ISIS on Europe's doorstep

Updated 1309 GMT (2109 HKT) May 26, 2016

Tripoli, Libya (CNN)The call was simple, but it changed what an already dark business meant for one smuggler.

Abu Walid knew his caller to be a devout man, a member of ISIS. And his request was chilling. Could he ship 25 of his people from Libya to Europe on a small boat for $40,000?

Abu Walid -- not his real name -- declined. But it is a request that's becoming increasingly common, he told CNN, in the past two months.

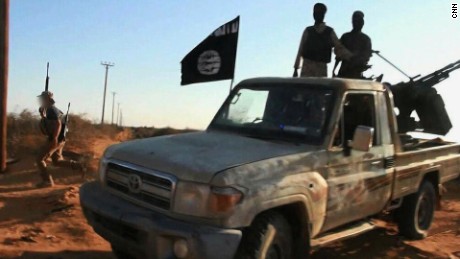

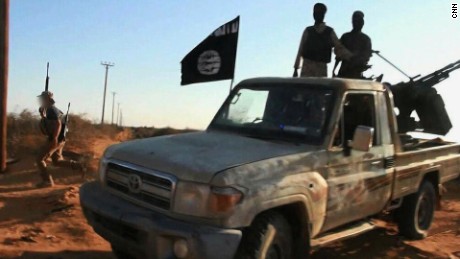

ISIS is trying to infiltrate this trade to get their people to Europe from the chaotic and near-failed state of Libya as the route from Turkey to Greece becomes more heavily policed.

"Exploitation of migrant smuggling networks by ISIS in North Africa has only been a matter of time ... the U.S. and Europe need to act quickly, and together," a Western diplomat told CNN.

Abu Walid's experiences were backed up by two Libyan police officials, who said they had found ISIS militants trying to get to Europe.

He also heard of a recent case of 40 Tunisian ISIS members leaving from the militant stronghold of Sirte. Thwarted by bad weather, they tried again ten days later. He didn't know if they made it.

A senior Libyan military intelligence official in Misrata, Ismail Shukri, said that ISIS militants sought to disguise themselves by traveling with "their families, without weapons, as normal illegal immigrants."

"They will wear American dress and have English language papers so they cause no suspicion."

European officials insist they're trying to be better prepared. A senior EU counter-terrorism official told CNN there were more Europol officers working at potential "hotspots" of entry for migrants.

Still, the prospect of such an influx is a nightmare for Europe.

"If confirmed it is indeed very alarming. It is not one or two trying to move -- it seems more organized," the official told CNN.

Where desperate dreams end

In a dank, dense corridor in Tripoli, among empty plastic bottles and soiled mattresses, is where this new cynical ploy will try to find a place.

This is where we find Eugene, in a group of migrant hopefuls who have just been apprehended by the Libyan police. He's one of many, but every one of the 30 cramped souls here is living its own singular tragedy and horror.

Eugene's dream was desperate, and now it's pretty much come to an end in a tiny house near the seafront, in hostile smuggler territory. Police nervously twitch their weapons as Eugene unravels the story that brought him here.

"I came through desert," he said. "My father is dead, through Boko Haram, through the crisis in Kano [state in Nigeria]. Even my younger brother, he died from the bomb blast last year."

He said he tried to find work as he could not afford the smugglers fees to cross to Europe. "In northern area in Nigeria, most of us we are not safe. Today bomb blast, tomorrow bomb blast, so we are not safe. If you can get anyone to help me ... because I don't know what to do, to tell the truth. Because here in Libya there is no peace."

It's not clear how Eugene's journey ended up in this holding pen, seemingly awaiting a crossing to Europe, but it is on hold for now.

He joins the thousands of African migrants now in detention in Libya -- a number that will grow as the EU's bid to close the Turkish-Greek shoreline intensifies.

The wider the divide, the more difficult to bridge it

Police officials complain to us about the sheer cost of feeding these men. Food, like so many staples, is expensive now: a symptom of Libya's expanding menu of woes.

