Editor’s Note: The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a longtime civil rights activist, is the founder and president of the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.

Story highlights

Rev. Jesse Jackson says we ride on the shoulders of Muhammad Ali, a fighter for justice who stood up to racism and won

He recalls Ali's stance against the Vietnam War, which for a time cost him his career

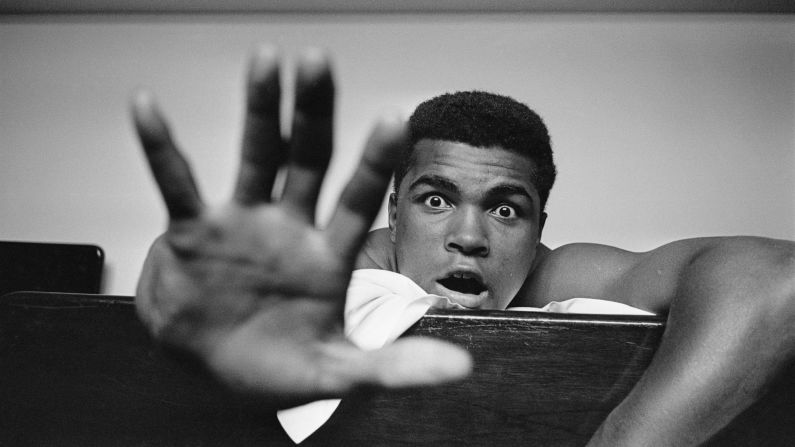

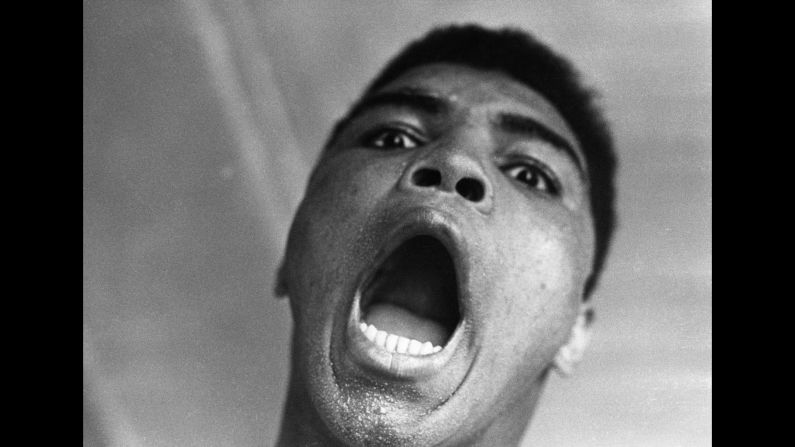

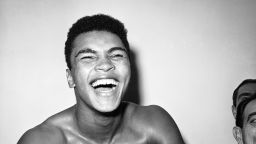

After his death was announced late Friday night, I watched on a television in the San Francisco airport as the screen filled with images and sounds of the young Muhammad Ali. He was beautiful to watch. Then one of the pundits opened his mouth. He said Ali was “controversial.” I shook my head and said to myself, “No, buddy, you got it all wrong.”

Ali was not controversial. Segregation was. Black soldiers forced to sit behind sniggering Nazi prisoners of war on American military bases was controversial. Having to pay taxes but not being allowed to vote – controversial. No, Mr. Pundit, resisting evil was not controversial. It made perfect sense. That is what Ali did his entire life.

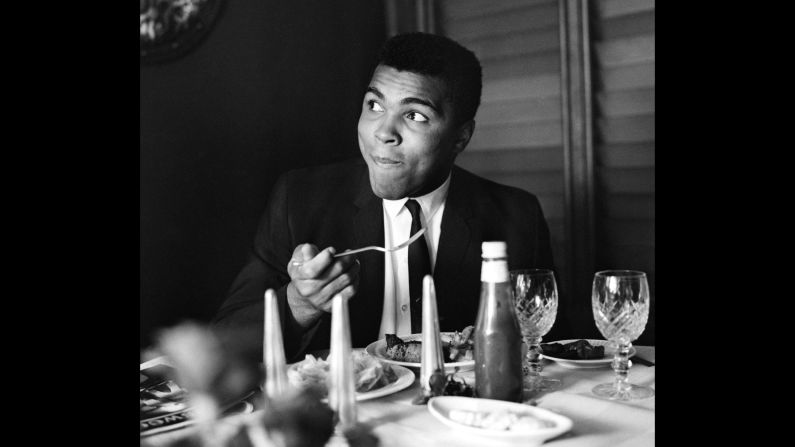

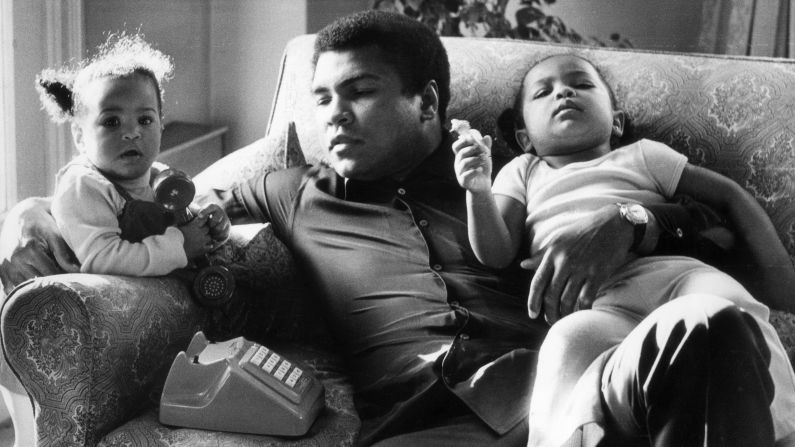

Ali and I were born four months apart, sons of the South, survivors of American apartheid. I’m the older one. Over the decades, the “people’s champ” has been a source of endless pride and inspiration to me, a role model in the freedom struggle.

