Story highlights

It's a key indicator of climate change and can mean changes to weather

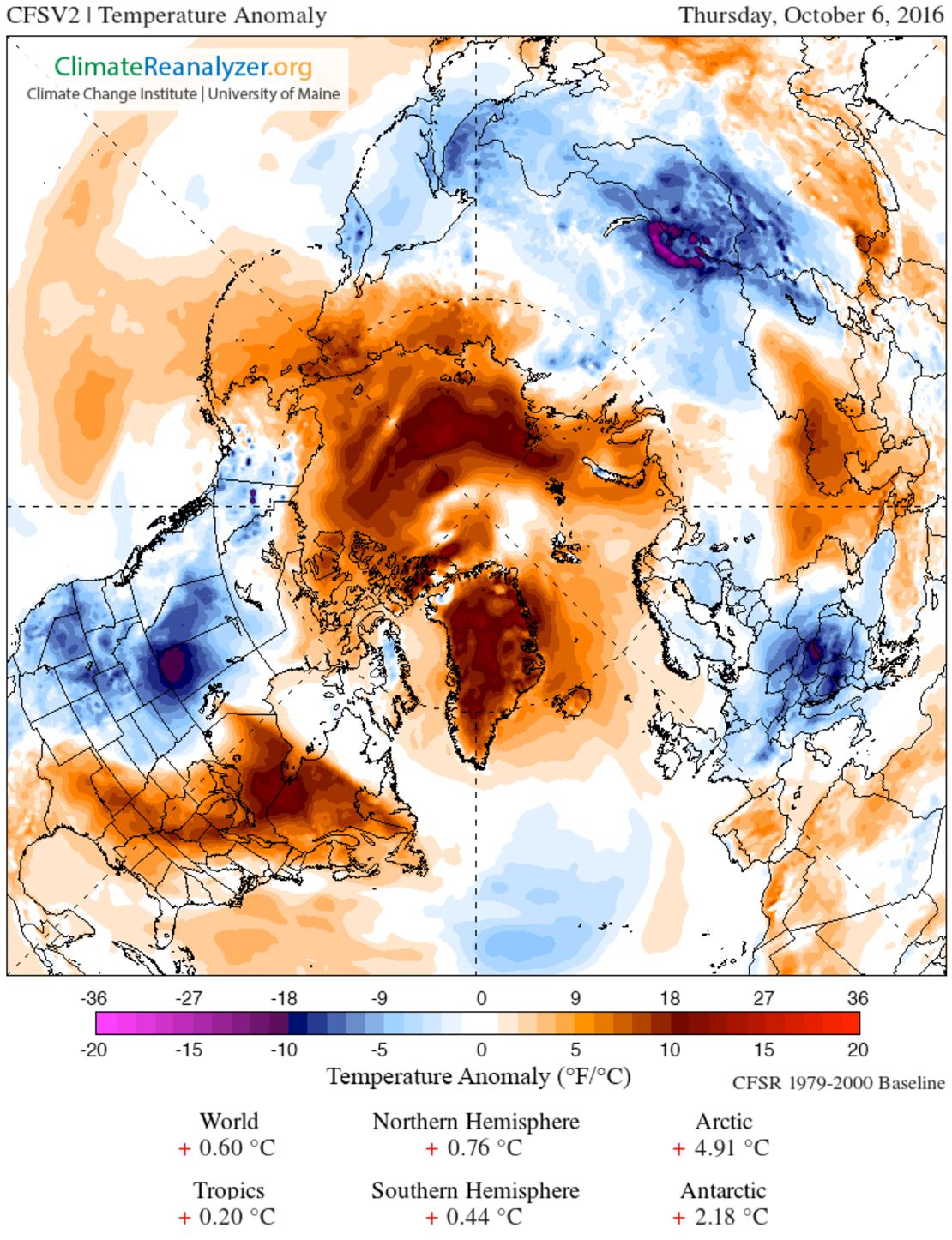

Temperatures are 30 degrees above normal at the North Pole

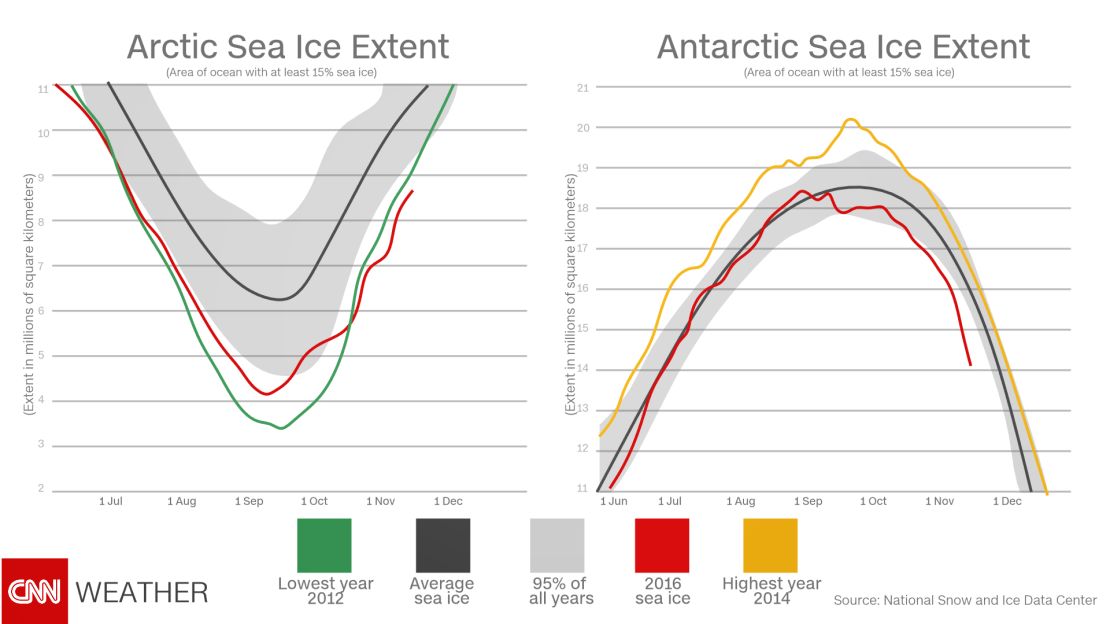

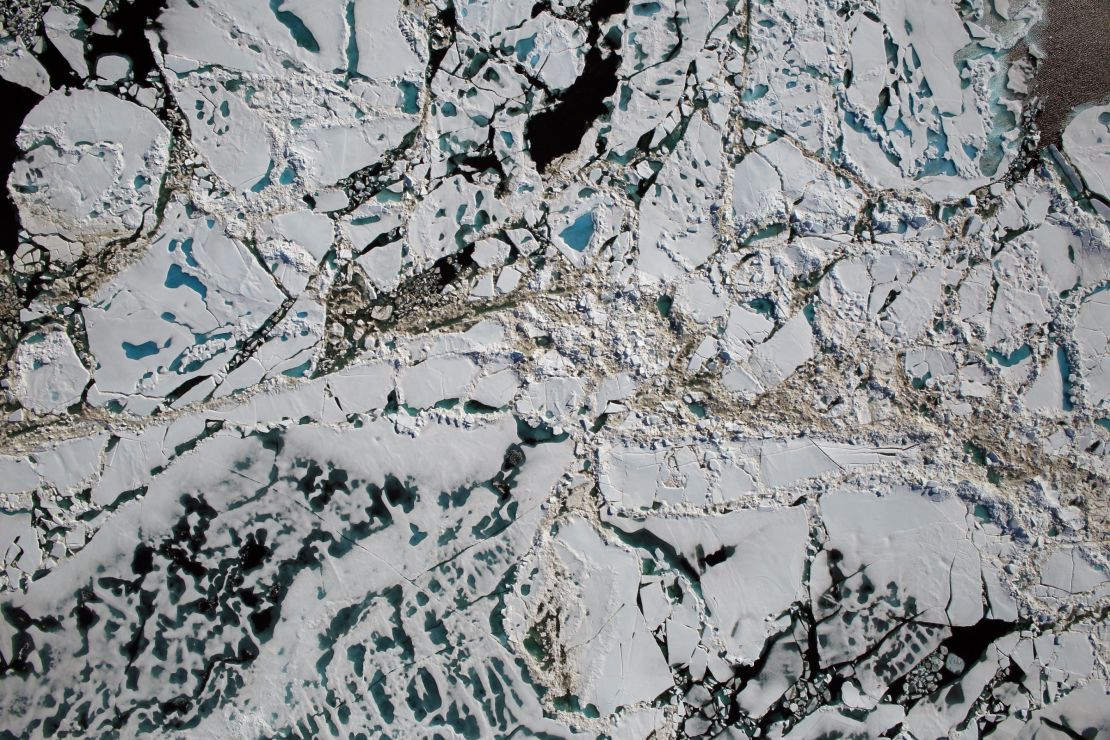

For what appears to be the first time since scientists began keeping track, sea