Story highlights

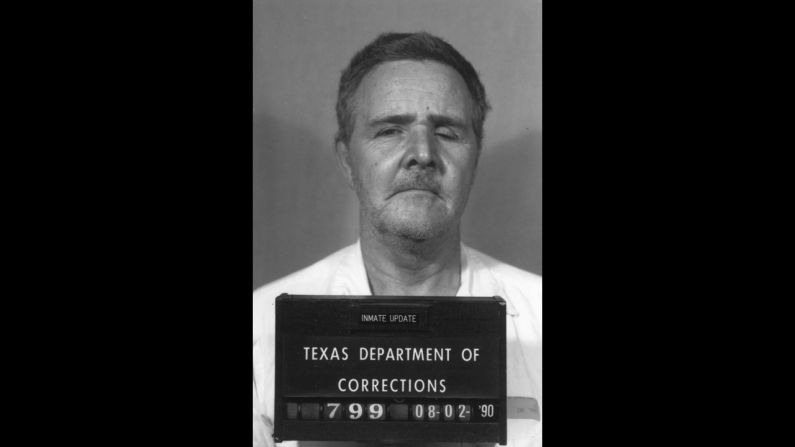

Serial killer John Wayne Gacy was arrested in December 1978

That's around the time Andy Drath, then 16, was last seen in Chicago heading for California

Investigators probing Gacy's victims tied Drath to a 1979 homicide in San Francisco

Because of John Wayne Gacy, John Doe No. 89 now has a name.

It’s Andy Drath, who as a teenage boy fit the profile of many of the serial killer’s victims. Authorities don’t think Drath was one of them, though investigators looking into Gacy’s past did manage to put two and two together in a major breakthrough in a 36-year-old cold case and major relief to Drath’s family.

Cold case cops find new DNA strategy

“You should never lose hope in finding your loved one.” said Dr. Willia Wertheimer, Drath’s half-sister who submitted DNA that proved pivotal. “… John Doe No. 89 now will come home to his kid sister with his own name – Andy.”

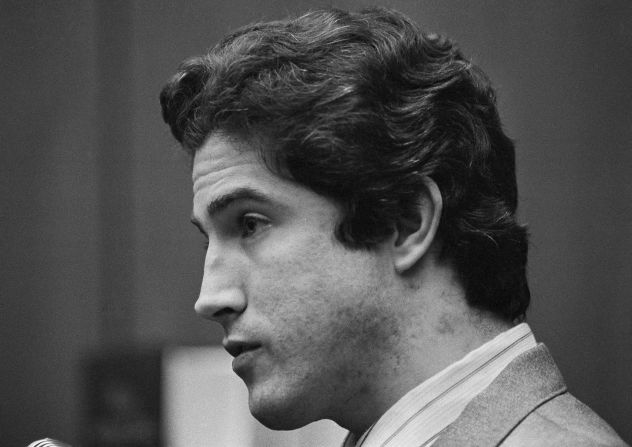

A ward of Illinois’ Department of Children and Family Services, Drath was a 16-year-old boy when he was last seen in late 1978 or early the next year, the Cook County, Illinois, Sheriff’s Office announced Wednesday. He’d gone west to San Francisco, hoping to have his guardianship transferred there.

Authorities launch new effort to identify Gacy victims

It was in that Northern California city, in June 1979, that police found a male’s body with multiple gunshot wounds in a homicide.

They didn’t know who he was, much less who killed him. And, according to authorities, his case went cold.

At least until Gacy entered the picture.

