Story highlights

Mori was only eight years old when two atomic bombs were dropped on Japan

He spent years tracing the American POWs who died to add their names to the Hiroshima memorial

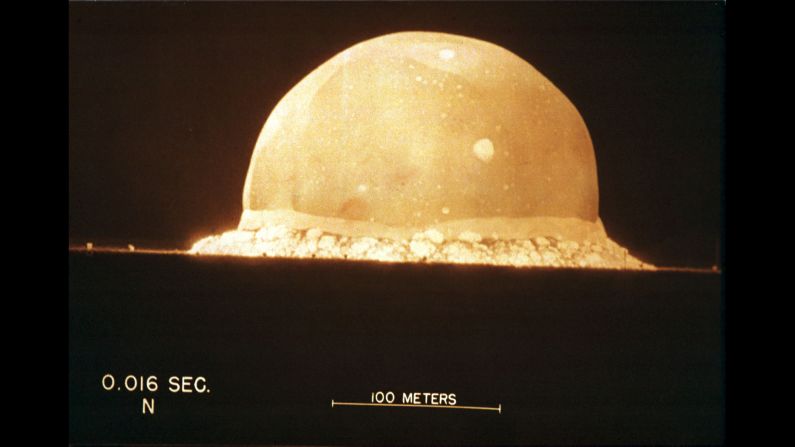

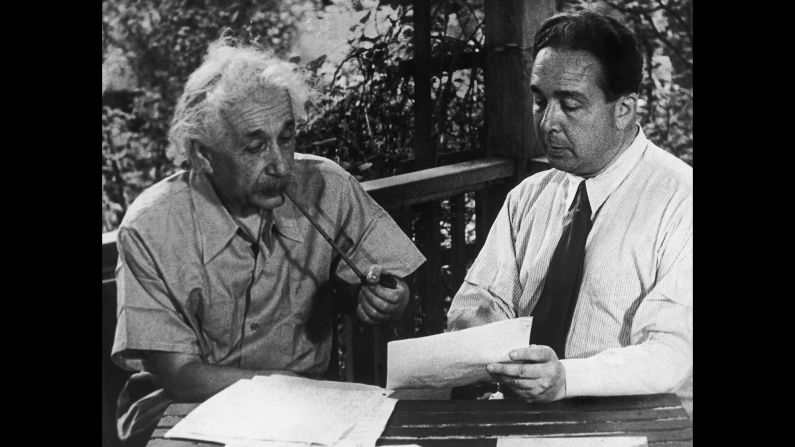

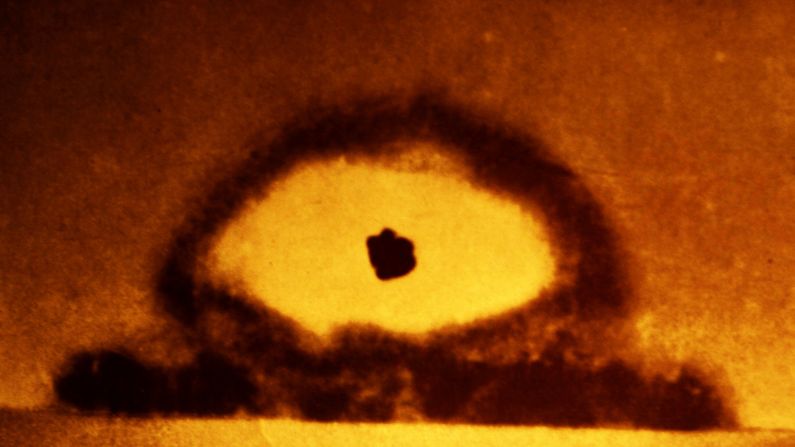

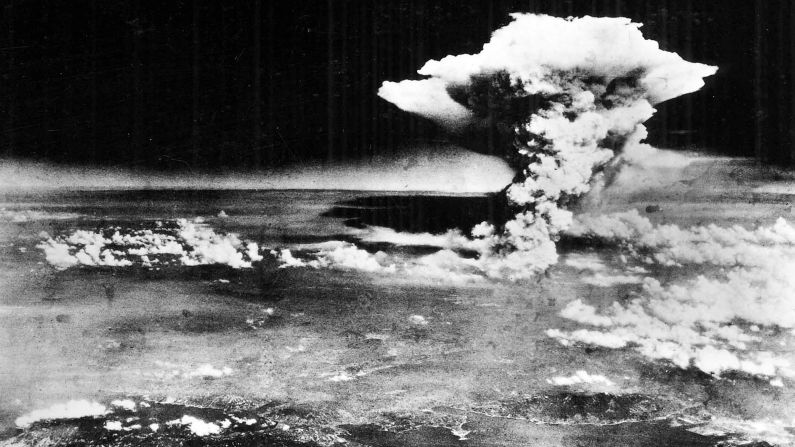

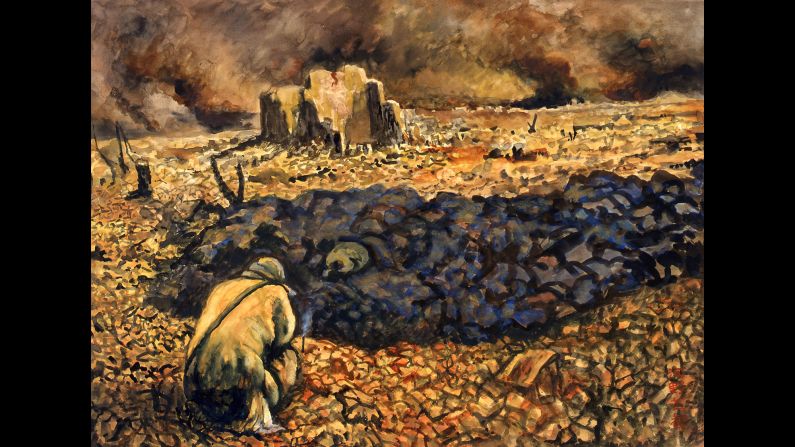

Editor’s Note: The atomic bomb attacks on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had, by the end of 1945, taken well over 200,000 lives. Many of those not instantly vaporized by the fireballs were left with horrific injuries. More would die from the effects of radiation or endure