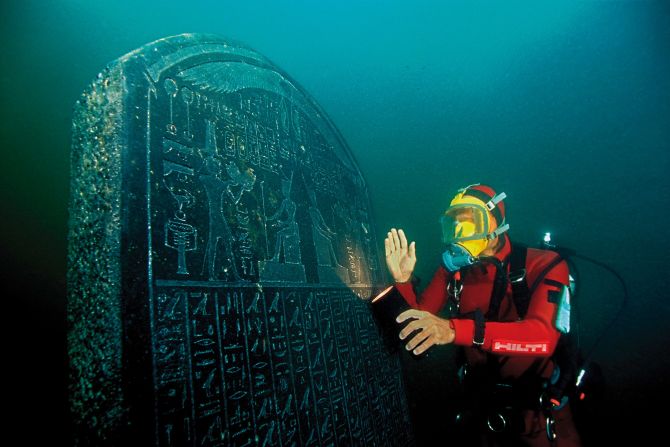

Until 1996, two of Egypt’s greatest cities were missing. Then along came French archeologist Franck Goddio, who made an extraordinary discovery underwater.

For 1,000 years, Thonis-Heracleion was completely submerged. Fish made their homes among the rubble of mighty temples; hieroglyphs gathered algae. Gods and kings sat in stasis, powerless, their statues slowly withdrawing from the world, one inch of sand at a time. Goddio spent years surveying this find, as well as neighboring Canopus, which was rediscovered by a British RAF pilot in 1933 who noticed ruins leading into the waters.

Thanks to a new exhibition at the British Museum, Goddio’s incredible finds will soon be open to the public.

Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds opens May 19, and according to museum curator, Aurelia Masson-Berghoff, the exhibition pulls back the curtain on what was once one of archeology’s greatest mysteries.

“(Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus) were known from Greek mythology, Greek historians and Egyptian decrees, and now we know where they were.”

Why did they sink?

Likely founded in the 7th century BC, Thonis-Heracleion and Canopus acted as major trade hubs between ancient Egypt, Greece and the wider Mediterranean, located as they were at a handy intersection. But circumstances ultimately conspired against them, explains Masson-Berghoff.

“Several natural phenomenon caused these cities to sink by a maximum of (32 feet) below the sea,” she says, noting that a naturally rising sea level, subsidence and earthquakes (which ultimately triggered tidal waves) all played a hand.