Gacy investigators sought help

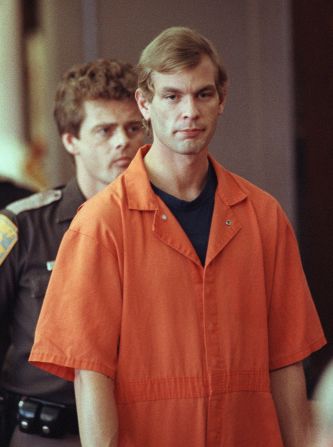

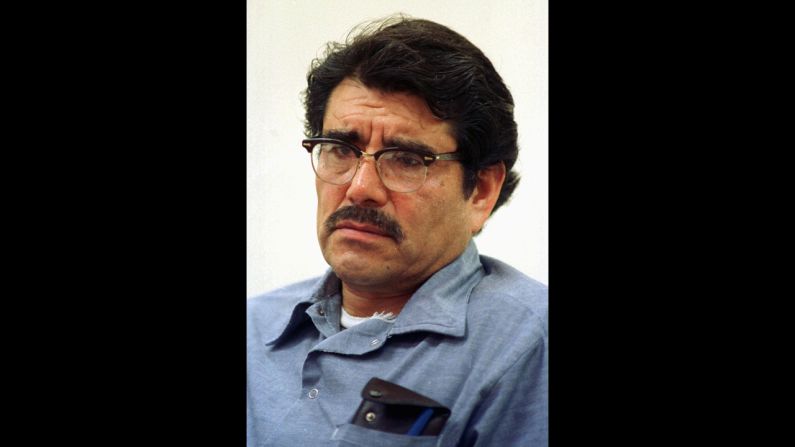

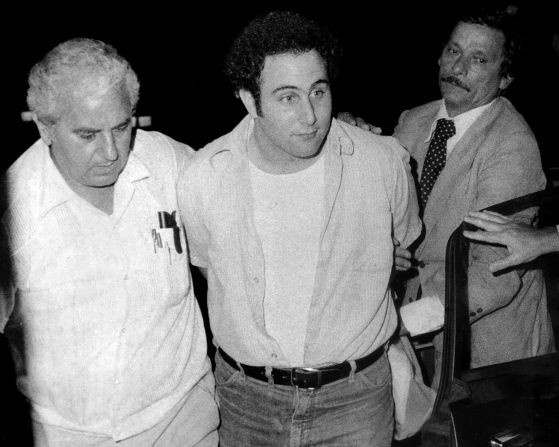

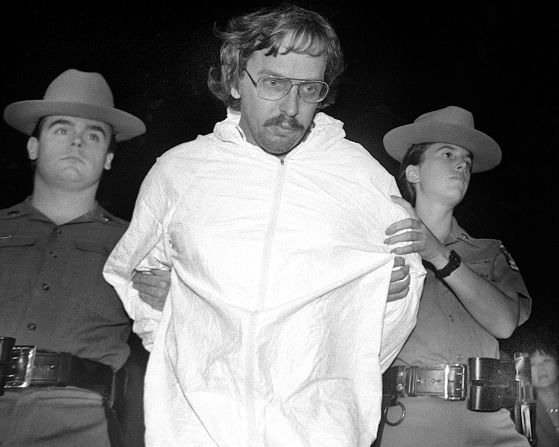

Gacy was arrested in December 1978, and about 14 months later, he went on trial. It ended with his conviction for raping and killing 33 boys and young men who he had lured into his home over a span of six years. To get them there, he’d promised them construction jobs, drugs and alcohol or by posing as a police officer or by offering money for sex.

