Story highlights

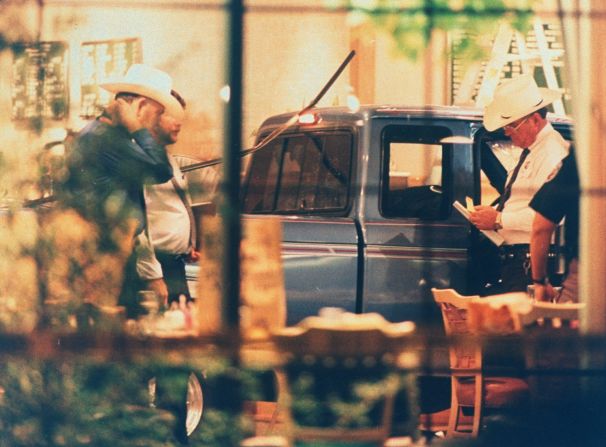

A new documentary, "Tower," revisits the University of Texas Tower sniper who killed 17 people in 1966

Mass shootings have been on the rise, both in frequency and lethality, while overall crime is declining

By now, it’s a tragically familiar storyline.

An angry, armed white man unleashes a hailstorm of bullets on a group of random innocents, leaving behind carnage, shattered families and questions about how it could have been prevented.

Before Elliot Rodger, Adam Lanza and Columbine, before the customary procession of speeches, vigils, hashtags, rallies and calls for reform, there was Charles Whitman, the University of Texas Tower sniper who killed 17 people and wounded 30 in 1966.

A new documentary now in select theaters across the United States, “Tower” revisits the shooting 50 years and a few months after the actual August 1 anniversary – the same day the state’s campus carry law took effect (which lawmakers say was a coincidence).

Still, depending on your view, it’s hard to overlook the irony or the symbolism. The Texas Tower shooting wasn’t just the first mass school shooting, it was the first mass shooting of the modern era: random, public, unpredictable and “therefore, impossible to defend against,” said “Tower” director and UT graduate Keith Maitland.

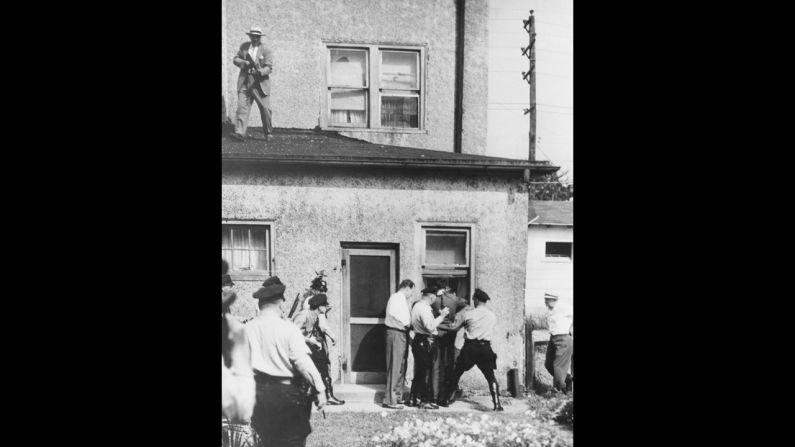

“At the time, no one involved had any context for this kind of attack,” Maitland said.

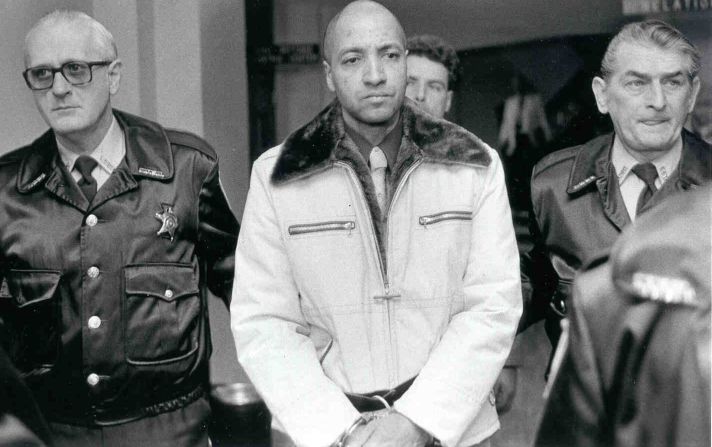

The United States has a long history of mass shootings, notes author Louis Klarevas, including the 1903 Winfield, Kansas, massacre that left nine dead and the 1949 Camden, New Jersey, murder spree that left 13 dead.

