Life for thousands of migrants at the sprawling “Jungle” migrant camp is set to be thrown into disarray – again – as French authorities renew efforts to dismantle the site on Monday.

The camp in Northern France has long been used as a gateway for migrants attempting reach the United Kingdom.

This time, French authorities say it will no longer be an option.

Here’s how we got here.

The ‘Jungle’

Known as the “Jungle” the camp is a sprawling migrant settlement situated in the port town of Calais.

The controversial camp serves as base for migrants hoping to cross into England through the 50 kilometer (31 miles) undersea Channel Tunnel that connects the two countries.

A strong French police presence, reinforced by UK border officers and heavily manned wired fences, attempt to thwart migrants’ journeys to Dover. Clashes with local authorities are a regular occurrence.

In September, the British government announced construction on a four meter (13 foot) high wall along the camp’s approach. The £17 million ($23 million) deal was struck between the UK and France to stop the flow of illegal immigration.

A risky passage

Many migrants risk their lives either by stowing away on a truck or a Channel Tunnel train.

In 2015, Channel Tunnel operator Eurotunnel intercepted 37,000 migrants attempting to travel to the UK illegally.

Thirty-one people died while trying to reach British soil last year, many of them teenagers and young adults, according to the International Organization for Migration.

Harrowing reports of fatal journeys also made headlines, including the death of an African teenager who was struck by an oncoming train.

So far this year, 15 migrants attempting a similar journey have died.

The population is constantly changing

It is hard to pinpoint exactly how many people live there as the camp does not qualify for refugee camp status under international law.

As a result, the “Jungle” exists in a legal gray area, lacking the infrastructure and authority to provide an accurate census.

Migrants are constantly coming and going, making it hard for charities and local authorities on the ground to provide up-to-date figures.

However, earlier this week the French government said there were between 5,684 and 6,486 migrants living in the camp. Aid organizations on the ground say the population is closer to 10,000.

War, famine, and violence drive migrants to Calais

The majority of the migrants living in the “Jungle” come from Afghanistan, Eritrea and Sudan.

Migrants from war torn countries such as Iraq and Syria are also there, along with Somalians and other Africans seeking political asylum, as well as displaced Kurds and Palestinians.

Men make up the majority of Calais’ inhabitants. Women only make up about 10% to 15% of the total population, and often live in separate areas.

A center has been created by French authorities to facilitate the migrant and refugees departure on Monday.

There will be four separate lines at the center to separate different groups: adults, minors, families and vulnerable people (pregnant women, the sick and the disabled).

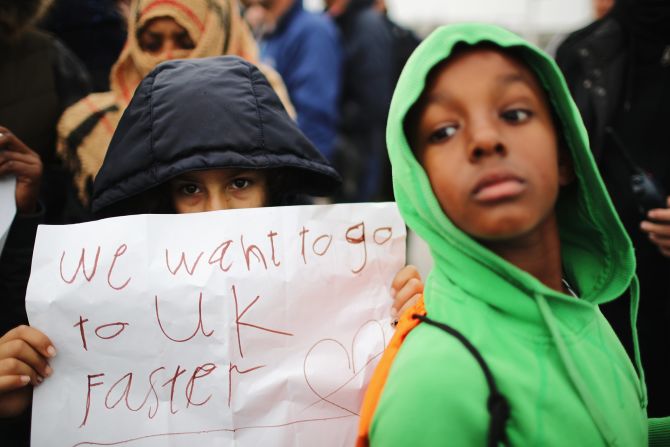

Unaccompanied children are of serious concern

There are 1,291 isolated minors currently in the camp, according to French aid organization Terre D’Asile. Some have fallen victim to human traffickers, with many exposed to sexual abuse. Malnutrition and disease are commonplace.

The UK has started to accept a small number of “qualified” children under EU and UK law. French authorities said Friday that special provisions are to be made for unaccompanied minors.

In March, the British government said it would allow 3,000 unaccompanied child refugees into the country. But so far this year, only 80 have been accepted from France; the first arrived earlier this month.

This is not the first time the ‘Jungle’ has been cleared

The saga of the Calais 'Jungle'

Although the population of the camp has swelled to its highest number in the past year, Calais has attracted thousands of refugees and asylum seekers for at least 17 years.

It was first closed in 2001, prompting a cycle of destruction and rebuilding between migrants and the authorities that have defined the camp ever since.

This March, the southern half of the camp was demolished. But by August, French authorities reported a 53% rise in the camp’s population over the course of two months – the biggest influx of migrants the “Jungle” has ever seen.

Why is it this new clearing happening?

Earlier this month, French President Francois Hollande announced the “full and final” dismantlement of the camp.

As it’s an unofficial camp, the “Jungle” does not qualify for international assistance. There are not enough funds or manpower to keep sanitation and security under control.

Migrants’ basic needs are often addressed by charities and NGOS working on the ground. And although these organizations provide vital, daily assistance, their work is not a permanent solution.

The closure comes at a time that Europe’s growing immigration crisis, fear of terrorism and the spread of anti-migration movements have soared.

The plan is to have the camp completely torn down by December, according to the French Ministry of the Interior.

Could another ‘Jungle’ grow?

French authorities have said the migrants and refugees will be given two options: to seek asylum in France and be relocated within the country or to return to their country of origin.

If relocated within France, they will be moved to temporary accommodation in a shelter while their claim is processed.

In the past year alone, up to 6,000 Calais residents have been moved to other locations in France, where 80% have applied for asylum.

Some charities working inside the camps say that although the proposed living arrangements are a suitable alternative for those seeking asylum in France, the solution is not viable for many who wish to settle in the UK.

“Many refugees in Calais have strong reasons for wanting to get to the UK and will simply return to Calais,” charity Care4Calais said.