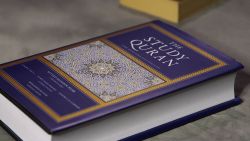

On a warm November night in Washington, a small group of American Muslims gathered at Georgetown University to celebrate “The Study Quran,” new English translation of Islam’s most sacred scripture.

By the next evening, several said, the need for the book had become painfully apparent.

The Islamic State had struck again, this time slaughtering 130 men and women in Paris. The group quoted the Quran twice in its celebratory statement.

On Friday, investigators told CNN that ISIS also may have inspired this week’s massacre in San Bernardino, as one of the suspects allegedly pledged allegiance to the group in a Facebook post.

After the Paris attacks, President Barack Obama renewed his call for Muslim scholars and clerics to “push back” against “twisted interpretations of Islam.” The battle against ISIS and other extremists will take more than military might, he said. It is an ideological war as well.

Thus far, however, many English translations of the Quran have been ill-suited to foiling extremist ideology or introducing Americans to Islam. Even after 9/11, when interest surged and publishers rushed Qurans to the market, few of the 25 or so available in English are furnished with helpful footnotes or accessible prose.

Meanwhile, Christians or Jews may pick up a Quran and find their worst fears confirmed.

“I never advise a non-Muslim who wants to find out more about Islam to blindly grab the nearest copy of an English-language Quran they can find,” Mehdi Hasan, a journalist for Al Jazeera, said during the panel discussion at Georgetown.

Ten years in the making, “The Study Quran” is more than a rebuttal to terrorists, said Seyyed Hossein Nasr, an Iranian-born intellectual and the book’s editor-in-chief. His aim was to produce an accurate, unbiased translation understandable to English-speaking Muslims, scholars and general readers.

The editors paid particular attention to passages that seem to condone bloodshed, explaining in extensive commentaries the context in which certain verses were revealed and written.

“The commentaries don’t try to delete or hide the verses that refer to violence. We have to be faithful to the text, ” said Nasr, a longtime professor at George Washington University. “But they can explain that war and violence were always understood as a painful part of the human condition.”

The scholar hopes his approach can convince readers that no part of the Quran sanctions the brutal acts of ISIS.

“The best way to counter extremism in modern Islam,” he said, “is a revival of classical Islam.”

Translation wins plaudits from academics

At the Georgetown panel, after a musician played a Persian lute, Nasr introduced his hand-picked translation team as “his children.” All are his former students and Muslims, the scholar said, a condition he set before signing the contract with the publisher, HarperOne.

The book has been endorsed by an A-list of Muslim-American academics. One, Sheikh Hamza Yusuf, called it “perhaps the most important work done on the Islamic faith in the English language to date.”

Retailing at $60, “The Study Quran” may be pricey for many readers, particularly the young Muslims its editors and publishers are keen to reach. But Mark Tauber, HarperOne’s senior vice president, said presales were strong enough that HarperOne recently printed 13,000 more copies in addition to the first run of 10,000.

“I don’t know if we’ve ever reprinted a resource like this before it’s gone on sale,” Tauber said.

The book was also expensive to produce, requiring outside funding from philanthropists such as King Abdullah II of Jordan and the El-Hibri Foundation, which promotes religious tolerance. The donations paid the salaries of three translators while they took sabbaticals from university jobs to spend six years digging into centuries of commentary on the Quran, Nasr said.

On many pages of “The Study Quran,” that commentary takes up more space than the verses, making the book resemble a Muslim version of the Jewish Talmud.

And for the first time in Islamic history, said Nasr, this Quran includes commentary from both Shiite and Sunni scholars, a small but significant step at a time when the two Muslim sects are warring in the Middle East.

“We hope this will be a small contribution to unity in the Islamic world.”

Quran is difficult to translate

In the aftermath of the Paris murders – just as copies of “The Study Quran” were en route to bookstores, colleges and homes – one U.S. presidential candidate said the government should register Muslims and monitor mosques. Others said the United States should bar Syrian Muslim refugees.

The message is clear: Muslims are different; they can’t be trusted. Increasingly, many Americans agree. According to a poll released by the Public Religion Research Institute this month, 56% said Islamic and American values are not compatible.

Understanding Islam, to a degree, means comprehending the Quran, which Muslims believe was revealed orally to the Prophet Mohammed 1,400 years ago. But the book, which was originally written in Arabic, can be hard to grasp and is notoriously difficult to translate, with many words conveying multiple layers of meaning.

The Quran itself says that some verses are clear, while others are allegorical, the ultimate interpretation known only to the Almighty. Likewise, some passages are poetic, describing the grandeur of God and pleasures of paradise. Others detail how Mohammed captured territory and defended his new community, at times with force.

Those verses should be read literally and applied liberally, ISIS and other extremists argue. The editors of “The Study Quran” disagree.

Questions about literal interpretation

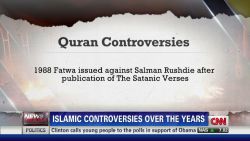

ISIS presents itself as a return to the roots of the religion, back to a time when the Quran was the only guide for Mohammed and his companions – no commentary, no debates. But its brand of Islam, known as Wahhabism, emerged in the 18th century. It is a relative latecomer to the tradition and has always been a minority view among Muslims, scholars say.

By contrast, early Muslims revered the Quran as the literal word of God but knew that not every verse should be interpreted literally. So disputes and commentary about sacred scripture are not a modern, liberal betrayal of Islamic tradition. They are the tradition.