The UT Tower attack was the first mass shooting broadcast into the living rooms of American families through radio and television. As such, “it allowed Americans to experience mass murder in an unprecedented, quasi-direct manner,” said Klarevas, author of “Rampage Nation: Securing America from Mass Shootings.”

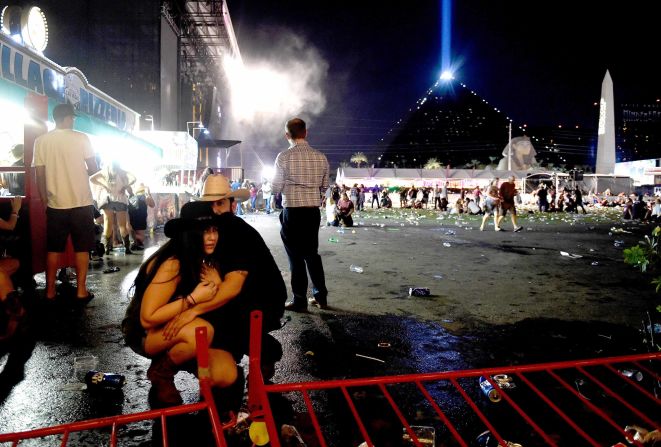

Since the UT Tower attack, mass shootings have been on the rise, both in terms of frequency and lethality. In fact, 2016 is on record as the deadliest year to date for mass shootings because of the Orlando nightclub attack, which itself is the deadliest shooting in American history. And, yet, overall rates of crime are declining.

To explain the dichotomy, experts have a few theories that underscore how much has changed since 1966, even as some things remain the same.

More people = more shooters = more shootings

The reason mass shootings are occurring with greater frequency can be partly explained by our growing population, Klarevas said.

“Quite simply, more potential shooters, more rampage shootings.”

And, people have access to high-powered weapons with large-capacity magazines that deliver fatal force without interruption, resulting in higher death tolls than before, he added.

“Quite simply, more bullets, more victims.”

Blame the Internet

Even if the Texas Tower attack was the first mass shooting of its kind, it’s a stretch to say it started a trend.

It would take another 30 years for mass shootings to start becoming as frequent as they are now. According to a report from the Congressional Research Service, there was an average of one incident per year during the 1970s, in which an average of 5.5 victims were murdered and two were wounded per incident.

That number rose to nearly three incidents per year during the 1980s (6.1 victims murdered, 5.3 wounded per incident); four incidents per year during the 1990s (5.6 victims murdered, 5.5 wounded per incident); four incidents per year during the 2000s (6.4 victims murdered, 4 wounded per incident); and four incidents per year from 2010 through 2013 (7.4 victims murdered, 6.3 wounded per incident).

What changed during that time? We got the Internet, for one thing, posits psychologist Frank T. McAndrew, a professor at Knox College in Illinois.

More often than not, shooters tend to be young men on the margins who feel like “disrespected losers” compared with the successful, attractive winners all over the Internet and social media, McAndrew said.

“The Internet makes it easier for us to feel like losers. We’re always comparing ourselves to others and obsessing over what we lack,” he said.

The same platform is a direct path to fame that attention-seekers can use to make a statement, he said.

“You know if you do it, you’ll be in the news; you’ll be a person of consequence.”

… and fame-seeking

Research shows that fame is also a compelling incentive.

“As a culture, America’s priority on fame-seeking at any cost and celebrity culture is much worse than it used to be,” said criminology professor Adam Lankford of the University of Alabama, author of “The Myth of Martyrdom.” For those obsessed with making it, mass violence can be a means to an end.

In a February journal analysis of mass shooters’ statements, Lankford makes the case that fame-seeking rampage shooters are more common in recent decades, more so in the United States than in other countries.

Decades of data show that on average, children born in the United States in recent years have “loftier expectations” of personal success, including fame and fortune, than previous generations, Lankford wrote in “Fame-seeking rampage shooters: Initial findings and empirical predictions.”