Gods of yester-millennium

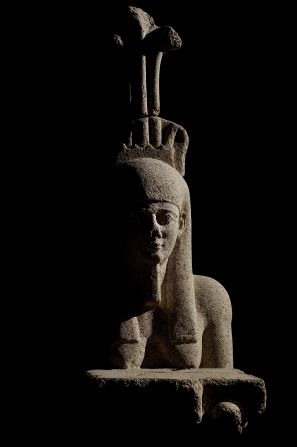

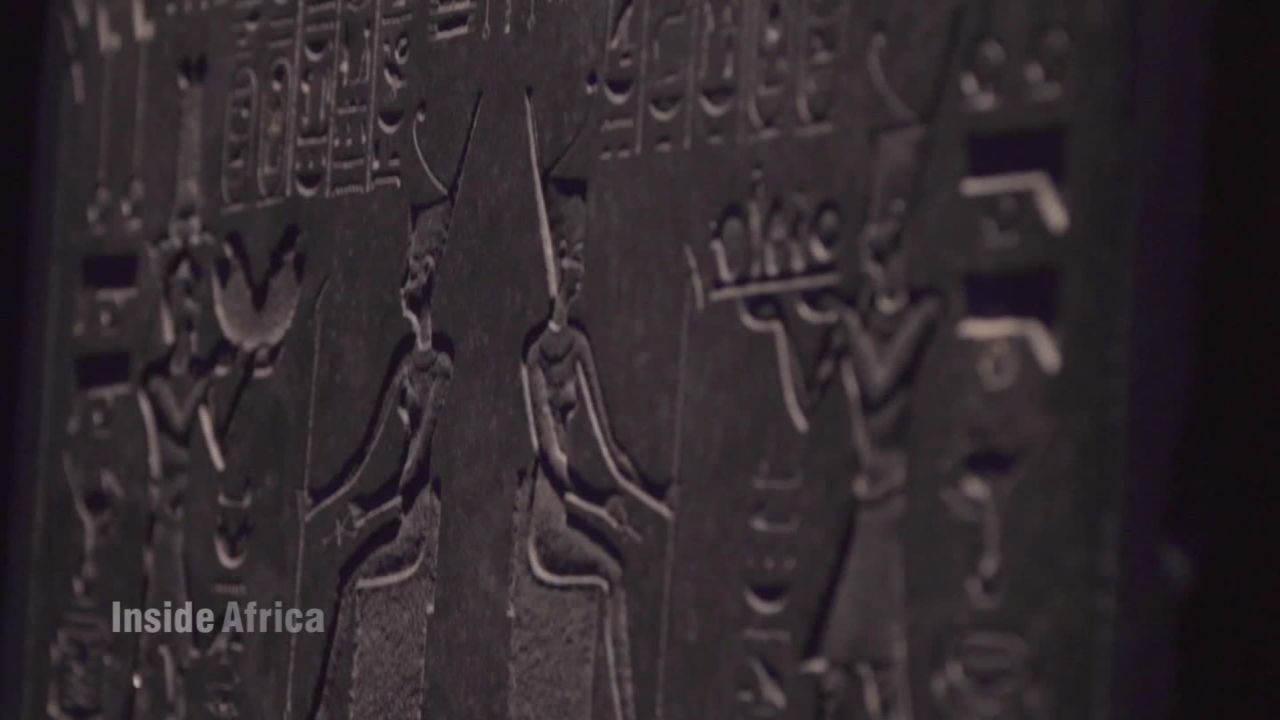

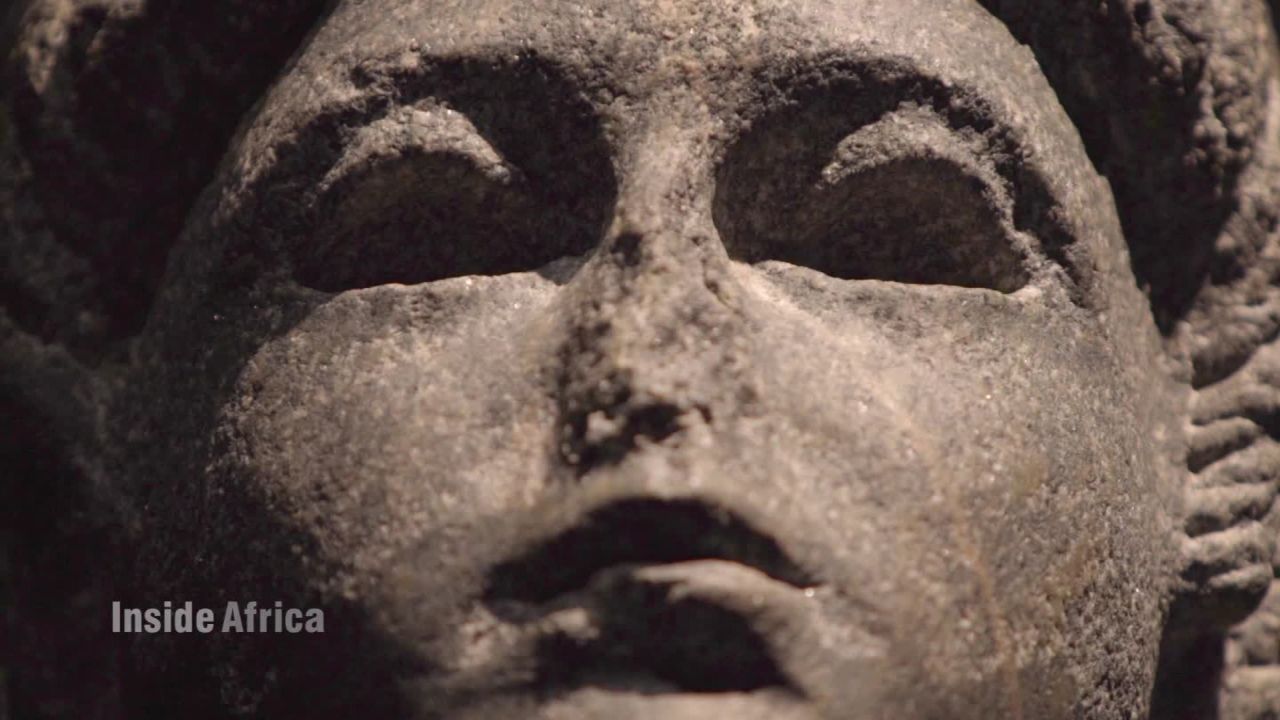

Masson-Berghoff explains they also learned a lot from the form taken by the religious statues dug up from their watery grave. The statues were mainly of Ptolemaic gods with human features that represented the same qualities Egyptians prescribed to animals

“The Greeks were not exactly into animal-shaped gods nor into animal worship,” she explains. “The Ptolemies, the Greco-Macedonian rulers of Egypt after Alexander the Great, created a human-shaped version of a very old Egyptian god, the sacred bull Osiris-Apis. In its ‘Greek’ form, he became Serapis, combining the aspects and functions of major Greek gods.”

One of the statues was that of a colossal head representing the god Serapis, a Greek human-shaped version of the Egyptian god Osiris-Apis.

“We will show in ‘Sunken Cities’ a variety of sculptures depicting these Greco-Macedonian rulers as Egyptian Pharaohs, wearing Egyptian crowns and acting as if they were Egyptian Pharaohs,” the curator says.

It was not vanity that prompted their change in style, but shrewd political maneuvering. “The Ptolemies really understood that they needed the support of the local priesthood and population, to legitimize their rule,” Masson-Berghoff argues. “To achieve this, they adopted Egyptian beliefs, rituals and iconography.”

The largest item on display is a statue of Hapy, ironically the god of flooding. Over 16-feet tall and weighing 12,000 pounds, the pink granite sculpture dates from the fourth century BC, long before Thonis-Heracleion disappeared into the sea.

Also worth noting is what Goddio’s team left on the seabed. The archeologist discovered 69 ships: “the largest assemblage of boats ever discovered,” Masson-Berghoff claims – one of them likely used on a Grand Canal which linked Canopus and Thonis-Heracleion, upon which a sacred barge made of sycamore would travel during the Mysteries of Osiris, a celebration of the god of the underworld.

All of this, however, is just a drop in the bucket.

“What you need to know is that Franck excavated less than 5% of this site,” the curator stresses. “They left a lot of material on the seabed.”

The BP exhibition Sunken Cities: Egypt’s Lost Worlds runs at the British Museum, London from May 19 to November 27.