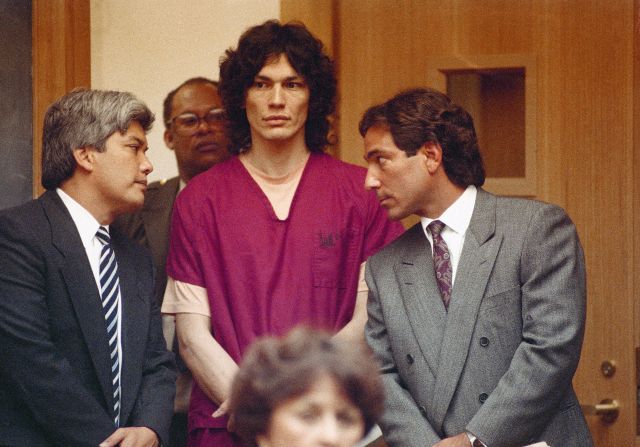

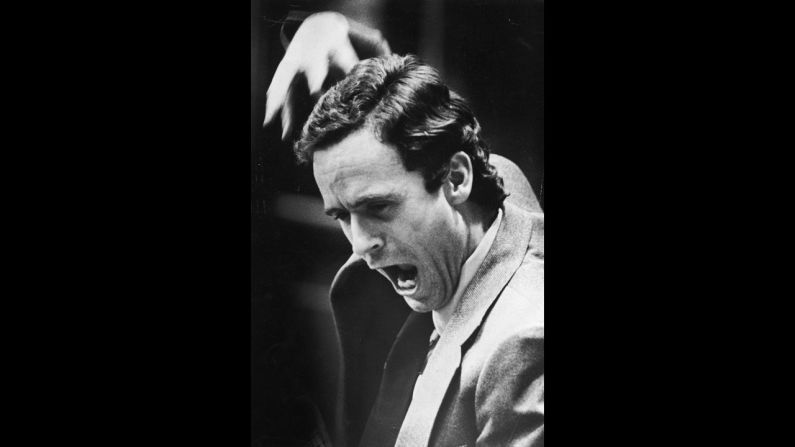

Infamous serial killers

Twenty-eight bodies were found in and around the serial killer’s Chicago home, most of them in a 40-foot crawl space beneath his house and garage. Four others had been thrown into the Des Plaines River.

Yet while authorities believed and the jury agreed that Gacy was responsible for all these deaths, that didn’t mean they knew who all of them were.

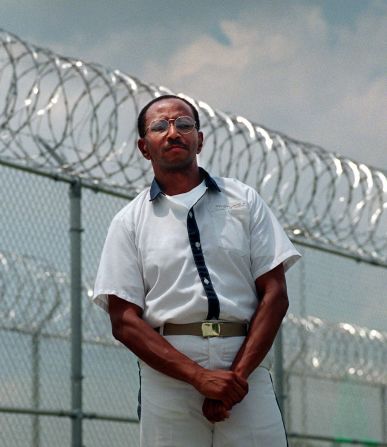

That was the case in 2011, seven years after the serial killer was executed, when the Cook County Sheriff’s Office launched a new effort to identify eight of the victims.

This time, they’d use new technology to obtain DNA profiles, an effort they hoped would provide closure to families looking for their loved ones for decades.

Sheriff: Case shows ‘never give up’

Only of those eight Gacy victims, William George Bundy, has been positively identified as a result.

The Cook County Sheriff’s Office said in a news release Wednesday that 12 cases have been closed as a result of Gacy-related leads, in part because relatives of missing people from that era and area came forward with new information at the urging of authorities.

In five cases, once-missing people were found alive and were reunited with their families. Two others died of natural causes after they were reported missing. And there was some resolution for four other instances – Drath being one of them.

Wertheimer, his maternal half-sister, reached out to the Sheriff’s Office and submitted DNA thinking that Drath – as a young white male from Chicago’s North Side – fit the profile of Gacy’s other victims.

Investigators weren’t able to link her to any of Gacy’s known victims, but her information was uploaded to a federal DNA database. DNA from Darth’s tissue samples was uploaded in late 2014, though it wasn’t until May 2015 that this was matched with Wertheimer. Dental records and a tattoo with the name “Andy” confirmed the connection.

Wertheimer learned of the link on September 10, and San Francisco police are now trying to find the killer – not of John Doe No. 89 but of Andre “Andy” Drath.

“I’m thankful that Andy Drath will be brought home and laid to rest with the dignity he deserves,” Cook County Sheriff Thomas Dart said. “This breakthrough illustrates that we should never give up on a cold case, no matter how hopeless it appears.”