Story highlights

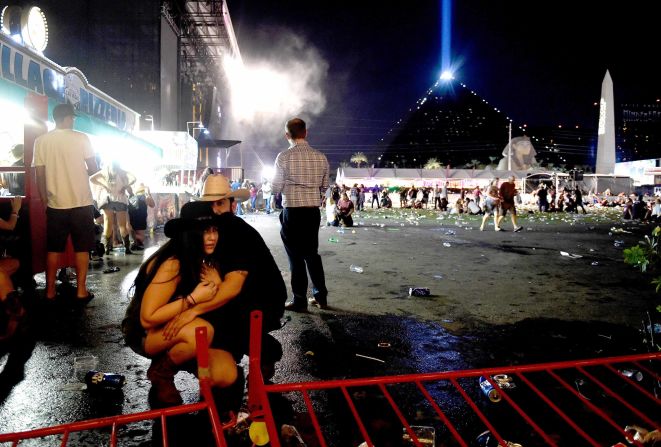

A study finds that mass killings spread contagiously

The window for copycat killings lasts about 13 days

Experts say availability of handguns, media coverage is to blame for spike in U.S. mass killings

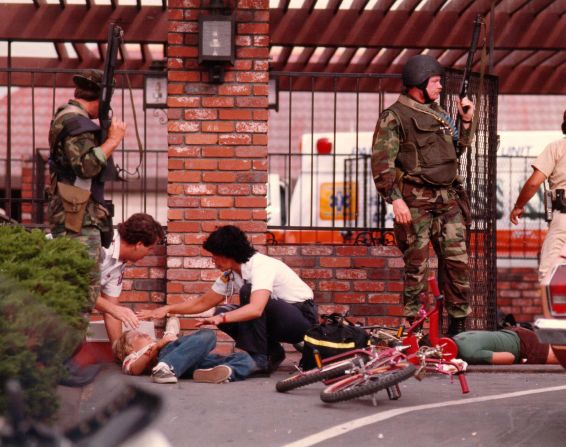

Mass killings and school shootings spread “contagiously,” a study found, where one killing or shooting increases the chances that others will occur within about two weeks.

The study, published in July the journal PLOS ONE, found evidence that school shootings and mass killings – defined as four or more deaths – spread “contagiously,” and 20% to 30% of such killings appear to be the result of “infection.” The contagion period lasts about 13 days, researchers found.

Researchers gathered records of school shootings and mass killings from several data sets and fit them into a mathematical “contagion model.” The spread they found was not dependent on location, leading researchers to believe that national media coverage of a mass shooting might play a role. On average, mass shootings occur about once every two weeks in the United States and school shootings happen about once a month, the study said.

The massacre that didn’t happen

“What we believe may be happening is national news media attention is like a ‘vector’ that reaches people who are vulnerable,” said Sherry Towers, a research professor at Arizona State University and lead author of the study.

Those vulnerable people are those who have regular access to weapons and are perhaps mentally ill, Towers said. Once “infected” with knowledge of a shooting from national media coverage, data shows that a person is more likely to commit a similar crime.

“When at least three people are shot, but less than four people are killed, the media reports tended be local,” Towers said. These shootings that received local news coverage, but no national news coverage, did not have the same contagious effect, according to Towers.

Related: Why U.S. has the most mass killings

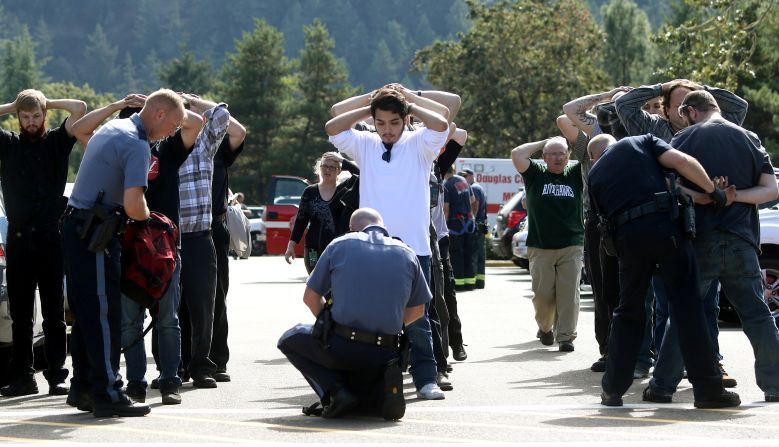

Katherine Newman, provost of the University of Massachusetts Amherst and co-author of “Rampage: The Social Roots of School Shootings,” said media coverage may prompt copycat crimes, but shining the national spotlight on mass and school shootings can have benefits, too. It encourages students and adults to come forward with information about suspicious people.

More tips from the public means a greater chance that tragic mass killings can be prevented, said Newman, who was not involved in the study.

“While there’s a spike in shootings following an incident, there’s an even bigger spike in reported plots,” Newman said. “This is because people are vigilant and come forward with their suspicions and concerns.”