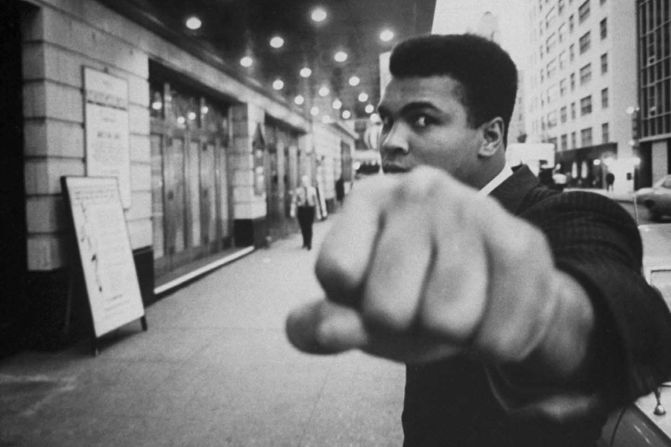

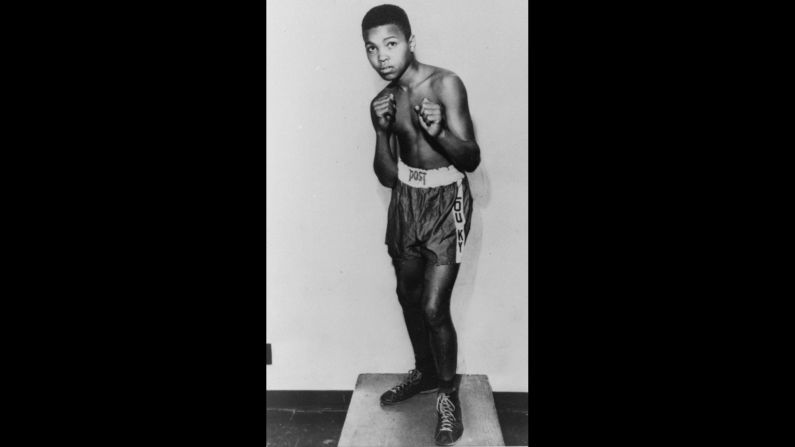

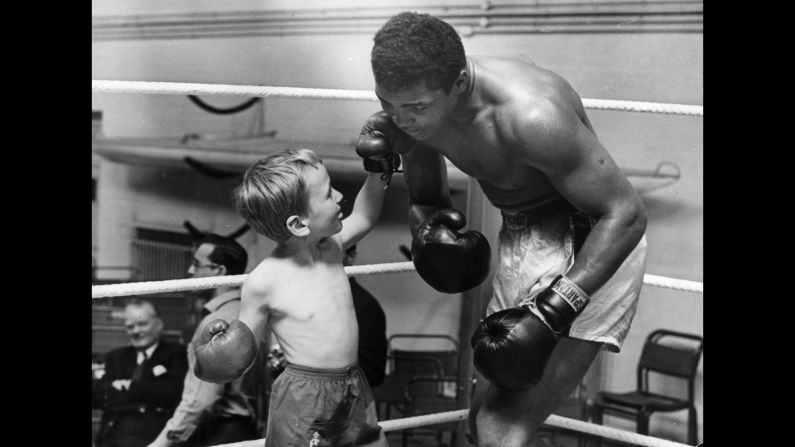

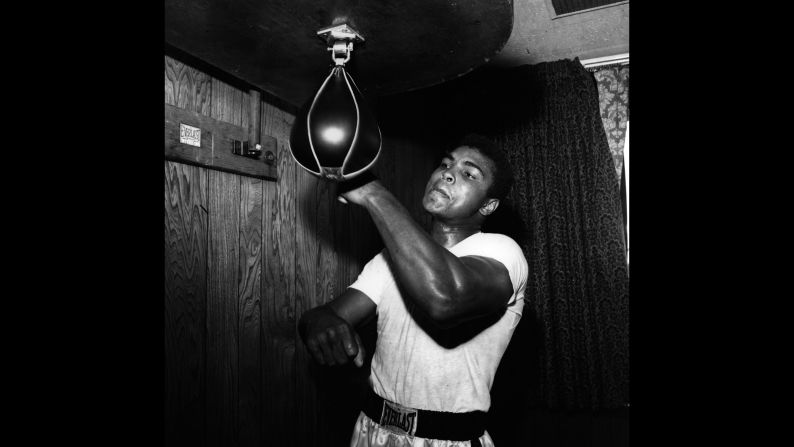

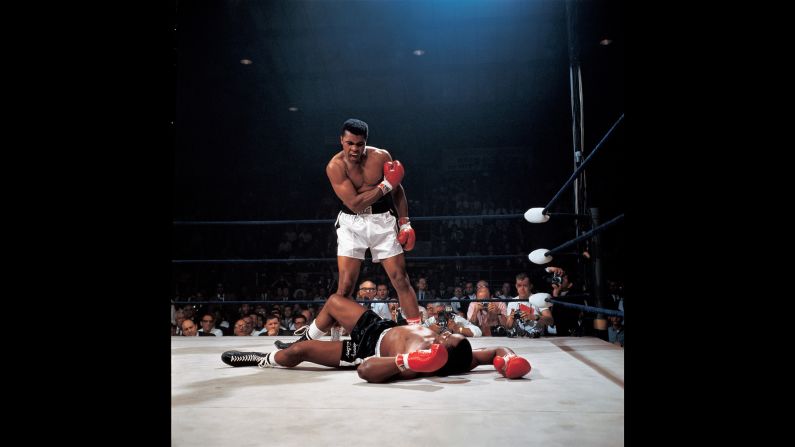

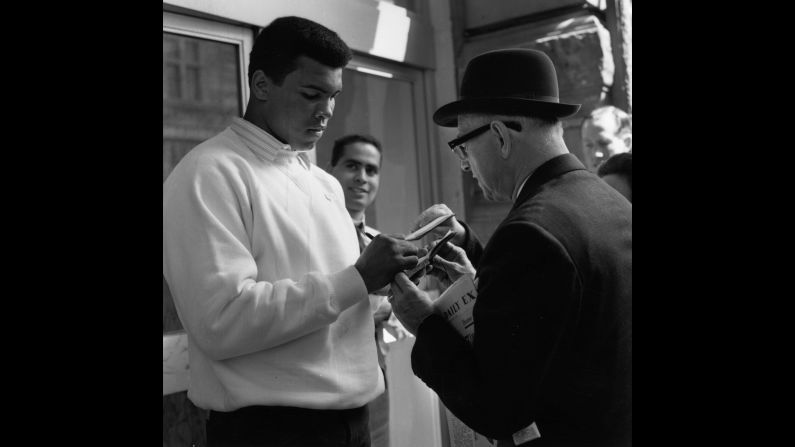

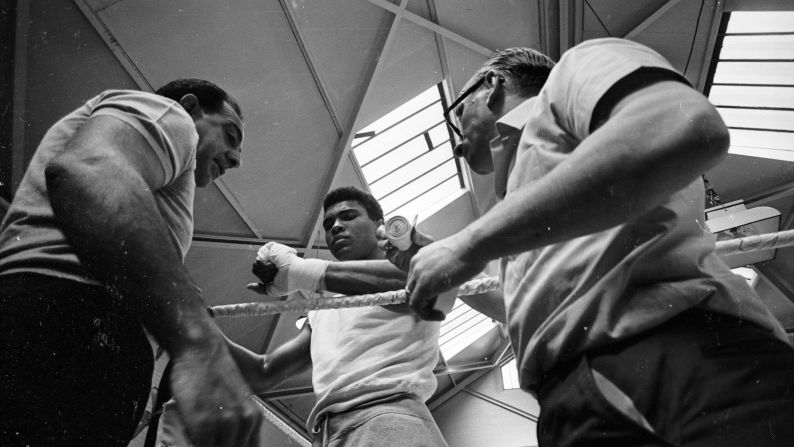

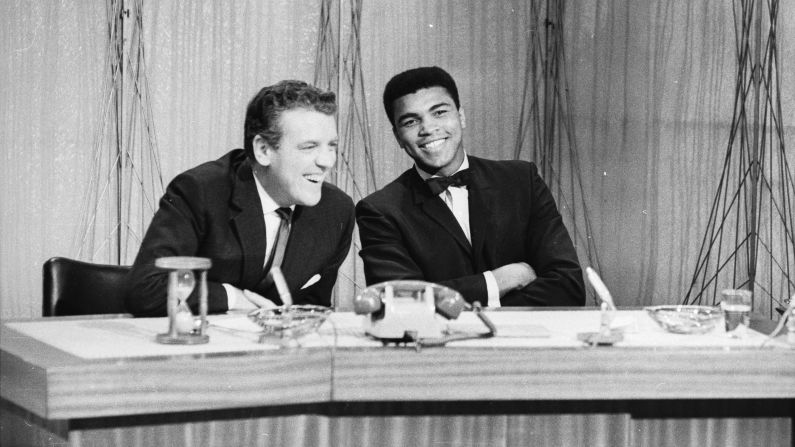

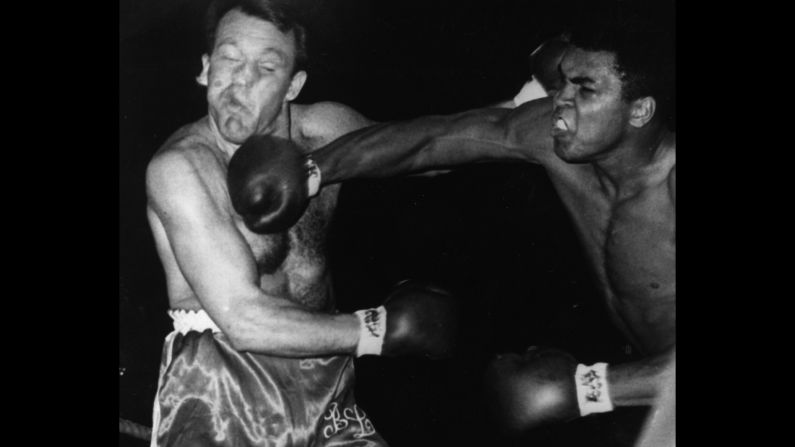

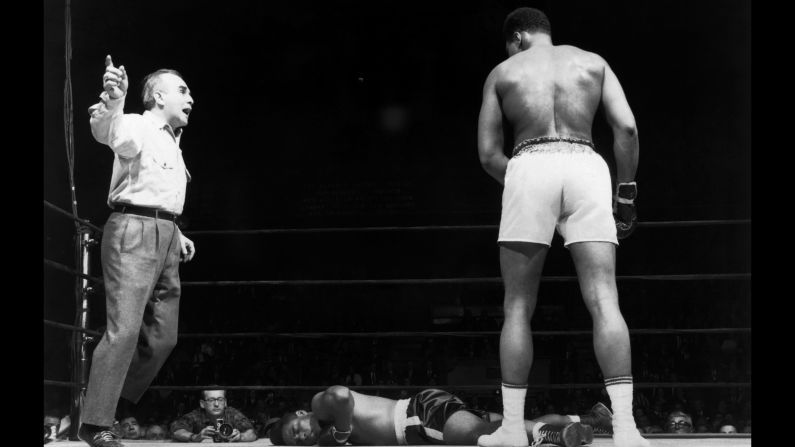

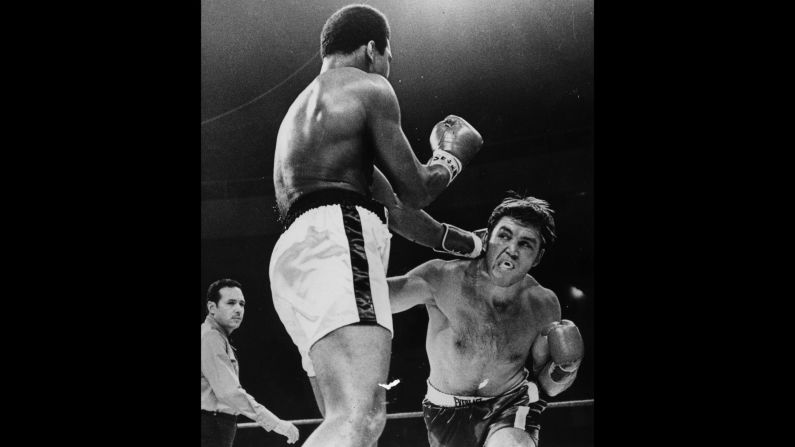

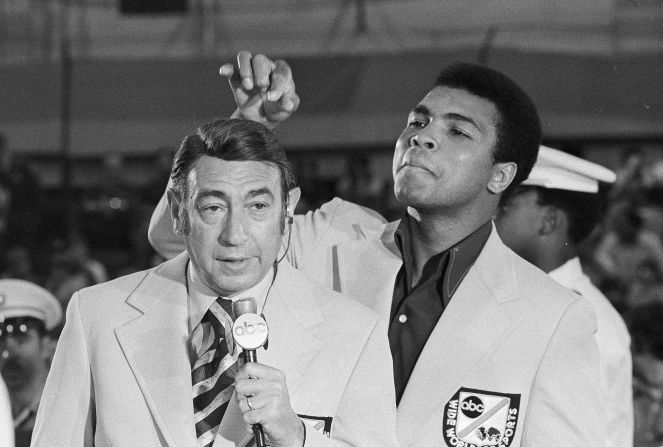