lifelong health complications. When CNN’s Will Ripley moved to Japan in 2014, he expected to encounter anger over America’s wartime actions. Then he met 79-year-old Hiroshima survivor Shigeaki Mori.

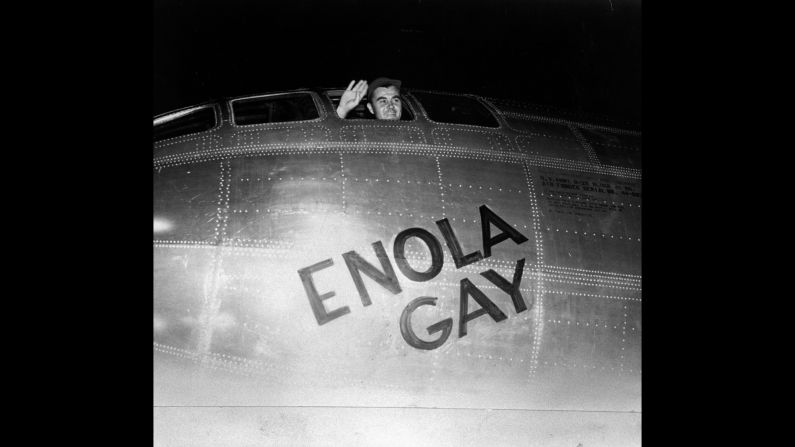

Shigeaki Mori was eight years old on August 6, 1945. He was walking to school at 8:15 a.m. when an American B-29 bomber, the Enola Gay, dropped the A-bomb nicknamed “Little Boy” on Hiroshima.

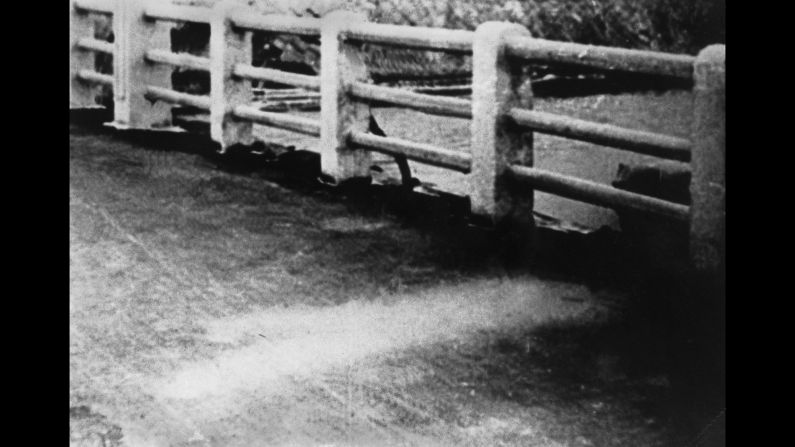

“I remember the blast suddenly hit me from above. I was blown off the bridge and fell into the river. Because the river was shallow…and the waterweeds growing thick, I survived without injuries and burns,” Mori says.

