Sampling Japan’s beef is a priority among many international visitors, with words like Wagyu, Kobe, yakiniku and Matsusaka racing through their minds as they step off the plane.

A word that’s usually excluded from their meat-based vocabularies? Gyutan.

In spite of the rise of nose-to-tail eating in trendy Western culinary circles, beef tongue has yet to set the taste buds of diners aflutter.

Fans of the dish, however, claim that once you get past the psychological resistance to eating tongue, you’ll be hooked for life.

The birthplace of gyutan

Though gyutan is available at yakiniku restaurants all over Japan, Sendai – the largest city in Japan’s northern Tohoku region – is where you’ll find the highest concentration of eateries solely dedicated to grilling up juicy strips of beef tongue.

On my first night in Sendai I headed straight for the original – Aji Tasuke, founded in 1948 by a man named Keishiro Sano.

According to the restaurant, he left his home to apprentice in Tokyo around 1935. It was there that he met a French chef, who he saw cooking up a beef tongue stew. Inspired, he decided to prepare it differently to suit Japanese tastes.

After World War II ended, he returned north and opened a restaurant in Sendai. Due to food shortages, he began serving his take on beef tongue, along with tail soup.

Nearly seven decades on, Sano has passed away but his photo still hangs on the wall and the restaurant is still going strong, now run by his eldest son.

And it’s got competition.

Nowadays you can’t turn a corner in the center of this city of one million people without seeing a restaurant advertising gyutan – “gyu” is Japanese for cow, while the “tan” refers to the English word for tongue.

Tasting the tongues

During my Aji Tasuke visit, staff were helpful but far from effusive.

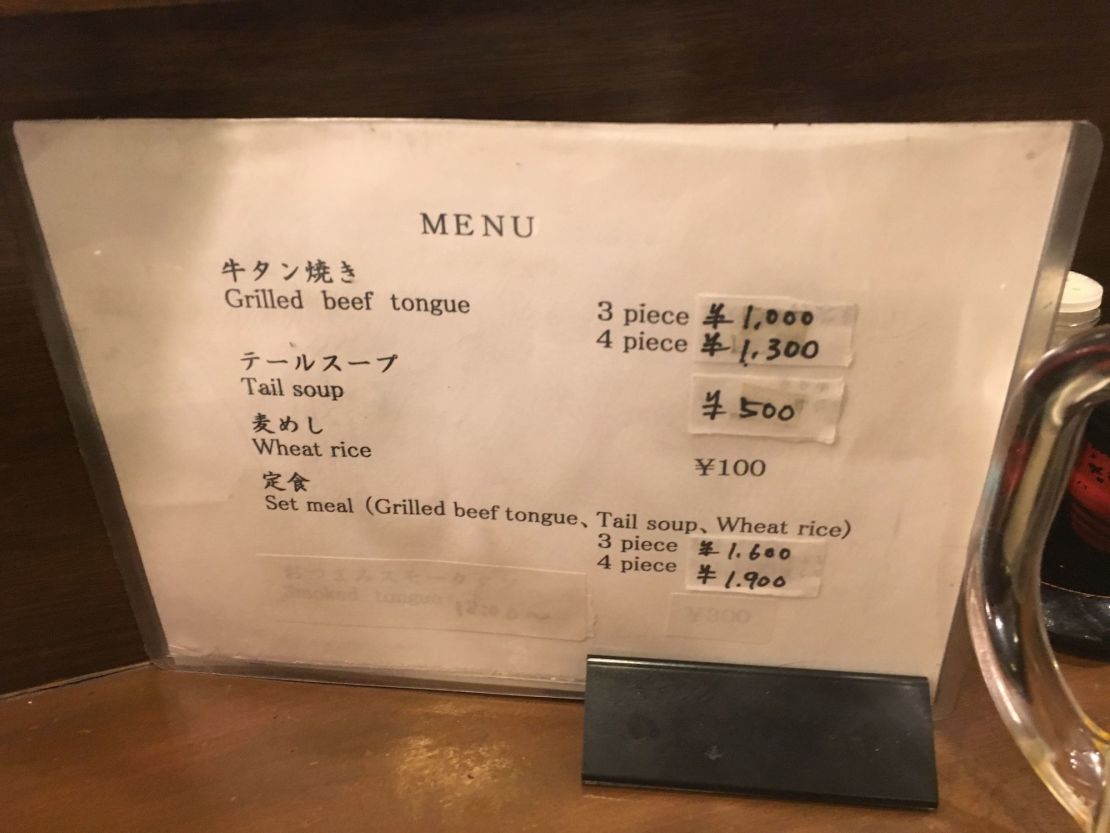

An almost comically short English menu was quickly passed to me as I grabbed one of about a dozen stools at the tiny restaurant’s counter – a front row seat to the action.

One man was on tongue-grilling duty.

