Story highlights

Soccer players who frequently head the ball are more likely to have concussion symptoms, a study says

Players suffering several accidental head hits were six times more likely to have concussion symptoms

Whether in practice games or competition, soccer players who frequently head the ball are three times more likely to have concussion symptoms than players who don’t rack up high numbers of headers, according to a study published Wednesday in the journal Neurology.

When a bump, blow or jolt to the head or a hit to the body causes the head and brain to move rapidly back and forth, this can lead to concussion, a type of traumatic brain injury. The brain bouncing or twisting in the skull creates chemical changes in the brain and sometimes damages cells, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Dr. Michael L. Lipton, senior author of the study and a professor of radiology and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine, noted one important reason why he conducted the research: “There’s like over a quarter of a billion people in the world who play soccer, and most of those people are the kind of people we study,” he said of adults in recreational leagues.

“It’s a huge number of people. So if there is an effect on the brain – and as the data comes in, it’s increasingly looking like there is – that’s potentially a big public health issue.”

Finding answers

For this study, adult amateur players who played soccer at least six months of the year in leagues or clubs completed an online questionnaire. Their answers sketched individual portraits of how frequently they played soccer during the previous two weeks, the number of times they headed the ball and how many times they accidentally got hit in the head by the ball. A total of 222 players, 79% men, completed the questionnaire. Some of these same participants completed additional rounds of questionnaires.

Lipton and his colleagues divided participants into four groups based on how often they headed the ball. The top group, on average, headed the ball 125 times in two weeks, while the bottom group averaged just four headers in that same time period.

Participants also described any central nervous system symptoms after head impacts: Twenty percent had moderate to severe symptoms. As defined in the study, moderate symptoms included feeling some pain and dizziness. Severe symptoms included feeling dazed, stopping play or needing medical attention. “Very severe” referred to a player being knocked out; seven people reported losing consciousness.

Gathering and analyzing the data, the researchers discovered that soccer players in the group that headed the ball the most were three times more likely to have symptoms than those who headed the ball the least.

Players suffering two or more unintentional impacts were six times more likely to have symptoms than those with none, while players with just one accidental hits were three times more likely.

“Unintentional impacts – essentially this is our code word for collisions or falls,” Lipton said, explaining that even with fewer numbers, unintentional hits were very strongly associated with symptoms.

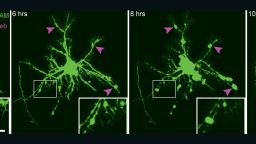

In a previous study, Lipton and his colleagues discovered that 30% of soccer players had more than 1,000 headings per year and had a higher risk of microstructural white matter changes in the brain, which is typical of traumatic brain injury, and worse cognitive performance. MRI exams are part of the longer study that provided data for this current paper and will be reported in the future, explained Lipton.

“The good news about concussive injuries is that the vast majority of people recover,” he said. “What’s not known is, when you have repeated injuries of this type, what is the long-term cumulative effect?”

Supported by the National Institutes of Health, the study results cannot be generalized to teens, children or professional soccer players, Lipton said, also noting that self-reported data, which were used in the study, can be inaccurate.

Different views

Anthony P. Kontos, associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh and research director at the UPMC Sports Medicine Concussion Program, agreed that self-reported data are a problem.

“As a lifetime competitive soccer player, I have no idea how many headers I perform in practices or games – even if you asked me the same day, let alone two weeks later, as in the current study,” said Kontos, who was not involved in the current research. Another weakness of the study, he said, was the fact that the researchers failed to control for the type of header. Not all headers are the same.

“The sample did not exclude players with a history of concussion, so we have no idea if the reported effects simply reflect a history of concussion,” he explained, adding that the low response rate calls into question how representative the sample participants are.

However, one strength of the study is the fact that the researchers controlled for the effects of age, sex and competitive level. Another strong point is the primary finding itself: that participants in the highest group were most at risk for symptoms since this group headed the ball excessively, over four times more than the next group. This is “intuitive,” Kontos said.

“Concussions in soccer mostly occur from player-to-player and player-to-ground contact. Heading is involved in only 15% to 25% of concussions in soccer, and most of those are a result of poorly executed headers where two players hit heads,” Kontos said, based on his knowledge of recent research on the topic.

This suggests “we need to do more to teach kids how to properly and safely head the ball.”

No more denial

Meanwhile, much of the latest research focuses on better diagnosis of traumatic brain injury, according to Dr. Sam Gandy, director of the NFL Neurological Center at Mount Sinai Hospital.

“There’s more intense search for objective markers of brain damage, more effort to get answers quickly, even some tests that can be used on the sidelines to assess concussion in real-time during play,” said Gandy, who was not involved in the current study. “I think one of the major advances is a change in attitude.”

For a long time, there’s been denial that brain injury might have longer-term consequences to players. “Now, that’s no longer happening,” Gandy said.

There are injuries to the brain associated with sports – including shaking and sub-concussive injuries – “that don’t necessarily rise to the level of what’s classically used to diagnose a full-blown concussion on the sidelines, where someone is stunned and they don’t know who they are or where they are,” Gandy said. “It’s clear there are injuries far short of that that can be associated with changes in physiology and appearance in the bloodstream of proteins derived from the brain.”

Although no one is quite sure how bad each sport could be for each gender and age group, he said, coaches, team owners and players are more aware of brain injuries. Overall “resistance to the notion that this may not be a good idea has started to crack a bit,” he said.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

One example: A December 2015 ruling by US Soccer, the game’s American governing body, prohibited heading in games or practice for any players age 10 and younger and advised only limited heading for players between the ages of 11 and 13.

“We took the position that once we’ve told people what we expect them to do, we’d like to help them with how to do it,” said Ian Barker, director of coaching education at the National Soccer Coaches Association of America.

In September, the association released an interactive online course that provides “coaches and parents with a practical tool” for introducing players to heading, Barker said. Working with Tom Kaminski, a professor at the University of Delaware, the association identified ways concussive impact of a soccer ball hitting the head can be reduced, Barker said. Kaminski, who is director of athletic training education at his university, did not participate in Lipton’s study.

Essentially, if a child has good technique plus “improved core strength and neck musculature,” concussive impact is lessened, Barker said.

“Kids bump heads with other kids; kids bump heads with the ground; kids bump heads with goalposts and other inanimate objects,” he said. “The University of Delaware and ourselves are not finding high instances of concussive injury directly as a result of trying to head the ball properly.”

More commonly, he said, it’s the accidental bumps and falls that lead to concussions.

Beyond soccer

Meanwhile, Lipton stands by his work.

“Professional guidelines all discuss concussion as a consequence of soccer but indicate that heading is an ‘uncommon’ cause of concussion,” he said. Yet heading accounted for an entire segment of “symptomatic events,” even if some admittedly may not be considered concussive.

“What we’re showing here is there clearly is an acute effect,” Lipton said. “That at least compels us to really think about what the long-term effects are and to study that.”

Soccer players “are very unique in that they will predictably have repeated impacts to the head which we can characterize and quantify,” he said, which makes them “an incredibly robust model system for looking at repetitive head injury.”

“The biggest problem with brain injury research, which I’ve done a lot of, is that when someone comes to the emergency room with a head injury or when a soldier has a blast injury, we don’t have any baseline of what they were like beforehand,” Lipton said. Doctors also don’t have access to “a way to characterize the magnitude of the exposure – meaning how much injury they had.”

A secondary aim of his study, he said, is “trying to characterize how the brain responds to repetitive injury, which have huge implications that go beyond soccer.”