ice in the Arctic and the Antarctic are at record lows this time of year.

“It looks like, since the beginning of October, that for the first time we are seeing both the Arctic and Antarctic sea ice running at record low levels,” said Walt Meier, a research scientist with the Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, who has tracked sea ice data going back to 1979.

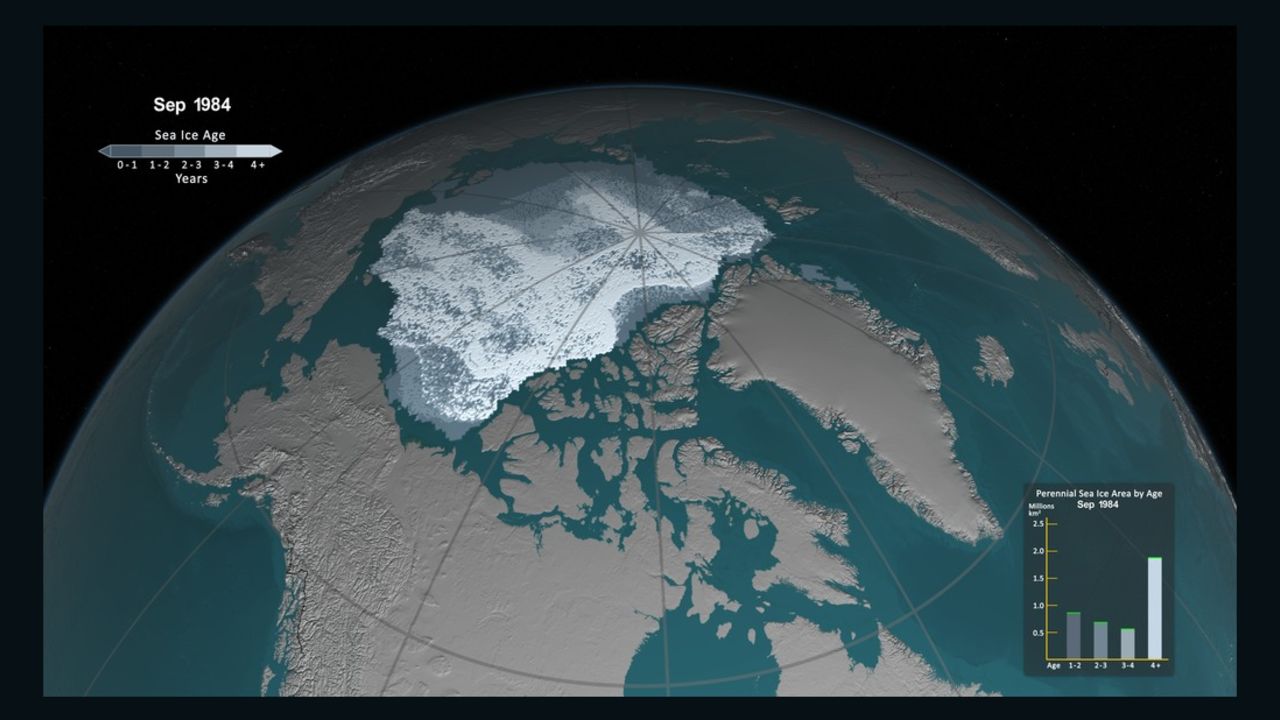

While record low sea ice is nothing new in the Arctic, this is a surprising turn of events for the Antarctic. Even as sea ice in the Arctic has seen a rapid and consistent decline over the past decade, its counterpart in the Southern Hemisphere has seen its extent increasing.

