It’s the last state flag to feature the Confederate battle emblem, and for a moment after the 2015 Charleston shootings it seemed like its days were numbered.

Several municipalities in Mississippi removed the state flag from government property in the wake of the Charleston, South Carolina, shooting that left nine African-American churchgoers dead. So did the University of Mississippi – no small gesture for a school steeped in tradition – and Gov. Phil Bryant’s alma mater, the University of Southern Mississippi.

Republican House Speaker Philip Gunn publicly supported changing the flag, prompting state lawmakers to put forth 21 pieces of legislation proposing ways both to make it happen and prevent it.

Then, the movement appeared to lose steam.

None of the legislation made it out of committee, culminating in what opponents of the flag saw as a repudiation of their efforts when Bryant issued a proclamation designating April as Confederate Heritage Month.

Tuesday, opponents of the flag sought to recapture that momentum with a rally in front of the U.S. Capitol. “Take It Down America” was organized to bring attention to a federal lawsuit arguing the flag incites racial violence and infringes upon the 14th Amendment protections for black residents.

Mississippi attorney Carlos Moore told CNN in April that he filed the lawsuit after the Legislature failed to act on bills proposed in the wake of Charleston. Hence the choice of Washington as the rally’s setting on Flag Day, said actress and rally co-organizer Aunjanue Ellis, who lives in the Mississippi city of McComb.

“The fact that a state in our country is allowed to carry the emblem of a foreign country, one used by terrorist organizations, is unacceptable,” she said.

Of course, not everyone in Mississippi shares her view of what the flag stands for, making it the last holdout in the battle over state-sponsored Confederate symbols. To many it’s a symbol of Southern pride that’s been misappropriated by hate groups, tarnishing its legacy. Some say it’s only a matter of time before the symbol is removed; if that’s the case, what will it take for change to come to Mississippi?

‘The flag is not evil’

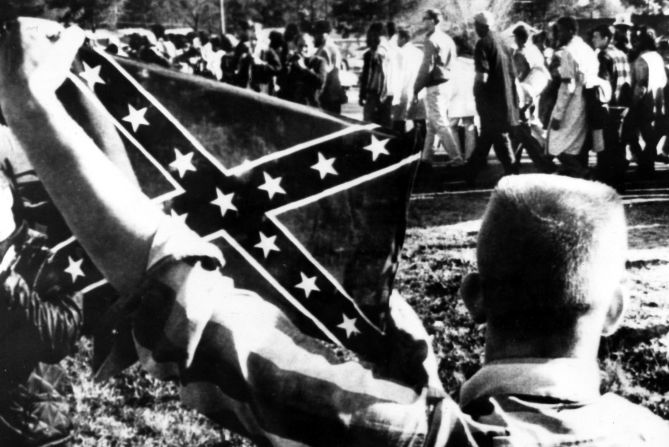

The debate has ebbed and flowed since the civil rights era. The Charleston shooting revived the discussion nationwide amid evidence that the massacre was racially motivated. Images of accused shooter Dylann Roof with the Confederate battle flag fueled the controversy, even as flag supporters were quick to condemn him and any acts of violence purportedly carried out in the name of their heritage.

“The flag is not evil. Some people who used it were evil. But that doesn’t mean we should get rid of it,” said Marc Allen, spokesman for the Mississippi Division of the Sons of Confederate Veterans. His group supports keeping the flag, known in the state as the 1894 flag for the year it was introduced.

After South Carolina lawmakers voted to permanently remove the flag from statehouse grounds, other states began to take up the issue. Alabama Gov. Robert Bentley directed that four Confederate flags be taken down from a Confederate memorial at the state capitol so they would not distract from legislative issues. Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe ordered an end to Sons of Confederate Veterans specialty license plates that, like Georgia’s and Tennessee’s, featured the Confederate emblem.

Local battles over Confederate monuments sprang up in New Orleans, Baltimore, Louisville and Charlottesville. The U.S. House voted in May to ban Confederate flags from national veterans cemeteries except on two days: Memorial Day and Confederate Heritage Day in states that observe it. Tuesday, the Southern Baptist Convention urged its members to “discontinue the display of the Confederate battle flag” as a sign of solidarity with their “African-American brothers and sisters.”

Mississippi seemed poised to act on the state flag after Speaker Gunn spoke out on the issue, saying “As a Christian, I believe our state’s flag has become a point of offense that needs to be removed.” Cities including Macon, Columbus, Grenada, Magnolia, Hattiesburg, Clarksdale, Starkville, Yazoo City and Greenwood voted or issued executive orders to remove the state flag; others, including Petal and Gautier, voted to keep it.