Newman said the biggest hurdle to preventing school shootings is making it possible for people with information to report to authorities.

“If we want kids to come forward with information, we have to remind them these horrific crimes are happening,” Newman said. “It should be part of a regular school curriculum to remind kids these things are going on.”

Related: The Loneliest Club – the survivors of gun violence

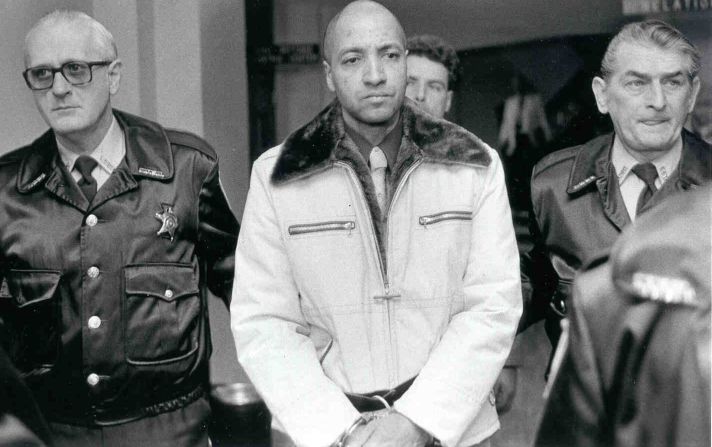

Jack Levin, a criminologist at Northeastern University, said it’s the amount of media coverage that matters.

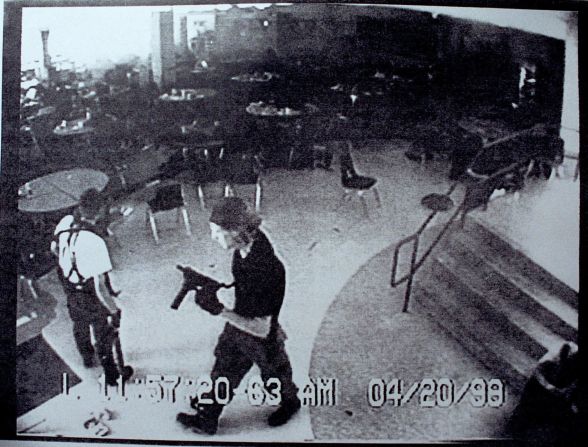

“It’s the excessive media attention that creates the copycat phenomenon. We make celebrities out of monsters,” Levin said, noting that there are trading cards, action figures and magazine covers featuring murderers.

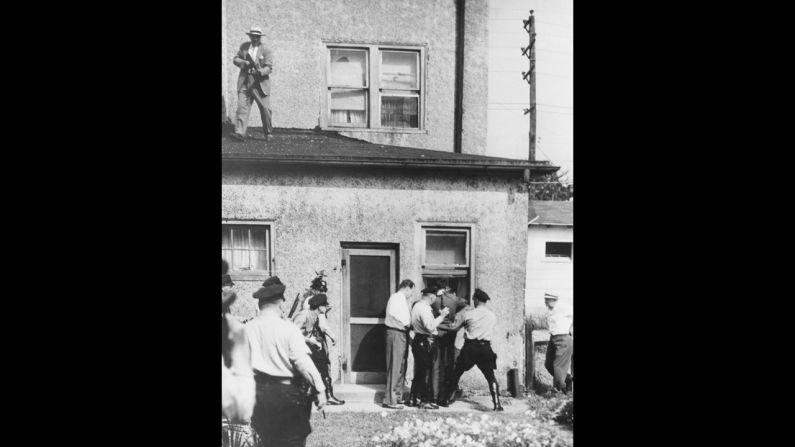

Researchers behind the new study also found that states with higher gun ownership were more likely to have mass killings and school shootings. On the contrary, states with tighter firearm laws had fewer mass shootings.

Levin said he believes a high number of handguns is partially responsible for the high rate of mass shootings in the United States.

“We have so many semi-automatic weapons that can be easily concealed, and taken from the home and used on classmates or whoever,” he said. “The real problem in (the United States) has to do with handguns being in the hands of the wrong people. But you can’t blame it all on guns. (The United States) leads the Western world in nongun homicides, too.”

Towers knows firsthand the terror that shooting incidents can send through a community. She was traveling to a meeting at Purdue University in Indiana in January 2014 when the campus was locked down after reports of gunshots. Andrew Boldt, a 21-year-old Purdue senior, was fatally shot by another student, Cody Cousins. As details surrounding the shooting slowly emerged, Towers said she felt a mix of worry, relief, guilt – and eventually, curiosity.

“It struck me as odd that other shootings occurred around the same time,” Towers said. “I knew that day that I wanted to look into this further.”

Collecting information about school shootings and mass killings wasn’t easy, Towers said, noting “right now there is no federal database on these tragedies.”

Towers said there are still a number of important questions left unanswered, and creating consistent data about these incidents is the first step.

“An official database needs to be compiled,” Towers said. “The dynamic in the society needs to be addressed so we can fix this public health crisis.”