The A-bomb survivor helping to mend Hiroshima wounds

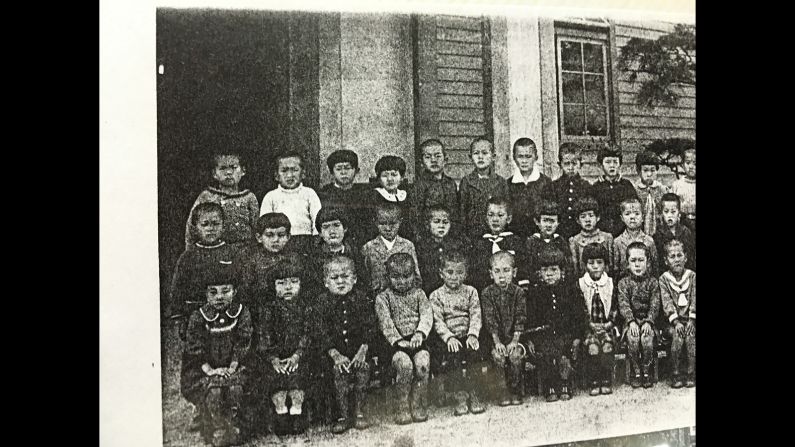

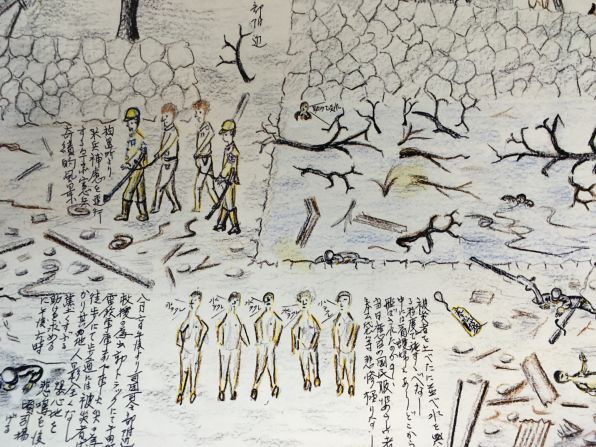

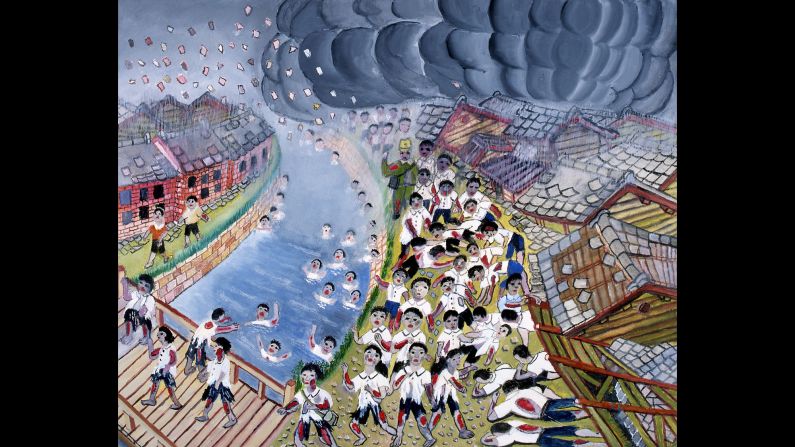

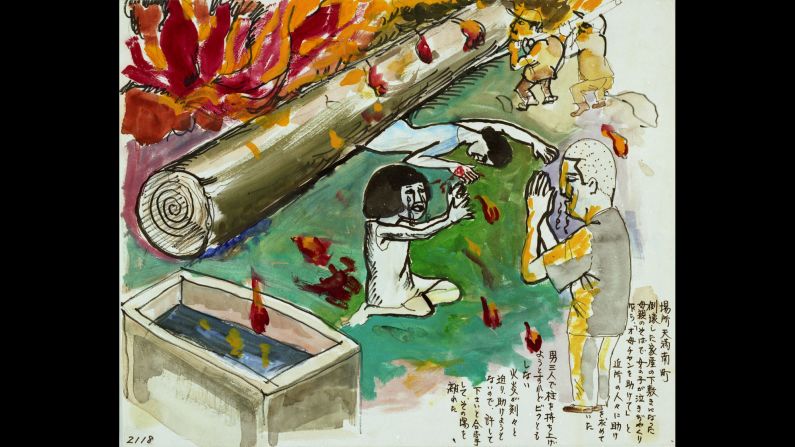

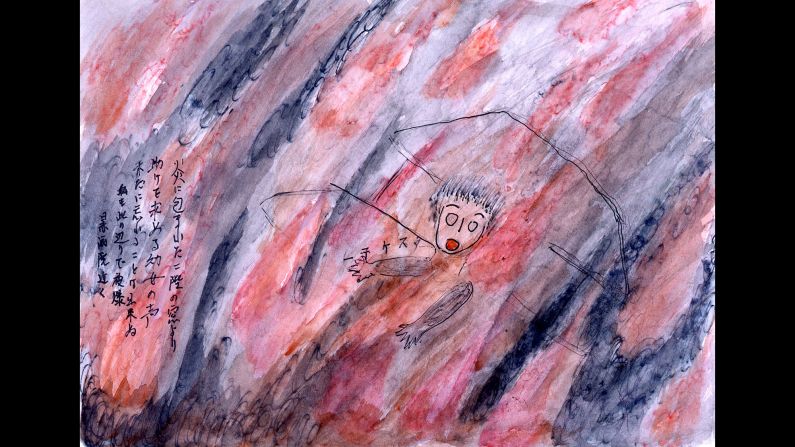