Legislative proposals ranged from appointing a commission to design a new flag to making the Magnolia flag, which preceded the current design, a second official flag. On the other side of the debate, lawmakers proposed requiring the state flag be flown on government property and withholding public funds from public colleges and universities that don’t display the flag.

Observers say a lack of political leadership in Mississippi’s Republican-led House and administration on the issue is maintaining the status quo in the state despite growing national sentiment against symbols of the Confederacy.

Ellis has become the public face of the fight by penning passionate op-eds and using award show red carpets to spread her message through fashion statements. Her family has deep roots in Mississippi; she was born in San Francisco but raised in Mississippi in the same home where her mother grew up.

To her, the Confederate emblem is a symbol of racism that does not represent modern-day Mississippi. After staging a handful of rallies this year in the state capital of Jackson, Ellis and her allies brought their fight to Washington in an attempt to frame the debate as a national issue, she said.

“This is about America making a decision about who it is,” Ellis said.

‘History deserves study’

It’s a controversial stance, seeing as state flags tend to be regarded as symbols of just that — the state and its residents, not the country on the whole. Mississippians on both sides of the debate believe it’s an issue to be resolved by residents of the state, not outsiders.

And, as Bryant and supporters of the current flag point out, residents of the state have already made their opinion clear on the issue.

In a 2001 referendum, 65% of Mississippians voted to keep the Confederate emblem instead of replace it with 20 white stars on a blue field to represent Mississippi’s status as the 20th state.

Bryant did not respond to CNN’s repeated requests for comment. He has not publicly taken a hard line one way or the other, but he has said that if it were to happen it should be decided by the people in a vote.

His explanation for Confederate Heritage Month offers some insight into his views on Confederate legacy. But it’s hard to draw conclusions for what that means for the flag.

“Gov. Bryant believes Mississippi’s history deserves study and reflection, no matter how unpleasant or complicated parts of it may be,” spokesman Clay Chandler said in February. “Like the proclamation says, gaining insight from our mistakes and successes will help us move forward.”

‘Anything can be hateful’

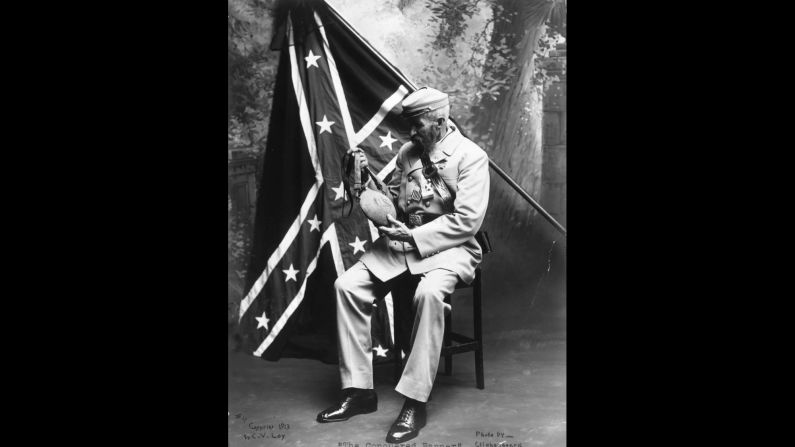

The Confederate battle emblem has been on the state flag since 1894, when it replaced the flag featuring the state tree, a magnolia, on a white field.

Opponents of the 1894 flag point to the circumstances under which it came to be as evidence of its divisive legacy. Proposed at a time when the state did not have an official flag or coat of arms, a joint legislative committee recommended the design at the request of Gov. John Marshall Stone, according to the Mississippi Historical Society.

Though their recommendation made no explicit reference to the Confederacy, the symbolic undertones were apparent during the Reconstruction era, when Jim Crow laws that codified segregation were instituted across the South.

Or, at least, that’s one interpretation. Supporters of the 1894 flag say it honors those who fought for the Confederacy, not the Ku Klux Klan and hate groups that have appropriated it for their own causes.

Many who fought under the Confederate banner were fighting for their land, their families and their homes, not explicitly for the cause of slavery, said Allen of the Sons of Confederate Veterans.

“Anything can be hateful if you want it to be. It depends on how you want to interpret it,” he said.

The group is in the process of collecting signatures for a proposed ballot initiative that would amend the state constitution to recognize the current flag. The measure would effectively make it the state flag by law, requiring a constitutional amendment to ever change or modify it.