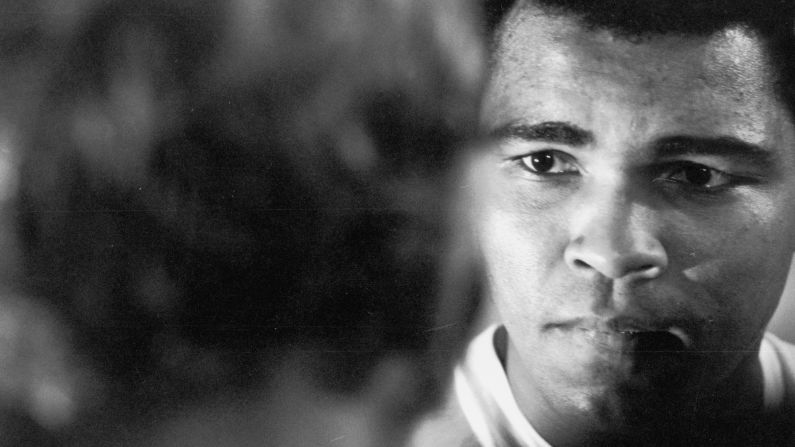

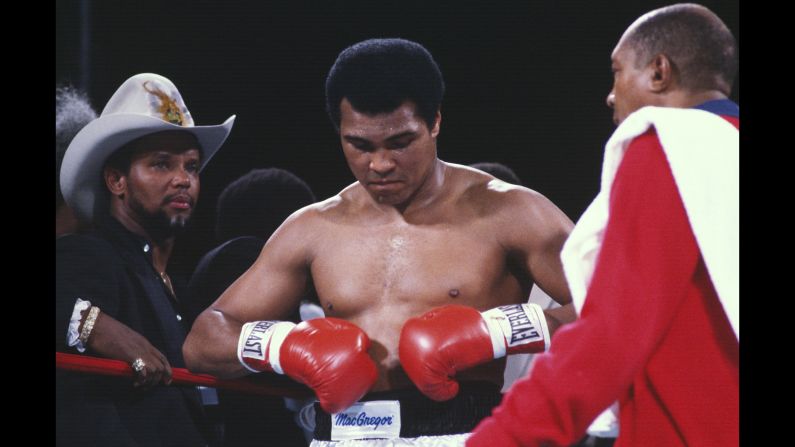

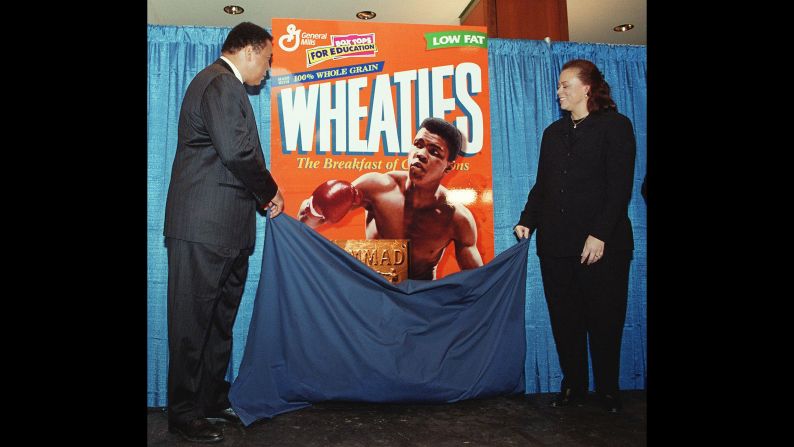

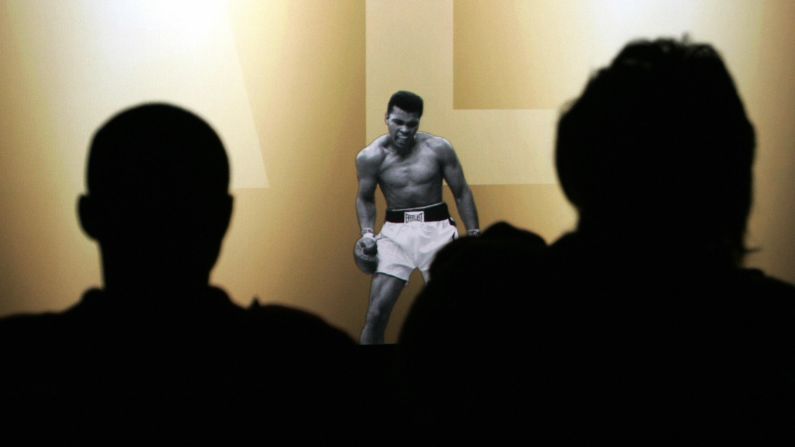

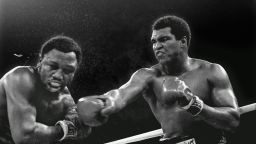

No one had seen – or heard – a boxer like Muhammad Ali before. Or since, I might add. With speed and grace, power and courage – and a poem or two – he dominated the sport inside and outside of the ring. He’s the guy who made the most money and lost the most money but gained his soul in his sacrifice for peace over war and dignity over dollars.

