Story highlights

Premature mortality rose for white, American Indian, Alaskan Native populations between 1999 and 2014

Two key reasons were accidental deaths, largely attributable to drug overdose, and suicide

Black, Asian and Latino early deaths have decreased

Premature death is on the rise for Native and white Americans in the United States, with drug overdose and suicide contributing heavily to the increase, according to a new study.

“What surprised me the most was the size of the increase,” said Meredith Shiels, an investigator with the National Cancer Institute’s Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics. Shiels was lead author of the study, published Wednesday in the journal The Lancet.

From 1999 to 2014, mortality surged as high as 2% to 5% per year among white, Native American and Alaskan Native people ages 25 to 30.

“The last time we saw increases like this was during the AIDS epidemic in the ’80s and ‘90s,” Shiels said.

In contrast, other minority groups – people of black, Asian and Hispanic origin – have seen fewer deaths among 25- to 64-year-olds than in years past, partly due to gains in the treatment and detection of cancer, HIV and heart disease, according to the study.

African-Americans saw some of the steepest declines in premature deaths, up to 3.9% per year for certain ages.

Accidental deaths, including drug overdoses, increased in all 50 states for women and in 48 states for men. West Virginia had the highest rate of early death from all causes, while the District of Columbia had the lowest.

For whites, “the numbers are being dragged down … by prescription and opioid overdoses,” said Dave Thomas, a program official in the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Division of Epidemiology Services and Prevention Research. Thomas was a coauthor on the study.

Thomas described opioid abuse as “an usual epidemic” in that it affects predominantly white people and started in rural areas.

“I don’t think we have a complete understanding of why it’s happening that way,” he said.

Thomas said a number of initiatives have aimed to tackle drug overdoses, such as addressing opioid prescription guidelines and distributing naloxone, which reverses overdoses.

“It’s a crisis,” he said. “There’s not just one simple answer.”

Previous research has linked substance use to suicide, another key driver of the mortality increase among young white and Native Americans. However, the study does not make clear whether and how these trends might be linked. Suicide was the only major cause of death to climb consistently among Asian-Americans, according to the study.

Despite the uptick in premature death rates among white Americans, they still live longer on average than black Americans. But this life expectancy gap has been closing, from 5.9 years in 1999 to 3.6 years in 2013, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In 2015, the life expectancy for the average American dropped for the first time since 1993, though only by 0.1 year, according to a report last month by the CDC. According to the report, the average woman lives to be 81.2 and the average man 76.3.

“It’s important to have the full context,” Shiels said, adding that the rise in white and Native American deaths is only one part of a picture that includes “great progress in other racial groups.”

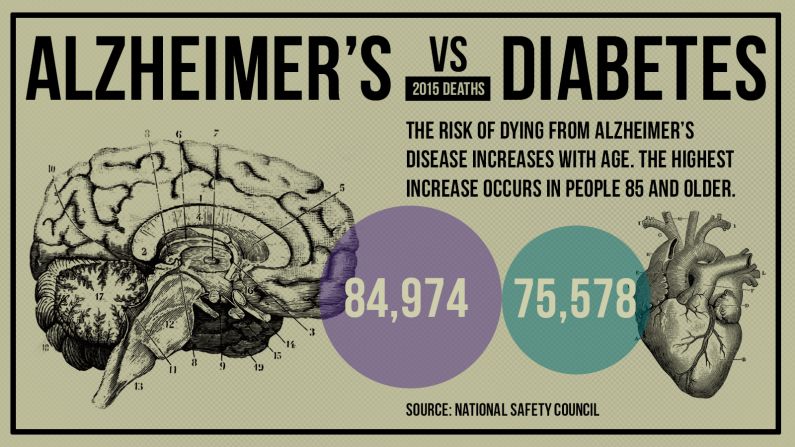

Despite the increase in diabetes-related deaths for younger Native Americans in the Lancet study, a 2014 study in the American Journal of Public Health showed falling trends in diabetes-related deaths in the 2000s. A recent CDC Vital Signs report showed that kidney failure from diabetes plummeted 54% in Native Americans between 1996 and 2013.

“Diabetes itself has plateaued in our population,” said Dr. Ann Bullock, one of the authors of the 2014 study and director of the Division of Diabetes Treatment and Prevention for the Indian Health Service.

Bullock, a member of the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, cautioned that the Lancet study, an analysis of death certificates, may provide imperfect data.

“Most people don’t die of diabetes,” she said. “Whether someone gets that put on their death certificate” can depend on other factors, such as physician bias.

Because many doctors associate Native Americans with diabetes, Bullock said, some may be more prone to add it to their death certificates.

The data can also depend on how patients’ races and ethnicities are recorded. Because Native Americans are commonly mixed-race, Bullock said, many do not self-identify, and others who may not “look” Native American may be misclassified by hospital intake staff.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

When it comes to high rates of chronic diseases, substance use and other causes of death in the Native American community, Bullock said “a lot of these have behavioral health roots to them” that require a complex lesson in Native American history.

She said these numbers and statistics reflect the loss of native land and culture, as well as a dearth of resources and employment in many Native American communities.

“It’s a far more complicated picture than ‘Just snap out of it and you’ll be fine.’ “