Making it the official state flag through a constitutional amendment would keep the decision “out of the hands of politicians,” he said.

“The flag has been misused over years to support causes of hate groups. Yes, the KKK used it. But by saying that because hate groups used it we should get rid of it, by that logic we should get rid of the U.S. flag and the Christian cross since the KKK used them, too.”

If flags reflect history and the people who designed them, at what point do they change to reflect contemporary values?

‘Seizing an opportunity’

In October, the University of Mississippi student government decided the time had come for their campus. Student senators voted 33-15, with one abstention, to ask the school administration to furl the banner. To the surprise of many, the administration obliged.

The flag was furled in a formal ceremony and preserved in the University Archives along with resolutions from students, faculty and staff calling for its removal.

“I understand the flag represents tradition and honor to some. But to others, the flag means that some members of the Ole Miss family are not welcomed or valued,” then-Interim Chancellor Morris Stocks said. “Our state needs a flag that speaks to who we are. It should represent the wonderful attributes about our state that unite us, not those that still divide us.”

The way it happened is a model for how the flag issue should be approached, said Ole Miss history professor John Neff.

“Every generation of students on this campus has made the campus their own. This was true in the 1890s, so why shouldn’t it be true now?” he said.

“Our campus is now more diverse in every way that you can apply the word diverse,” he said, referring to the student body’s growing African-American population, which accounts for about 3,200 of the school’s 25,000 students, or nearly 8%.

“They’re seizing an opportunity to make the campus their own, just as previous generations have done,” he said. “They’re making a different statement because they’re different and that should not be pushed aside because of prior generations who never want the university to change.”

Student senator Andrew Soper, who organized a petition that drew more than 1,800 signatures (at least 1,500 of which came on the day of or after the vote) urging Ole Miss to keep the flag, said he was disappointed to see the flag taken down.

“I think it’s the wrong move. They should have done it through the state of Mississippi. They didn’t do it the right way,” he said.

‘Others have a heritage, too’

Lawmakers such as Sen. John Horhn attempted to change the flag through several legislative attempts. He proposed appointing a committee to create a new flag and tabled a measure to put it to a voter referendum, among other means.

Given the “national sentiment” expressed last summer from all walks of life, he thought the political will might finally exist in Mississippi to retire the flag. Because the Legislature only meets for first three months of the year, Gov. Bryant, up for re-election in 2015, could have called a special session after the Charleston shootings to take up the issue, Horhn said.

And yet he didn’t. Then, other controversial legislation took center stage, including a religious freedom bill that allows organizations and businesses to deny certain services to the LGBT community and a $415 million budget reduction that cut funding for services “that affect poor people,” Horhn said.

“The enthusiasm did not reach the hearts and souls of our top political leaders, especially those on the Republican side of the house,” he said.

To Horhn, who is African-American, the reason is clear: “Racism is still very much a part of the fabric of Mississippi,” permeating policy decisions big and small.

“We have not come to terms with that issue especially as it relates to black and white relationships,” he said.

The flag issue is a perfect example, he said. The inclusion of a Confederate symbol is a “slap in the face” to most African-Americans in the state, who make up 38% of the population.

“I understand that some people might see it as part of their heritage but I don’t buy into the concept that it should be the heritage of the state. Others have a heritage, too, and that flags contradicts a lot of feelings about what our heritage ought to be.”

He blames the Republican super-majority, in particular, the House speaker, who talked the talk but failed to walk the walk, in Horhn’s view.

“The problem in Mississippi is we have too many elected officials who are followers and not enough who are leaders,” he said.

But Gunn is not backing down from the issue, spokeswoman Meghan Annison said. Just because nothing got out of committee this session does not mean the fight is over, she said in an email.

Gunn stands by what he said in February after a slew of bills failed to make it out of committee, blaming the deadlock on a failure to reach a consensus among lawmakers.

“For anyone to suggest I have surrendered or backed up on my position of changing the flag is simply not true,” Gunn said then. “I have not wavered in my viewpoint that we need a different flag to represent Mississippi. I have spoken with many House members, both individually and collectively, and have tried to convince them to adopt my view.

“I will continue to stand by my view that changing the flag is the right thing to do,” he continued. “The flag is going to change. We can deal with it now or leave for future generations to address. I believe our state needs to address it now. I am disappointed that nothing took shape this year, but I will continue this effort.”

Change takes time, Annison said.

“The state of Mississippi’s current flag has been in place since 1894. Speaker Gunn understands time and work are needed to help properly address the best approach to making the changes needed regarding the current state of Mississippi flag.”