Editor’s Note: John D. Sutter is a columnist for CNN Opinion who focuses on climate change and social justice. Follow him on Snapchat, Facebook and email. This story is part CNN’s “Vanishing” series. Learn more about the sixth extinction and get involved.

The “blue jeans” frog is practically screaming to be noticed. Its head is blood red, and its legs are denim blue. It looks like it’s wearing jeggings. But this little critter, also known as the strawberry poison dart frog, is only about the size of a fingernail. It spends most of its time either high up in the trees in this Central American rainforest or rooting around in the gooey “leaf litter” of the forest floor.

As such, it’s practically invisible.

Unless you open your ears.

Chit-chit-chit-chit-chit.

“It sounds like an insect. It buzzes.”

That’s Bryan Pijanowski, a “soundscape ecologist” from Purdue University and one of the few people paying attention to the fact that nature – especially the amphibian part – is growing exceptionally quiet these days. Pijanowski and collaborators from around the world have been strapping audio recorders to trees here at La Selva Biological Station in Costa Rica. The microphones look like funny little robots – boxes with windscreen ears on each side.

The equipment has a critical mission.

It’s listening for the sound of extinction.

Have you heard it already? I ask Pijanowski.

“I think so,” he tells me. His muted, baritone voice sounds like a public radio host sharing secrets with you in a library. “There is evidence all around the world.”

‘Rapid extinctions’

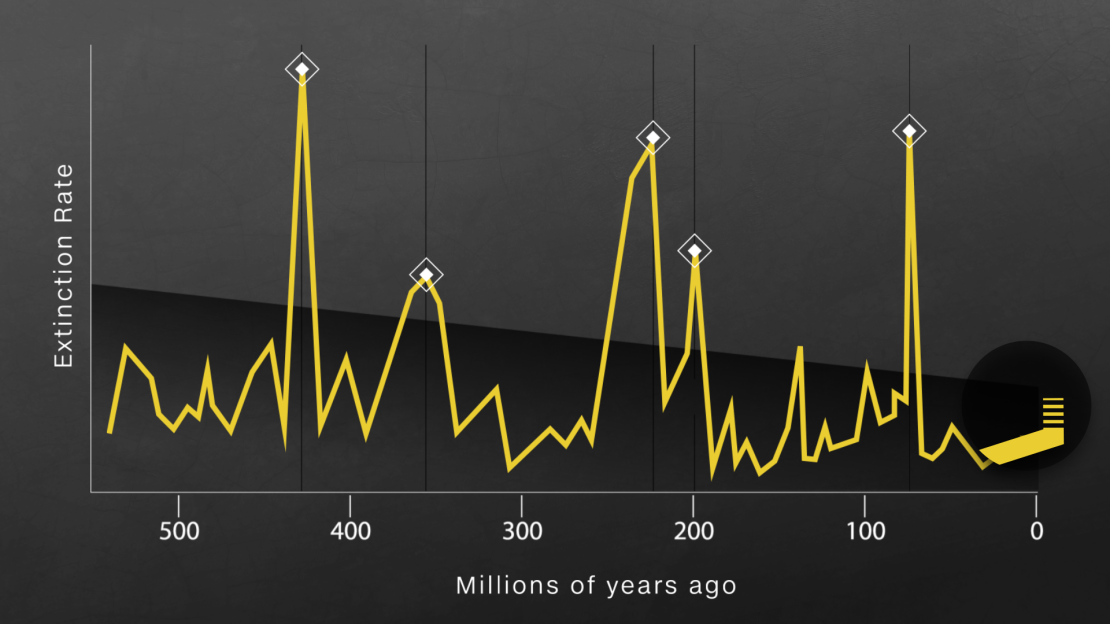

Scientists fear Earth is on the verge of the sixth era of extinction.

There have been five mass extinctions in the planet’s history.

