Story highlights

Supreme Court made headlines in two cases that profoundly affect the lives of millions of Americans

But legal scholars say court's historic role has been to block, not make, social change

Does court defend wealth and privilege? Defenders say court reflects will of people

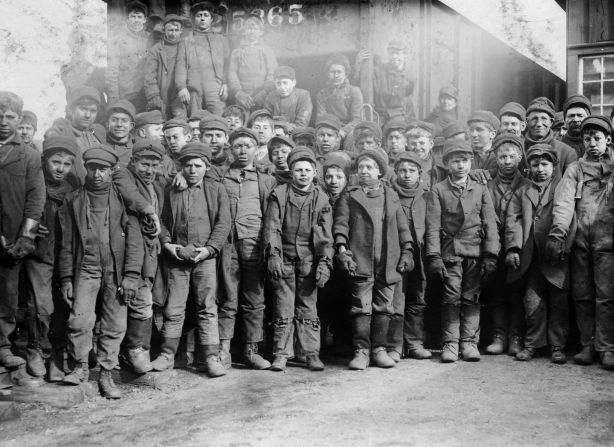

He was a poor, frail teenager who would have melted away into history, but Reuben Dagenhart became the central character in one of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most notorious cases.

He worked 60 hours a week in a North Carolina textile mill, earning 10 cents a day. The work scarred his lungs and stunted his growth. It was 1916, and Dagenhart was just one of millions of child laborers who worked in dangerous mines, dank sweatshops and textile mills in early 20th-century America.

The U.S. Congress had just passed a law banning child labor after a national movement was launched to stop the practice. Southern cotton manufactures, though, recruited Dagenhart’s father to file a lawsuit claiming the new law unjustly deprived him of his son’s wages.

The Supreme Court heard the case and ruled in 1918 that the law was “repugnant to the Constitution” because it violated states’ rights and exceeded Congress’ power to regulate commerce.

Dagenhart returned to the textile mills, as did millions of other American children whose lives were damaged by the ruling. The Dagenhart decision offers a lesson about the Supreme Court not found in many civics textbooks, some legal scholars and observers say: The court’s historical role has been to block political and social change, not validate it.

“It took an extra 20 years to do away with child labor,” says Garrett Epps, a constitutional law professor at the University of Baltimore School of Law and a contributing editor for The Atlantic. “That’s 20 years of children coughing their lungs out in textile mills or dragging wagons of coals underground instead of going to school because the court chose to distort the Constitution that way.”

The Supreme Court made headlines this week in two cases that profoundly affect the lives of millions of Americans: It ruled 5-4 that same-sex marriage is legal nationwide and voted 6-3 to uphold health care subsidies for millions enrolled in Obamacare.

The decisions are part of a ritual every June: As the high court ends its session, the media hypes the most controversial cases, legal pundits make their predictions and commentators explain how each decision will change the country.

But is the Supreme Court’s mission really about change – or making sure change never happens in the first place?

Forget any notion of looking to the Supreme Court for boldness, say Epps and others. The court has defended the status quo throughout much of its history, usually ruling in favor of “wealth, power and privilege.”

“The dominant historical role for the court for all but a very brief period has been to be a conservative force,” says Epps, author of “Wrong and Dangerous: Ten Right-Wing Myths about Our Constitution.”

Not so fast, say other court observers. What about all the welfare programs and regulatory agencies the court has left standing?

Besides, if the court is slow to make change, that’s because the Constitution itself is a conservative document, they say. The court eventually comes around, changing with the times just as the American people do.

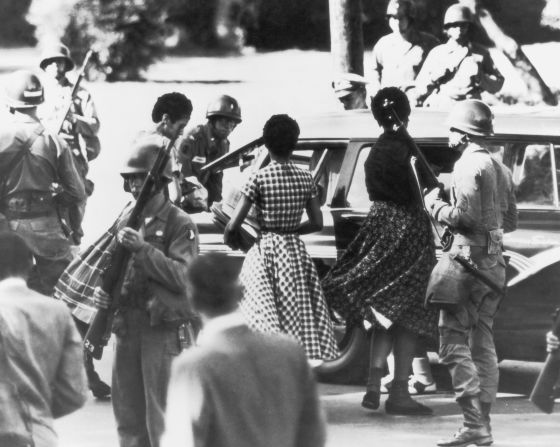

Both sides cite one of the Supreme Court’s most revered rulings to make their point: Brown v. Board of Education. The court’s 1954 decision ordered public schools to end state-sponsored segregation at a time when much of America accepted racial segregation.