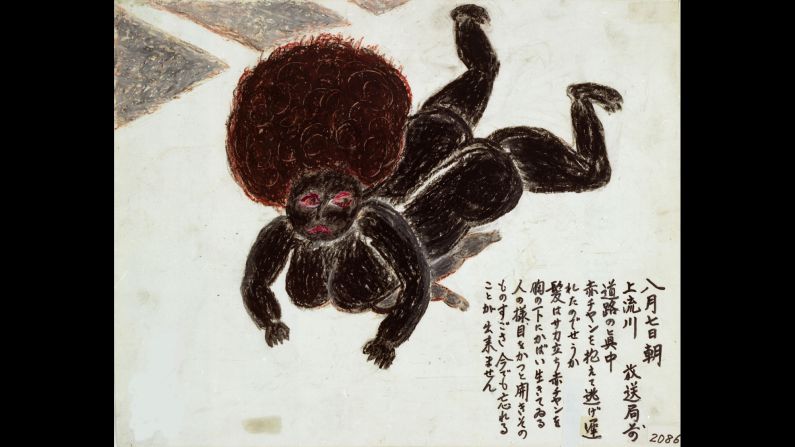

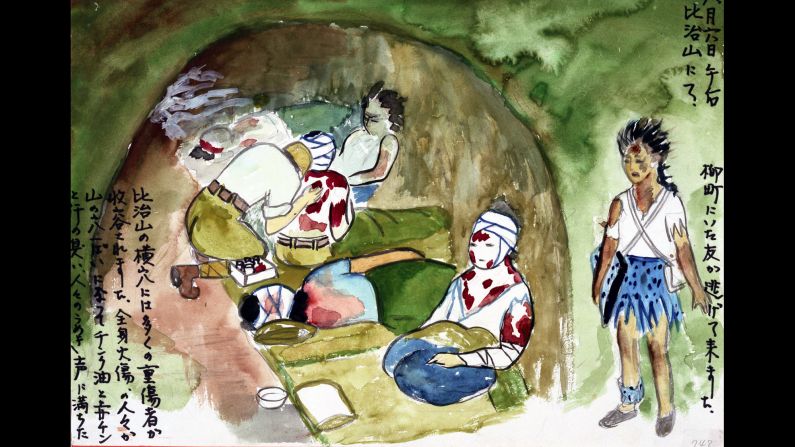

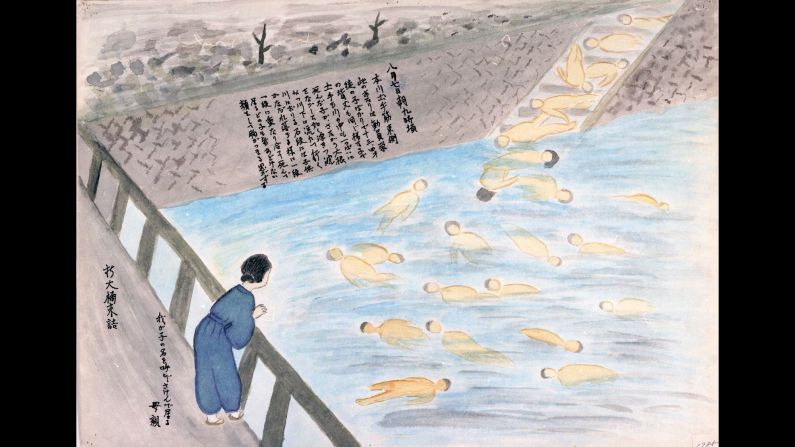

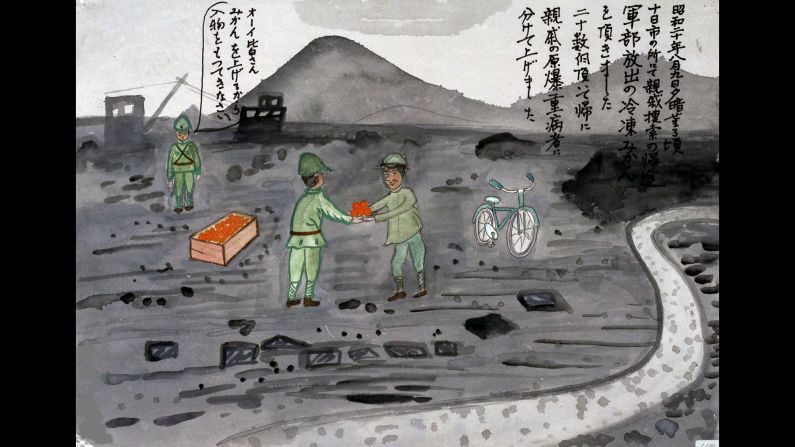

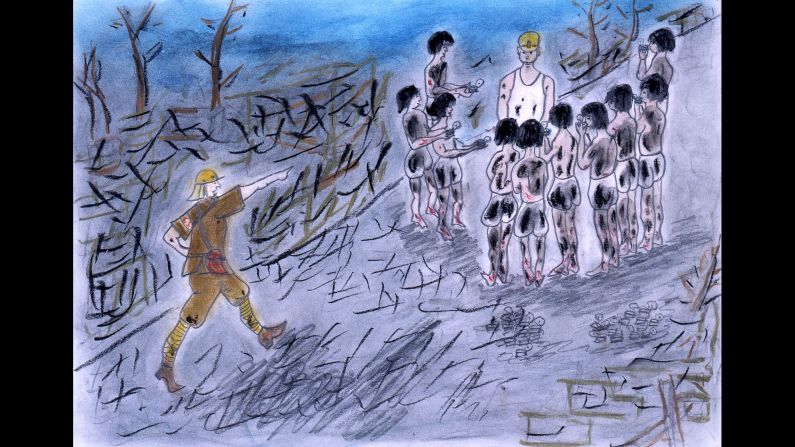

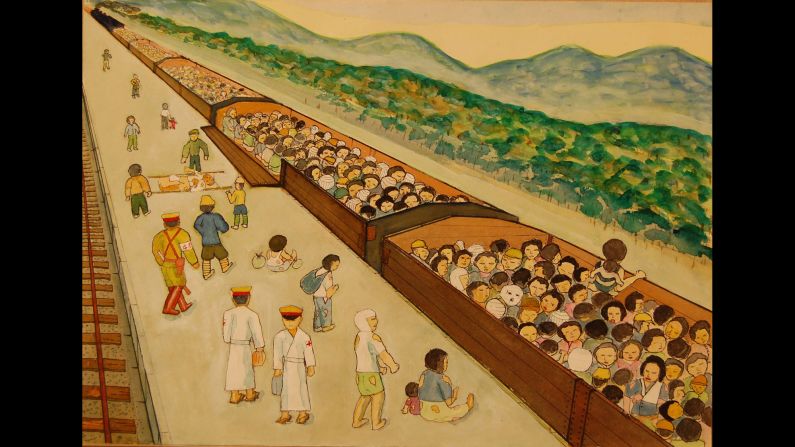

Mori’s old primary school was 400 meters from ground zero. He says all the teachers and students in the building died. A police headquarters holding a small group of American POWs sat next to the school. Mori says he saw the captured airmen from his schoolyard. Some Hiroshima survivors even drew sketches of them.

