It was arguably the most powerful emblem of the tournament that changed the way the world saw African football – a Cameroon striker’s joyous dance at a corner flag.

Nobody had really expected all that much of Cameroon at the 1990 World Cup in Italy.

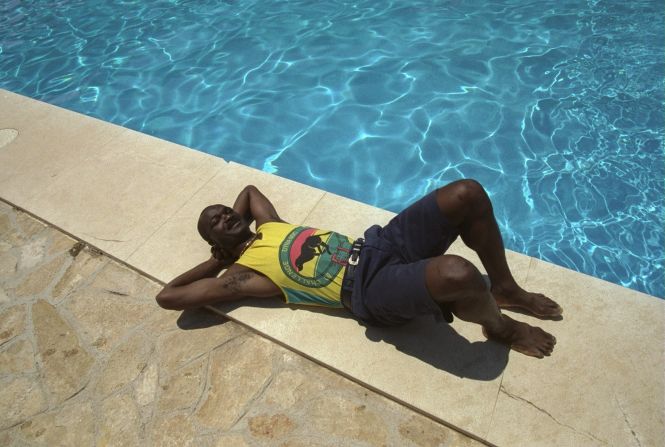

Not many casual observers knew that much about 38-year-old Roger Milla – the football veteran who, after each of his four tournament goals, shimmied his way into the spotlight.

Exactly a quarter of a century ago today Milla was the man on the spot in his side’s last-16 clash with Colombia, scoring twice as a second-half substitute to seal a 2-1 win and continue the Indomitable Lions’ heroics.

After each strike he headed straight for the corner flag, gyrating in front of it in a sort of Makossa dance before being engulfed by euphoric colleagues.

He found that his celebration, almost more than his goals, had caught people’s imaginations – and that it also had a wider and more dramatic effect.

“It remains in our collective memory – it actually changed the perception the world had of African football,” Paulo Teixeira, who was working as a photographer at the tournament, told CNN.

“Milla dancing in front of the corner flag became a hit. It was an image of joy, of positive energy, communication through body language.

“Those goals put Cameroon, and ultimately African football, on the world map.”

Now an agent, Teixeira was born in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo) and has extensively traveled throughout Africa in his work, giving him an in-depth knowledge of the continent’s football development.

The 63-year-old believes the exploits of Milla and friends also began to alter the way in which people thought about footballers’ diets and preparations.

“His, and Cameroon’s, performance made scouts and clubs look differently at African players,” he says. “It was proof that they could physically go beyond all expectations, almost defying science in terms of resistance.

“People started to look at the way African players ate – no bread, no desserts, no booze, no coffee, no smoking. All was natural – vegetables, rice, white meat.”

Milla hadn’t even been supposed to be in Italy for the tournament, having earlier quit the international game and traveled to the Reunion Islands to play his football.

But it turned out he had admirers in high places and was persuaded to reconsider by Cameroon president Paul Biya, who then insisted on his inclusion in the World Cup squad.

The Indomitable Lions faced tournament holders Argentina – Diego Maradona and all – in their opening match.

Milla, the oldest outfield player at the event (only England goalkeeper Peter Shilton was older), played a late cameo role in the occasionally brutal 1-0 win that got Italia 90 off to a sensational start.

But there was plenty more to come from Milla.

Coach Valeri Nepomniachi opted to bring him on earlier in the next group game against Romania, knowing a win would seal his team’s place in the knockout stages.

With 76 minutes of an often tense match gone, Milla won a bouncing ball on the edge of the area, ran on and opened the scoring some 15 minutes after entering the fray. An iconic celebration was born.

Four years later, he would augment his achievements by becoming the oldest-ever World Cup player and goalscorer against Russia in the United States.

But it is Italia 90 with which he – like the host nation’s Toto Schillaci and England’s Paul Gascoigne – will always be most strongly associated.

“It might not have changed his career in financial terms,” Teixeira says. “After all, he was already way past normal football age.

“But he became an icon – and that is something that money cannot buy.”