In fact, each year from 2012 through 2014 reached a record high for Antarctic sea ice extent. Skeptics have long pointed to ice gain in the Southern Hemisphere as evidence climate change wasn’t occurring, but scientists warned that it was caused by natural variations and circulations in the atmosphere.

While it is too early to know if the recent, rapid decline in Antarctic sea ice is going to be a regular occurrence like in the Arctic, it “certainly puts the kibosh on everyone saying that Antarctica’s ice is just going up and up,” Meier said.

The decline of sea ice has been a key indicator that climate change is happening, but its loss, especially in the Arctic, can mean major changes for your weather, too.

What’s going on in the Arctic?

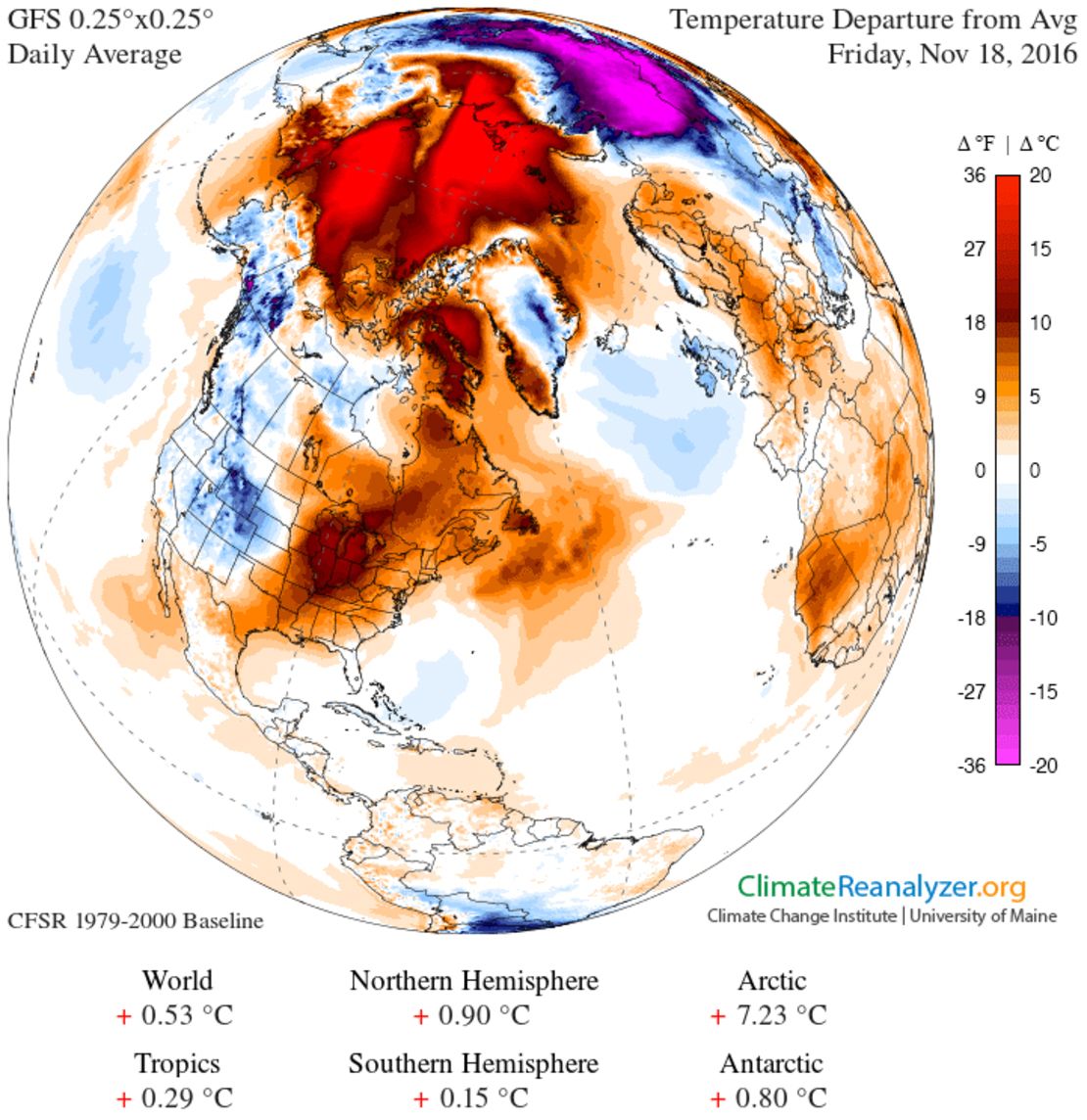

Temperatures in the Arctic have soared recently, and scientists are struggling to explain exactly why, and what the consequences will be. Air temperatures have been running more than 35 degrees Fahrenheit (20 degrees Celsius) above average.

At the same time, sea ice in the northern latitudes is at a lower level than ever observed for this time of the year. October and November are typically a time of rapid ice gain for the Arctic region, as daylight hours become shorter and shorter and eventually non-existent during what’s referred to as the “polar night.” Air temperatures plummet to below zero degrees Fahrenheit and parts of the Arctic Ocean not covered with ice quickly become covered. But this year, those air temperatures are staying much warmer, closer to the freezing mark of 32 degrees Fahrenheit.

To make matters worse, the water temperatures in the Arctic Ocean are several degrees above average, which is an expected result of having less sea ice. With less ice in the summer, more of the sun’s rays can heat the darker water, as opposed to being deflected back into space by the white ice cover. The result is a feedback loop, and one that scientists have warned about for some time.

“The interaction between Arctic ocean temperatures and the loss of ice formation leading to continuing record minimums is clearly a climate change signal,” said Thomas Mote, a geography research professor at the University of Georgia.