If we usher in the sixth, three-quarters of all species could disappear in a couple of centuries, says Anthony Barnosky, executive director of the Jasper Ridge Biological Preserve at Stanford and author of “Dodging Extinction: Power, Food, Money and the Future of Life on Earth.”

“The best way to envision the sixth mass extinction,” he told me, “is to look outside and then just imagine that three out of every four of the species that were common out there are gone.”

If you study amphibians, it can seem like that dystopian future already is here.

About 10% of birds and a third of mammals are at high extinction risk.

Not good.

But more than 40% of amphibians are in similar straits – making them worse off than any other vertebrate group, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

Amphibians are vanishing without warning, and often without explanation.

“In the past 30 years or so, we’ve seen really dramatic, really rapid extinctions for frog populations all over the world,” says Steven Whitfield, a conservation ecologist at Zoo Miami who joined Pijanowski and me on the visit to Costa Rica this summer. “Many of these extinctions are due to habitat loss. But other extinctions have occurred in pristine rainforests like this – places that look healthy but the frogs are telling us there’s something clearly wrong.”

‘Unable to see it’

Whitfield spent years studying frogs at this research station in this particular forest.

I ask him to show me how it’s done.

It doesn’t take long to realize it’s not easy work. When Whitfield conducts a study, he often ropes off a small plot of land and then spends hours searching for every single frog he can find.

The search begins with his ears.

“I’ll hear [a frog] call and spend half an hour or more looking into a small patch of vegetation, knowing that it’s right there and that I need to find it but unable to see it,” he tells me.

Whitfield is an expert at pulling frog sounds out of the EDM freak-out that is the rainforest. If you’ve been, then you know these places, in healthy conditions, are LOUD. I actually had a hard time falling asleep some nights in Costa Rica because it sounded (awesomely) like the forest was yelling at me; and I woke up early to screams of howler monkeys. (Fun aside: Researchers warn newcomers to always wear shoes – because, vipers – and to watch the trees, since the “bullet ant,” which delivers the world’s most painful bite, like a bullet, is all around.)

Whitfield’s amphibian-listening powers are impressive, but even he has trouble finding frogs by sight. He takes me and a group of researchers from the Center for Global Soundscapes deep into the forest just after dusk one evening, when some frogs tend to be the most active. Our headlamps provide a washed-out sort of tunnel vision of the diversity hiding all around us.

Whitfield can hear and identify frogs at great distance. There’s the “chit-chit-chit” of the blue jeans frog (the one with jeggings), the panicked meowing of a creature aptly nicknamed the “kitten frog.” He hears the slot-machine rattle of the “glass frog,” which has a translucent belly, allowing you to see organs through its skin. Smoky jungle frogs scream like human babies when they’re threatened, and the tink frog seems to be named for its metallic call, which sounds like that ear-piercing noise a smoke detector makes when it wants you to change its battery.

This place is way beyond “ribbit.” The sounds are staggering.

But finding these frogs by sight?

That’s more difficult.

In a couple of hours, we saw only a handful of frogs.

Spiders almost seem easier to come by.

“Those bite,” Whitfield says, pointing to one. “Don’t touch that.”

‘Something is happening’

I’m grateful for the research Whitfield and other field ecologists have contributed when it comes to frogs. Their diligent, painstaking, searching-through-the-leaves work is how we know important (and fun) frog facts, like that the female blue jeans frog is an amphibian supermom.

Her tadpoles hatch on the forest floor, he says, but that’s a precarious place for them, so she carries them, on her back, high up into the forest canopy, sometimes 10 to 15 meters off the ground – about 33 to 50 feet. She drops the tadpoles off in little puddles of water up there in the forest canopy and makes a mental note of their location. She does this again and again, leaving her young all over the forest canopy. She remembers where all these tadpoles are (!!) and spends her days climbing the trees to deliver food.

“That’s pretty complicated behavior for a tiny little frog,” Whitfield says.

His research also has helped show that frogs at La Selva are in decline.