He carefully plucked the small, pink cuts of beef tongue from a towering plastic-wrapped slab, laying them atop the flaming charcoal grill.

Using a large pair of wooden chopsticks, he flipped them over twice – about 20 seconds per side. Loud sizzles filled the air as the fat dripped onto the flames.

The juicy tongue slices were perfectly seasoned with just enough salt to allow the flavor of the meat to blast through.

The texture, though a tad bit tougher than regular beef cuts, wasn’t the mastication struggle gyutan virgins might envision.

You can order the beef tongue a la carte, but I recommend the set meal, which includes a bowl of delicious tail soup and a side of mugi gohan (barley rice) for 1,600 yen ($14.66).

For those who want to try other variations of the dish – Aji Tasuke only serves it the one way – restaurants Rikyu and Kisuke have several locations in Sendai.

The beef tongue curry served at both is particularly good.

Made in America

Prized as Japanese beef might be, the tongues served in most Japan restaurants are imported from the United States.

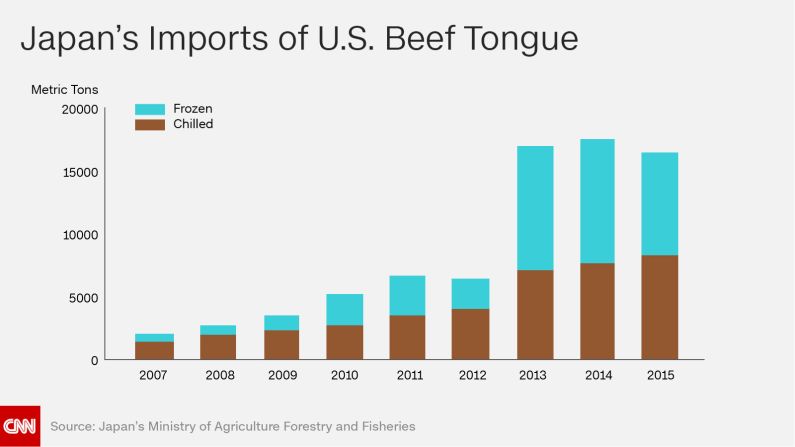

According to Joe Schuele, vice president of communications at the U.S. Meat Export Federation, Japan imported more than 16,500 metric tons of U.S. beef tongue in 2015.

Not all of them are being served in Sendai. Schuele says there are about 22,000 yakiniku restaurants in Japan and nearly all serve beef tongue.

There are two reasons for its popularity.

“U.S. beef tongue has richer flavor than tongues from Australia and New Zealand because U.S. beef is corn-fed,” said Schuele. “U.S. feeding practices also ensure that U.S. tongues have a higher level of tenderness.

“Because it is corn-fed and more tender, U.S. beef tongue also has less cutting loss. Grass-fed tongues require that the muscle surface be removed because that portion tends to be very tough.”

Why Sendai?

To learn more about gyutan’s place in the Japanese diet, I reached out to Japanese food expert Elizabeth Andoh, who has authored several books on the country’s diverse cuisine.

“The Japanese are, in general, all for using food fully,” she said. “It’s a mindset that if you’re going to be slaughtering the beast you should be using everything that’s edible from it.”

This, and a lack of options, could well have contributed to its post-World War II rise.

“I think the whole story of food is all about desperation and imagination,” she said. “And I think that desperation in the form of shortages is certainly part of the story.”

So why is Sendai considered the gyotan capital of Japan, even though the dish is made with U.S. beef tongues?

Andoh points to the country’s regional food identities, a phenomenon in which each prefecture is known for offering its own culinary specialty.

“Most Japanese who stake out that territory don’t step on each other’s toes,” she said.

“It’s sort of an understanding, and it’s not just tongue in Sendai. It’s a way in which Japanese commercialize certain food products.”

This extends to “omiyage” – gifts that Japanese buy for friends, colleagues and family when they travel.

“It’s somewhat obligatory, especially in business, because the assumption is that even if it is for work, you are still making things more challenging for your colleagues in your absence and so inevitably you bring something back,” said Andoh.

For those heading to Sendai on business the obvious omiyage choice is beef tongue, which can be found in frozen, ready-to-travel packages sold by multiple vendors at the Sendai train station.

In Japan, she added, there are even one-day tours that allow travelers to go have lunch to experience a regional specialty.

“There are lots of local companies that will put together tours for Sendai tongue,” added Andoh.

“That being said, tongue is available in Tokyo but typically it’s going to be served in restaurants that advertise it as ‘Sendai style’. It’s something that’s going to bring in customers and assure them that it’s authentic.”

Getting there: Sendai, in Miyagi prefecture, is serviced by regular flights from Japan’s major cities. Shinkansen bullet trains depart from Tokyo multiple times a day. The journey takes less than 2.5 hours.