As it becomes clearer that the entire climate system in the Arctic, and potentially the Antarctic, is changing rapidly, the question now is what the impacts will be.

Why does it matter to us?

When it comes to the weather in the Arctic, it’s the anti-Vegas, Meier said: “What happens in the Arctic DOES NOT stay in the Arctic.”

The Arctic region impacts the weather in the rest of the planet – in particular, North America, Europe and Asia.

During the Northern Hemisphere’s winter, the arctic cold regularly “spills out” into the continents and can usher in major cold air outbreaks with crippling snow and ice storms, along with dangerously cold temperatures. Usually, this is regulated by the polar vortex that circles the North Pole several miles up in the stratosphere – not to be confused with the “polar vortex” nickname that’s been attached to every cold snap and snowstorm in recent years.

Join the conversation

Any change in the polar vortex would mean a change in the frequency and intensity of winter storms in the areas where most people live.

Researchers are looking at one such theory, which considers a warm Arctic and cold continents – basically, a warmer Arctic featuring less sea ice that leads to more frequent spilling of cold air that’s normally trapped by the polar vortex. That would mean the continents are hit with more frequent shots of Arctic air. Even though that Arctic air might not be as cold as normal, it is still plenty frigid to wreak havoc on populated places, locking them into long cold spells and major snow storms.

There’s a classic example of it happening right now. Large swaths of Europe and Asia have seen bitter cold and record snows over the past several weeks, all while the Arctic was bathing in temperatures 30 degrees Fahrenheit above average.

It’s far too early to tell if what we are seeing in the Arctic, and now the Antarctic, is a sharp shift towards warmer poles with less ice. Scientists are quick to point out that weather in these regions can change quickly, but this is another expected result of climate change. And enough examples can become trends – and trends can have consequences.