“We have really good long-term data on what’s been happening with frog populations over four decades,” he tells me. “In the forest here now, there’s only about 25% as many frogs as there were sustained throughout the 1970s. And for us, that’s a concern because it says that something is happening to this rainforest but we don’t fully understand what that is.”

That’s worth stating again.

Locally, only a quarter of the frogs from the 1970s remain.

Meanwhile, the human population jumped from less than 4 billion to 7.4 billion today.

Whitfield’s search-the-forest work is critical.

But even he would say it could use a technological assist.

That’s where Pijanowski and his tree-hugging microphones come in.

He’s listening for changes Whitfield might not be able to see.

‘Your ears ring’

Bryan Pijanowski is an ecologist by training. Before that, he was a “quiet alterboy-ish kind of kid” in the Midwest who also was sort of an audiophile – and an amateur musician. He played guitar in a high school band called Destruction. “Everybody wanted you to play ‘Freebird,’” he said, “so that’s what I played – over and over again.”

In school, he set out to become a medical doctor but changed his mind after hearing the “dawn chorus” of a swamp in Michigan. He became obsessed with nature and its music.

So he studied birds and ecology, and eventually turned to “soundscapes,” the emerging field of using sound to understand the shifts in the health and function of ecosystems.

The work makes him so sound-focused he now has to wear earplugs to sleep.

He can’t stop listening.

“There are times when [the rainforest] is almost too loud,” he tells me.

“It’s like being too close to the speakers at a concert. Your ears ring.”

More from CNN's 'Vanishing' series:

La Selva is now one of his study sites. He’s working to develop others around the world, including underwater to listen for changes to coral reefs. His microphones have taken him to the tip of South America and the deserts of Mongolia. But this site is special both because the rainforest is nearly untouched – and because there’s so much data. Pijanowski got his hands on recordings that date back to 2008 and started making his own recordings here in 2010. At the peak of his research, he’d installed 34 microphone sensors.

Now he has 255,000 recordings here, totaling about 6.8 years of tape.

He’s still analyzing the data with the help of computer algorithms.

What he’s heard – or rather, what he doesn’t hear – definitely freaks him out.

‘Acoustic fossils’

One evening, insects and frogs chattering outside, Pijanowski sits me down in an open-window classroom at the research station and shows me some of his sound files.