As he so famously said, to explain why he refused induction into the military, no Viet Cong had ever called him the N-word. Indeed, he did not have to travel 10,000 miles across the world to hear that epithet. In the early 1960s, from Texas across to Florida and up to Maryland, African-Americans could not use a public toilet, we could not eat at restaurant along the highway, we could not breathe.

Most people adjusted. Most people said nothing, they found their place, swallowed their resentment, their contempt, their anger.

Muhammad Ali was not most people. Neither was Rosa Parks nor Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

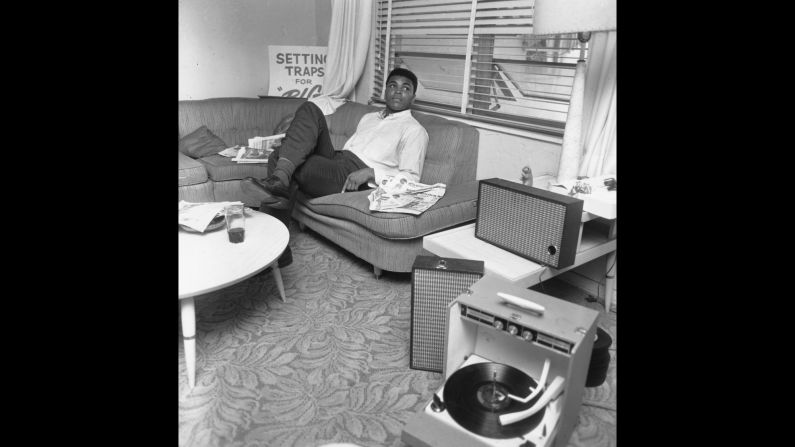

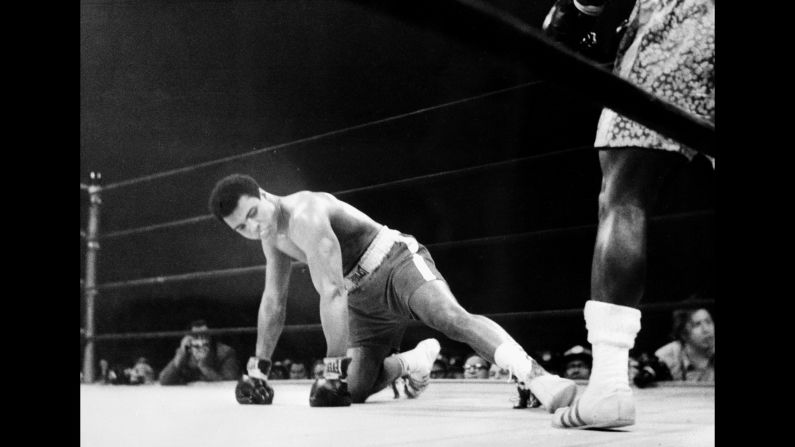

Ali was radically maladjusted to a system that did not make any sense. He resisted. He identified with the black liberation struggle. Those who made us better paid the price. Medgar Evers paid with his life. Ali gave up his career. These are veterans of domestic war.