Libya has for years been wracked by chaos, instability, economic pain and suffering for its people -- all of this drama, after the fall of Moammar Gadhafi, playing out just across from the EU's shores.

It is remarkable how more chaotic it has become in the year since we last visited. Libya now has a third government claiming control -- the Government of National Accord, led by Fayez al-Sarraj and recently installed by the United Nations -- but still struggling to gain a firm hold on the country's institutions. You can't blame them.

Libyans in Tripoli have long been ostensibly governed by the General National Congress. Out east, based in Tobruk, is another government, based around the House of Representatives and dominated to some degree by the military figure of General Khalifa Haftar.

But the longer the split goes on, the more complex its resolution seems. We got a sense of that in the key port city of Misrata.

ISIS had advanced towards the city that day, taking the highway town of Abu Grein. Two suicide bombers, using armored cars to deliver their payload, had caused bloody chaos. The second blast prompted the city to declare a state of emergency.

The main hospital, a staggering hour's drive from the scene of the carnage, accepted a total of 110 injured that night, with nine dead from the second blast. Among the grief and panic, you could hear the confusing yet passionate claim that the faction in the country's east was in league with ISIS and behind the attack. They were short on evidence for the claim, but lacked nothing in conviction.

Western intervention depends on these divides healing, and unity around the third government of Prime Minister-Designate al-Sarraj.

It's true that many Libyans are tired of the power cuts, chaos and dysfunctionality -- and the fact that most banks are surrounded by crowds of angry customers simply hoping they can withdraw their salaries. Sarraj has a chance to instigate change and harness their support, but it may evaporate quickly.

U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry and other world powers' offer to arm Sarraj's government -- if they present a "well sculpted" plan -- is clearly intended to show Libyans that international support rests on them uniting behind one man.

With ISIS controlling a tenth of Libya's coastline, there has seldom been greater urgency. Yet the U.S. military has been in evidence in the country for some time now.

American eyes in the sky -- and on the ground

Carved in the rock of the remote Sicilian Island of Pantelleria is an aircraft hangar, apparently built for World War II, yet now central to the latest extension of what was the war on terror. From it flies a specially adapted twin propeller plane, its underbelly extended to presumably house surveillance equipment.

Italian government documents and public aviation records show it is run by the U.S. government to conduct reconnaissance missions over Northern Africa, especially Libya.

Locals on Pantelleria are friendly to their American guests and almost grateful for their presence, given how close across the sea ISIS are. But the flights, in place since late 2014, are a sign of how the United States has been slowly gathering information and trying to build alliances against ISIS's foothold here.

Down on the road towards Sirte on the Libyan coast, we encountered evidence of how U.S. troops were palpably on the ground as well. Libyans we met on the long, isolated highway reported seeing four SUVs containing Western-looking troops.

A Libyan official told us that about a dozen American Special Forces were working out of a nearby military base. The Pentagon confirmed they were "meeting with a variety of Libyans," but didn't supply details.

They have a difficult task on the road between Misrata and Sirte. For a start, ISIS are ruthlessly capable of pushing back the Libyan defensive lines with the huge suicide bombs we saw that day.

Secondly, the Misrata militia defending the road are not loyal to the Western-backed Sarraj government, but instead the Tripoli-based GNC government. The Pentagon has since confirmed other teams are meeting Libyans in the east and in Tripoli too. But is this too little too late?

It is staggering, after the West's slow response to ISIS in Syria and Iraq -- and the now years-long disaster that beckoned -- to observe such a slow reaction to ISIS's expansion in Libya. Its vast coastline is not only mere hours by boat away from Europe's soft southern underbelly, but home as well to oil refineries Italy and other EU countries depend upon.

In the year between our visits, Libya has sunk much further towards the abyss, and ISIS have expanded. There is no easy Western intervention, but there is also no equally simple rationale for sitting back and letting the collapse speed towards us, as the West seems currently content to do.