Still, those who argue that “Islam is a religion of peace” are wrong if they mean the faith is pacifist, said Caner Dagli, one of the editors and a scholar at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts. “The Quran does allow the justified use of force.”

Mohammed wasn’t just God’s messenger, Muslims believe. He was also a head of state who built a new community in hostile territory, which often meant seizing and holding land through force.

The Bible has also its share of bloody moments. But many of those moments are part of a larger story – Joshua overcoming the Amalekites, for example. It’s apparent that the battle occurred at a particular historical moment and is not meant to be repeated.

But in the Quran, many of the stories are stripped away, making the commentary – which provides the context – even more crucial.

“A lot of the classical commentaries viewed these verses (on violence) as having limited application, and that’s what we wanted to bring out,” said Joseph Lumbard, one the translators of “The Study Quran.”

Selective use by ISIS

Take, for example, verse 47:4, a text that ISIS has used to justify its brutal beheadings of its captives in Iraq and Syria. It reads:

“When you meet those who disbelieve, strike at their necks; then, when you have overwhelmed them, tighten the bonds. Then free them graciously or hold them for ransom, till war lays down its burdens. …”

Taken alone, the first sentence could be read as condoning the killing of non-Muslims wherever ISIS encounters them, whether it be an Iraqi desert or Parisian cafe.

But the context makes clear that the verse is “confined to the battle and not a continuous command,” Lumbard said, noting that the verse also suggests prisoners of war can be set free, which ISIS apparently ignores.

In the Qurans pushed by the Saudis and ISIS, questions can arise even in peaceful-seeming verses.

After praising God, the Quran’s first surah (chapter) rebukes sinners who anger the Almighty or wander from the faith. In the Saudi-promoted translation, the guilty parties are named in parentheses: Jews and Christians.

The translation an Islamic State recruiter reportedly sent to a young American is even harsher.

In the online version, a footnote asserts that Mohammed himself said: “Those upon whom wrath is brought down are the Jews and those who went astray are the Christians.”

The Jews “rejected Jesus, a prophet of God, as a liar,” the footnote continues, while Christians erred by believing that Jesus is divine.

Lumbard pushes back against that interpretation, arguing that elsewhere in the Quran it is evident that anyone, including Muslims, can irk God and wander from the straight and narrow. And the saying – or hadith – attributing Christian and Jewish insults to Mohammed is of debatable authenticity, the scholar says.

There were times, though, when even Mohammed disliked the Quran’s message. Verse 4:34 is one of those instances, said Maria Dakake, an expert on Islamic studies at George Mason University in Virginia.

One of the most controversial sections of the Quran, 4:34 is sometimes derisively called the “beat your wife” verse. It says that if men “fear discord and animosity” from their wives, they may strike them after first trying to admonish their spouse and “leave them in bed.”

“It’s obviously a difficult verse,” said Dakake, the only woman on the translation team of “The Study Quran.”

“I found it difficult when I first read it as a woman, and when people today, both men and women, try to address the meaning of the verse in a contemporary context, they can find it difficult to understand and reconcile with their own sense of right and wrong.”

But Dakake said that while reading through the reams of commentary, she found that Mohammed did not like the verse, either. In one hadith, or saying attributed the prophet, he reportedly said, “I wanted one thing, and God wanted another.”

“That was very meaningful to me,” Dekake said. “We can say, looking at this commentary, that hitting your wife, even if it is permitted in the Quran, was not the morally virtuous thing to do from the point of view of the prophet.”

Opinion: No, ISIS doesn’t represent Islam

A window to encountering one’s soul

It’s sometimes hard for outsiders to grasp how complex Islamic tradition is. There is no central authority, such as the Pope, to hand out edicts or excommunicate heretics. Islam is more akin to Judaism than Christianity. Schools of interpretation revolve around charismatic scholars.

Many Islamic institutions have faltered, though, opening the door for fundamentalists and making it easier for ISIS to peddle its view of the Quran. It preys on the religiously ignorant and keeps recruits isolated from mainstream Muslims.

Still, few extremists pick up a holy book one day and a suicide vest the next. The road from religious believer to radical is dark and winding. Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, said radicalization is often caused by a “perfect storm” of political, social, economic and religious grievances.

So Hamid said he is somewhat skeptical about what if any effect the “The Study Quran” could have on counterterrorism.

“I don’t think we should expect major changes because of some commentary and footnotes on the bottom of the page. If it results in a more nuanced, contextual interpretation of the Quran, that’s great. But it’s hard to make the jump from there” to winning a war of ideas with ISIS.

In any case, “The Study Quran” may not be universally accepted by American Muslims. Nasr is known for his work on Sufism, an esoteric branch of Islam that stresses the inner life of adherents. Already, Lumbard said, there has been some criticism of the translation by Muslims who call it “too Sufi.” That is, too philosophical and open to myriad traditions.

At the Georgetown celebration, Imam Suhaib Webb, a popular American cleric, said the book was designed not to counter violent extremism but to help Muslims encounter their souls.

In a phone interview the day after the Paris attacks, Webb sounded exasperated that ISIS is tarnishing Islam and twisting the tradition’s teachings, he said, to meet its violent ends.

A reporter asked: How could “The Study Quran” help?

Webb said he imagines a young Muslim man – the kind of lost soul who grasps for the nearest certainty he can find. He imagines that young man watching ISIS or al Qaeda propaganda online, alone in his room, listening to them quote the Quran, trying to coax him into violent action.

And then Webb imagines the young man opening “The Study Quran,” and reading scholars’ commentaries on those perplexing verses, and finding that most of them, perhaps all of them, disagree with the terrorists.