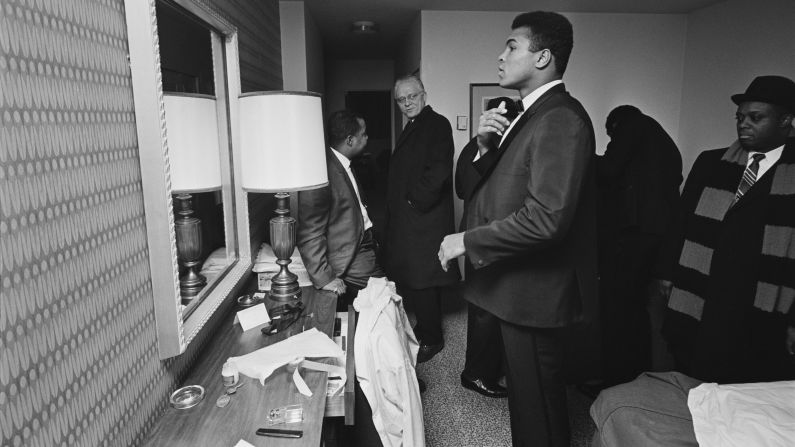

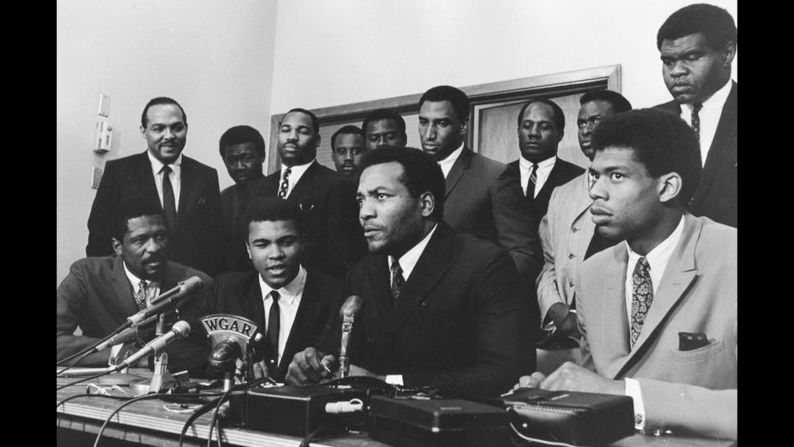

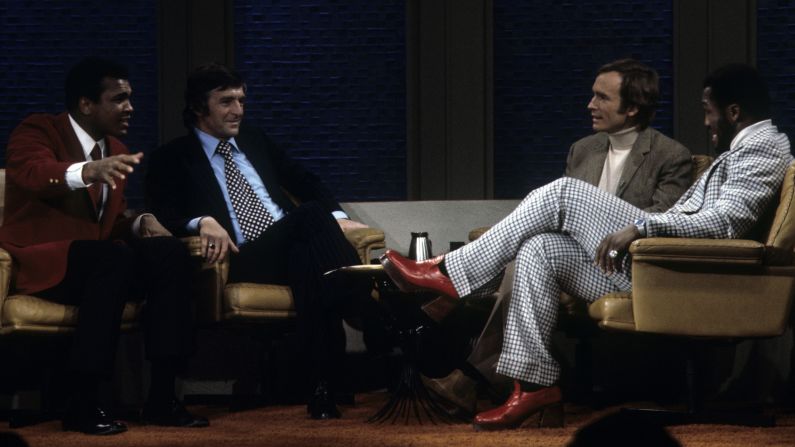

On April 4, 1967, as Dr. King prepared to give his famous anti-Vietnam war speech at Riverside Church, I joined Andy Young and a few others in Dr. King’s hotel room in New York City. In walked Jim Brown and Ali. We laughed and embraced and hunkered down to talk about war and peace. Their powerful presence boosted our morale. The government had the most powerful military in the world. We had the champ.