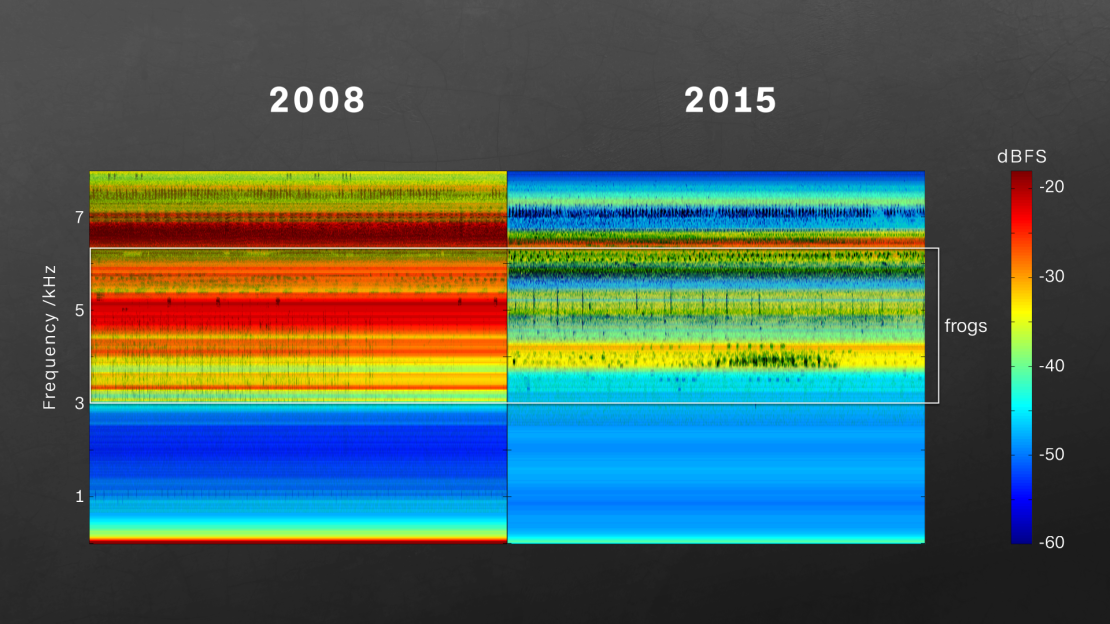

He visualizes the audio in charts called spectrograms.

These charts illuminate trends that a walk through the forest can’t.

Take a look at this La Selva recording from 2008.

And then another from 2015, recorded under similar conditions.

Hear the difference?

Those are just two moments.

Pijanowski’s team can compress a year’s worth of sound into one chart.

Take a look at what happens when you look at those years side by side. The red parts of the charts indicate more audible activity. The main frog frequencies grow much bluer, and quieter.

It’s too soon to draw scientific conclusions from this, Pijanowski tells me.

But he’s frightened.

“I’m worried that these would potentially become acoustic fossils,” he says.

“In other words, the animals that are in these files are no longer alive. And the only record that we have of some of their presence is in an audio recording.

“That is somewhat disturbing to me, as a scientist and also as a citizen of this planet.”

A collaborator of Pijanowski’s, Michael Towsey, tells me he has a file of an Australian frog that’s thought to be extinct – a recording that already is an acoustic fossil.

You can listen to that frog’s call here on the Internet.

But you can no longer hear it in nature.

‘Most beautiful sound in the world’

Why does this matter?

There’s the self-interested argument.

Here’s Steven Whitfield’s take on that.

“We are all dependent on the planet for clean water, for oxygen. And ecosystems not only provide food to people but rainforests like this are an important source of medicines. Some of the frogs that live in the rainforest here have chemicals in their skin that have been found to be important medicines. They can be painkillers or heart medicines. So these are things that can be really useful for medicine. And we’d like to not lose those. If we do lose those, it hurts us all.”

There’s the ecosystem collapse argument.

Bryan Pijanowski: “Some of the theoretical work that we’re doing and ecology suggests that we could have ecosystem collapse. And that’s not good … You don’t wanna start removing organisms and expect the ecosystem to survive and function in a healthy way. It could very well mean that some of the things that we are much more emotionally attached to are lost.”

That should be enough to sway a pragmatist.

Still, I think there’s a more human reason you should care about the disappearance of amphibians.

Chances are you never or rarely see frogs in your day-to-day life. But when you learn about them – those with translucent bellies, supermom instincts, blue-jean legs and poisonous skin, all of which are calling to be noticed by each other if not by us – then it’s hard to ignore their plight.

There are multiple causes of the amphibian apocalypse, but all the trouble points back to us. We’ve helped carry a killer fungus, called chytrid, around the globe, with disastrous consequences. Climate change has been implicated in frog die-offs. Pollution is a big problem since frogs live part-time in water and basically breathe through their skin.

They are the front lines – the most vulnerable of species.

Yet few of us seem truly outraged by their disappearance.

Maybe that will change if we start listening more closely.

After all, frog choruses are some of the most fascinating songs in nature.

One recording from the island of Borneo – called “dusk by the frog pond” – was voted by the always-wise Internet as “the most beautiful sound in the world.”

It’s not too late to stop the sixth extinction from taking permanent hold of us, according to Barnosky, the Stanford researcher. We have at most 20 years to change our ways.

There’s hope. But we must ditch fossil fuels, mitigating climate change. We have to stop the spread of invasive species and disease. And, in the view of one prominent biologist, we must set aside half the planet for the benefit of biodiversity and nature.

Otherwise, we risk silencing the frogs.

And perhaps the rest of nature, too.