“When you have more people over time who want to be famous and this particular type of crime is the only way to guarantee you’ll be famous – unless you have exceptional skills or exceptional luck – that creates a deadly combination.”

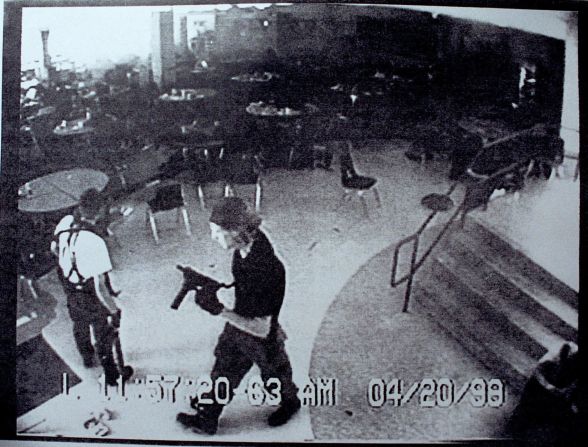

Though Adam Lanza and one other shooter have named Whitman as inspiration for their crimes, according to Lankford’s research, the killers most commonly cited as inspiration are Columbine High School shooters Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold.

Signs of progress

The fame-seeking copycat theories are compelling, given that not much else has changed in terms of causes of gun violence. Whitman is believed to have suffered from mental illness, just like many of today’s mass shooters.

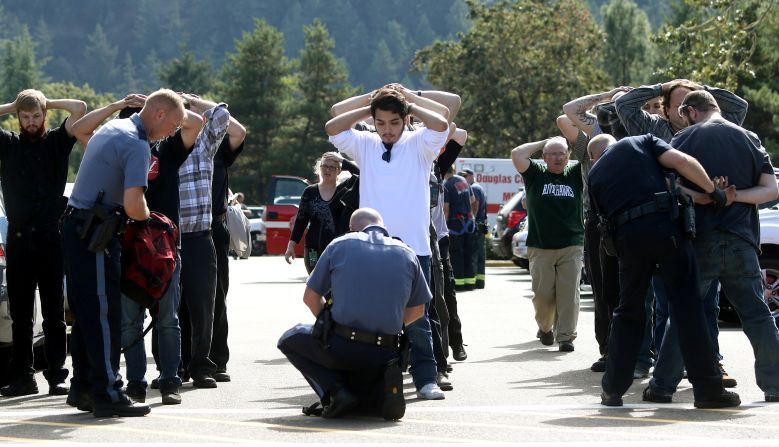

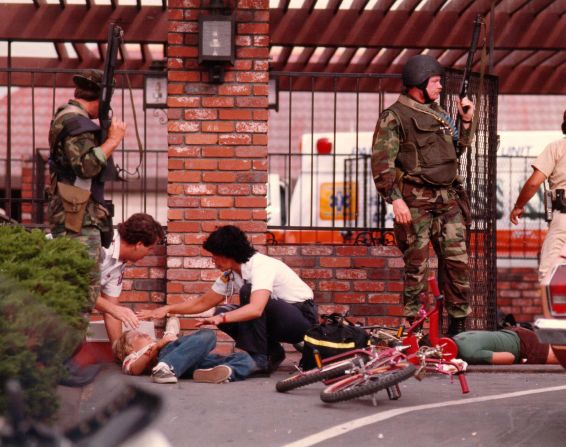

Otherwise, it’s impossible to say what could have prevented the Tower shooting, but it’s clear that law enforcement today are better prepared for these scenarios. They have advanced communication systems instead of hand-held radios, tactical training and weaponry – lots of it, too much for some people, Maitland believes.

Follow CNN Health on Facebook and Twitter

Other changes since Whitman’s time give Maitland hope. The one thing he heard over and over in dozens of interviews with witnesses and survivors was how they wished they had someone to talk to after the shooting.

“I think that’s a big change in the last 50 years. After mass shootings these days, there are grief counselors and all kinds of opportunities for individuals to approach their experience and work through the trauma via counseling and treatment.

“It’s incredibly difficult to process this kind of trauma. But I think that’s a definite sign of progress,” he said. “I wish there were more.”