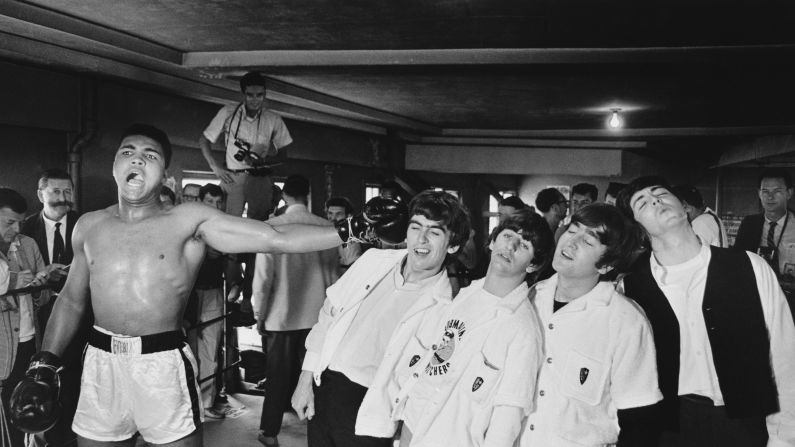

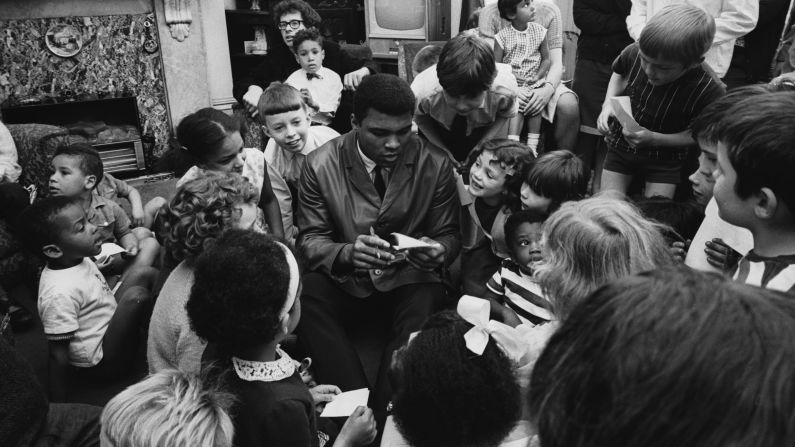

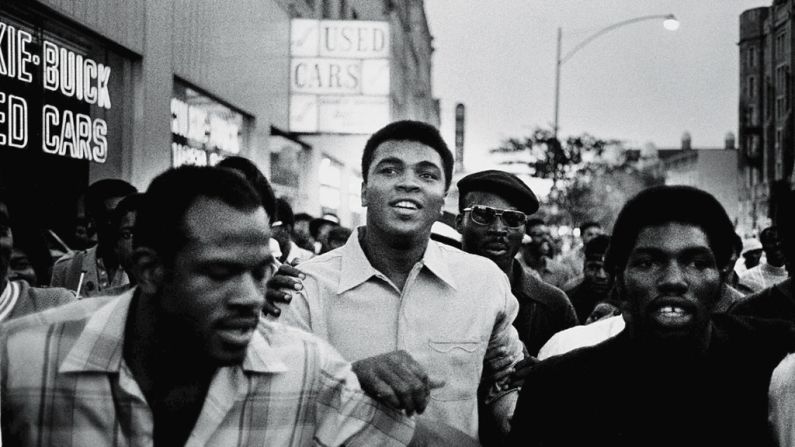

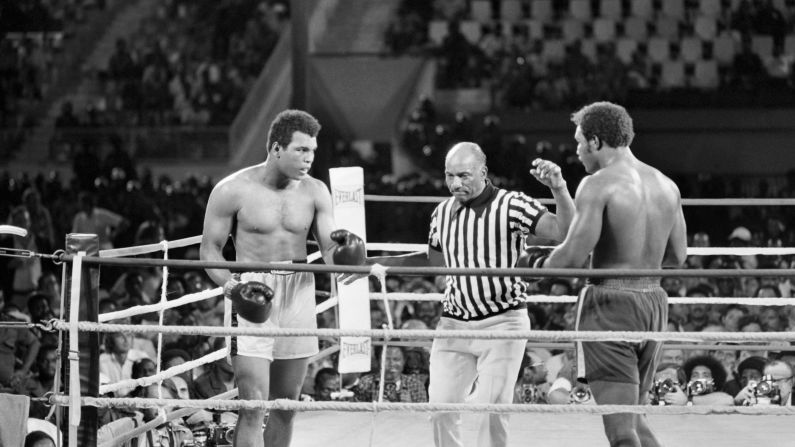

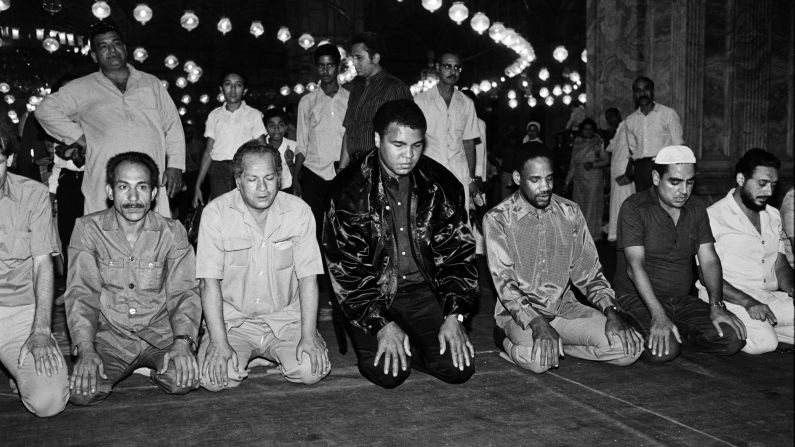

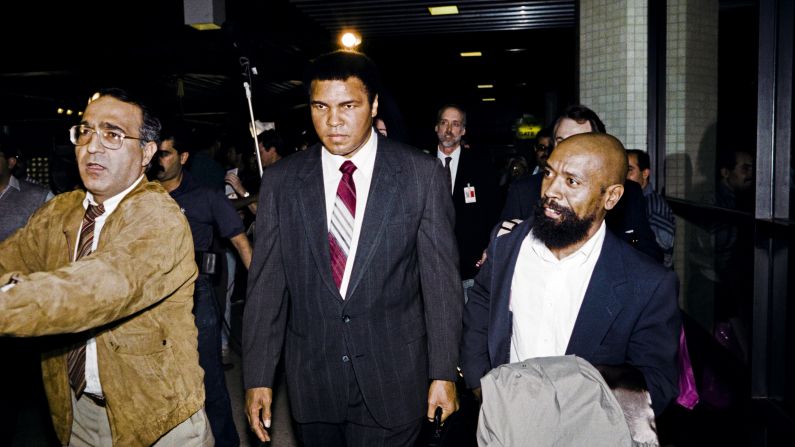

Ali was bold and brave, a bad man, pretty as a girl, as he liked to say. He affirmed the beauty of blackness. He saw himself as a global citizen, a true world champion. Once he regained the right to fight, to make a living, after three years wandering in the wilderness, Ali took his light to many places often forgotten and shunned. He fought in Africa. He fought in the Philippines.