What Hiroshima taught the world

Lost American lives

Today, we know 12 American POWs died as a result of the A-bomb in Hiroshima. The POWs included the crews of two downed American bombers – the Lonesome Lady and the Taloa.

The youngest, Airman 3rd Class Norman Roland Brissette of Lowell, Massachusetts, was just 19. But due to extreme secrecy and political sensitivity, it wasn’t until the 1970s that de-classified U.S. documents verified the presence of American POWs there. And even then, surviving families knew very little of the circumstances surrounding their relatives’ captivity and deaths.

The first use of the atomic bomb

Mori, a local historian, felt even Japan’s former enemies deserved closure. He was determined to uncover details of the POWs situation, share the information with their families, and ensure that the American names were placed on the wall of the Hall of Remembrance in Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, alongside the tens of thousands of other victims.

We can still achieve a world without nuclear weapons

Decades of searching

Long before internet searches and easy access to information, Mori had only a list of twelve POW names a local professor gave him. He borrowed American phone books from the library.

For more than 20 years, he spent weekends going down the list of names and making calls from his home in the hills overlooking downtown Hiroshima. For some with common surnames, it would take several years to find their families.

“My phone bills were huge. My wife was upset about it,” Mori says.

Mori speaks only a few words of English, so he relied on operators to ask the relatives if anyone in their families died in the A-bomb.

Drawings show haunting memories of Hiroshima

“At the beginning, they didn’t understand why I was doing this and they wondered how I reached them. They were very skeptical and it took a while to gain their trust,” Mori says.

The American families were skeptical that Mori wasn’t asking for money to undertake the tedious process of helping them complete the Japanese language paperwork to have the American POW names and photos added to the Hiroshima memorial. It took decades of phone calls and letters to complete the process. Mori gave the POW’s families previously unreleased details of their captivity, and offered to register their names on the official list of victims.

Opinion: When Hiroshima speaks, President must listen

70th anniversary of the bombing

Despite decades-long friendships forged with those American families, Mori says he never expected what is scheduled to happen on Friday, when President Obama is set to become to the first U.S. president to visit the site of the first atomic bomb attack.

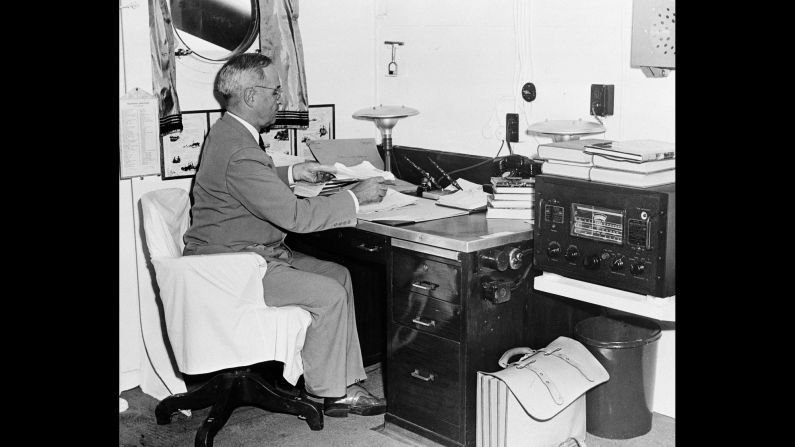

Officials said Obama won’t apologize for Truman’s decision, but he will offer reflections on the devastating toll of war on innocent civilians.

“Never in my lifetime did I think an American president would visit Hiroshima. I think it is wonderful that he will visit Hiroshima to mourn for all victims of war,” Mori says.

As I sit next to Mori in his modest living room, walls lined with historical books much like my father’s own library, I tell him it is remarkable what he has accomplished. Not only was he able to locate these families without relying on Google, but he also overcame the hatred he must have felt towards the U.S. – the country that dropped an A-bomb on his city – killing members of his family, his friends and neighbors.

“Thank you very much,” he says tearfully in English. “Don’t mention it.”