.

There are currently 100 statues in Statuary Hall, two for each state, and only nine depict women. Earhart, the famous 1930s aviator, is going to be the 10th and is under construction, representing Kansas, Long said.

Mapping history's 'invisible' women

Meanwhile in Maine, Colby College is hosting an initiative of the Spark Movement called Women on the Map, a project on the Google app Field Trip dedicated to locating and presenting historically significant achievements of women.

Co-director Dana Edell tells CNN the project has doubled its stories to 200, thanks to an outpouring of response during the latest election campaign and the prospects of a female president. They are now fundraising to create an improved standalone app.

Joining the existing initiatives is Put Her On The Map, a new project of ad agency BBDO, which launched in February and aims to encourage cities and corporations to name streets, statues and buildings after influential female figures.

The city of Los Angeles, which claims to have recently eliminated all-male boards and commissions for the first time, has expressed interest in the initiative. “Women’s contributions to the history and progress of Los Angeles are beyond measure. And when their names are immortalized on our infrastructure and landmarks, that simple but powerful act means that countless women and girls will be inspired,” said Mayor Eric Garcetti.

The obstacles ahead

“There has been a concerted effort in the past eight to ten years to tell a broader and inclusive American story,” says Jeffrey Olson, a spokesman for the National Park Service.

The drivers often are public engagement and studies that are done periodically to point out parts of the American narrative that are underrepresented, Olson says. But he adds that he was never asked to present a gender-based comparison.

Long believes it all begins with awareness.

“When we started our organization, people didn’t notice that when the new 56 quarters were out, only one state – Alabama – had a woman on the back,” she says. Long also became vocal when she noticed the scarcity of women in the early Google Doodles. “When we reached out to them they weren’t aware of it, they didn’t even think about it. I don’t think they were intentionally sexist. You make them aware and it changes.”

Then there’s also funding and location hurdles.

“We encourage statues or other monuments outside of Manhattan, which is considered prime location. We just don’t have enough space,” says NYC Parks Commissioner Silver. “In order for us to consider suggestions, the entity has to raise the funds and make the commission. We are open for any appeal but park land is limited.”

For their Central Park project, Elam and her group must raise $1.5 million. She claims they had to overcome obstacles such as providing evidence of Stanton and Anthony’s historical presence in the park. “I doubt that any of the other statues of men had to go through those levels of specificity,” Elam says.

But after receiving a recent $500,000 challenge grant from New York Life, they are moving toward an April release of a request for proposals for sculptors interested in entering the statue design competition.

They hope their vision will be completed by August 2020, the centennial of women suffrage in the United States.

In Washington, the envisioned museum dedicated fully to the American women’s history also faces budgetary issues, says commission chair Abraham.

Although officially done with their commission duties, Abraham and her seven colleagues are working with the Smithsonian Institution on how to launch the first step of the plan toward a 2026 grand opening.

The Smithsonian will start by pulling together collections, curators and exhibits focusing on the missing areas while the often-slow political and legislative process will shift in motion, Abraham says. “The eight of us are committed to work to make sure this actually leads to a museum, working with them on ideas on how to tap private sector interests to speed the process,” she adds.

As for Long, she is not stopping at Earhart. Writer and activist Marjory Stoneman Douglas will be her lucky number 11 in the national hall – if the Florida Legislature acts.

“It’s always a battle,” Long says, recalling her attempt to get “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” author Harriet Beecher Stowe to represent Ohio, but losing the spot to inventor Thomas Edison. “People don’t want to give the spots up and even if they do there’s a lot of competition.”

She’s also reaching out to the Macy’s Thanksgiving parade, to convince them to add more empowering female figures to the balloon march.

“I grew up watching that parade every Thanksgiving and never realizing that my whole life there were so few female cartoon figures in it,” she remembered. “It’s so subliminal that it never dawned on me, and it never dawns on anyone unless you point it out.”