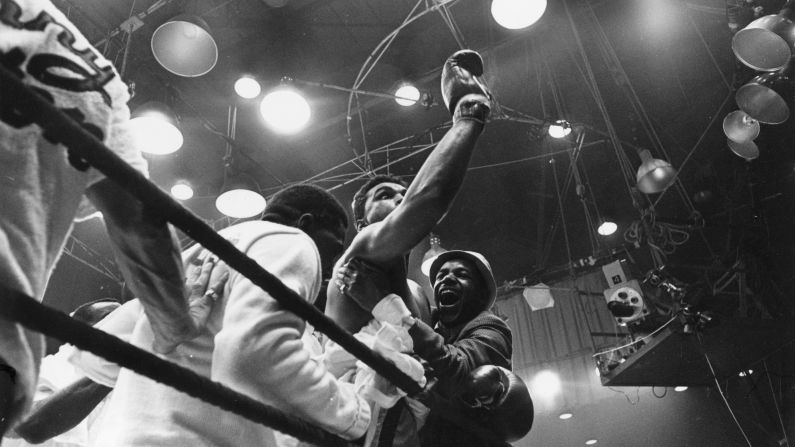

Ali returned to the ring thanks to another African-American son of the South. One of the few black elected officials in the South, Georgia state Sen. Leroy Johnson, negotiated the return of Ali’s license when Nevada, Illinois and New York rejected his request. I was there when he began his glorious comeback. It was an honor and a joy to pray with Ali in the locker room in Atlanta the night of his first fight back.

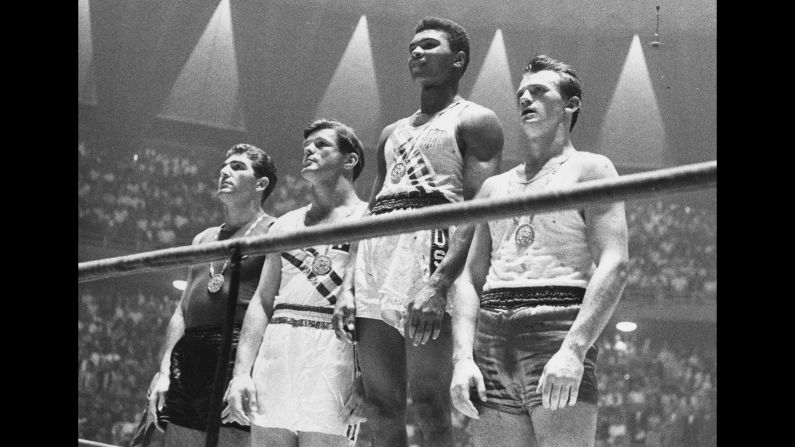

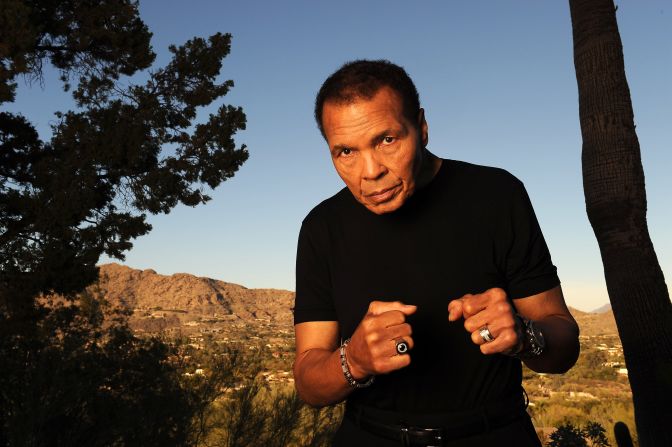

The government tried to destroy Ali. It failed. He went from being reviled to being revered. From being banished from boxing to lighting the Olympic flame in Atlanta. In a singular and significant way he used the highest athletic platform to become a cultural transformer, fighting for justice at home and to end unnecessary wars around the world. His body is gone, but his legacy will live for a long, long time.

Even as Parkinson’s disease slowed his body and slurred his speech, Muhammad never stopped fighting against injustice. A few months ago, the champ issued a statement, condemning Muslim bashing for political gain. “We as Muslims,” the statement said, “have to stand up to those who use Islam to advance their own personal agenda. They have alienated many from learning about Islam. True Muslims know or should know that it goes against our religion to try to force Islam on anybody.”

The world has lost one of the greatest heroes of all time. He sacrificed, the nation benefited. He was a champion in the ring, but, more than that, a hero beyond the ring. When champions win, people carry them off the field on their shoulders. When heroes win, people ride on their shoulders. We ride on Muhammad Ali’s shoulders.

The Rev. Jesse Jackson, a longtime civil rights activist, is the founder and president of the Rainbow/PUSH Coalition. The opinions expressed in this commentary are his.