Critics see it as evidence of the court’s inability to enforce its decisions. But defenders see something else:

“Was the Supreme Court perfect on this issue?” asks Clark Neily, an attorney with the libertarian public interest law firm Institute for Justice and author of “Terms of Engagement: How Our Courts Should Enforce the Constitution’s Promise of Limited Government.”

“Of course not. But was it better than the other branches of government and society in general? I would say so.”

Does the court inflict suffering?

Those who say the nation’s top court has tended to block change point to its makeup. Judicial radicals don’t survive the lengthy vetting process that leads to a Supreme Court appointment. And virtually all of the court’s members have been white judges from privileged backgrounds, they say.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the 19th-century French political scientist whose classic study of American democracy is still quoted today, called the legal profession the last bastion of America’s aristocracy, says Ian Millhiser, author of “Injustices: The Supreme Court’s History of Comforting the Comfortable and Afflicting the Afflicted.”

“If you’re a lawyer of the caliber that gets on the Supreme Court, you’re probably very well off,” Millhiser says.

Tocqueville said leaders in America’s legal profession are instinctively suspicious of dramatic political change, Millhiser recounted in his book.

Tocqueville wrote that lawyers are “secretly opposed to the instincts of democracy” – that their “superstitious respect for what is old” is in opposition to democracy’s “love of novelty; their narrow views, to its grandiose plans; their taste for formality, to its scorn for rules; their habit of proceeding slowly, to its impetuosity.”

This suspicion of democratic change has caused the court to be on the wrong side of history numerous times, Millhiser writes. The Supreme Court issued decisions that legitimized Jim Crow segregation, approved of the forced sterilization of a woman against her will, forced Japanese-American citizens into internment camps during World War II, and with its 2010 Citizens United v FEC decision, “gave billionaires a far-reaching right to corrupt American democracy.”

The Supreme Court has not just ignored human misery; it’s caused it, Millhiser says.

“Few institutions have inflicted greater suffering on more Americans than the Supreme Court of the United States,” wrote Millhiser, a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress Action Fund and a columnist for its political blog, ThinkProgress.

Virtually all Supreme Court justices have been men, and critics say the court has, at times, been blind to the rights of women. President Ronald Reagan appointed Sandra Day O’Connor as the first woman to the nation’s top court in 1981. The current Supreme Court includes three women.

The contemporary Supreme Court has determined that sexual discrimination is contrary to American values. But paternalistic language still crept into one of the court’s biggest decisions recently, says Emily Martin, vice president and general counsel for the National Women’s Law Center in Washington.

In 2006, the court upheld a law that banned a type of late-term abortion. In the court’s majority opinion, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote that “some women come to regret their choice to abort the infant life they once created and sustained.”

Martin called it a “disturbing analysis.”

“It played into a stereotype that the Supreme Court had rejected, the notion that you could make laws that could restrict women’s rights based on assumptions that you’re protecting women from their choices,” Martin says.

Authority without power

The court has been an enemy of change because the Constitution is hostile to change as well, others say.

Gerald Rosenberg, a University of Chicago law professor, says the Constitution is a conservative document that protects private control over the allocation of resources. It doesn’t provide for basic rights such as education and health care. Progressive movements that sought social change often couldn’t point to a specific constitutional passage that affirmed their goals.

“If you’re on the left and you are trying to find a right, typically the Constitution doesn’t state it,” says Rosenberg, author of “The Hollow Hope: Can Courts Bring About Social Change?”

“You have to argue by implication. You are always working with a document that wasn’t designed to further or protect your interests.”

Leaders of progressive moments often have avoided going to the Supreme Court because of its limitations, Rosenberg says. They knew that social and political change came primarily from movements that pressured politicians into passing laws, Rosenberg wrote in a 2005 University of Chicago law journal article titled “Courting Disaster: Looking for Change in All the Wrong Places.”

“They understood that judges, and the courts in which they served, were dedicated to preserving the status quo and unequal distributions of power, wealth and privilege,” Rosenberg wrote.

People also should be wary of looking to the court for change because even in those rare moments when it tries to create change, it fails because it has no power to enforce its decisions, he says.

Look at Brown v. Board of Education, he says.

Southern school districts ignored the decision for years. What forced them to abandon state-sanctioned segregation wasn’t the high court’s edict – it was two laws, the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965, he says.

The 1964 Civil Right Act declared that no “program or activity” that discriminated could receive federal financial assistance. And the 1965 law sent federal money to support education in the poorest states, many of which were in the South. The federal government told Southern school districts that if they didn’t desegregate, they wouldn’t receive federal money, Rosenberg says.

“Now the courts could step in and take the money away,” Rosenberg says. “That’s what did it.”

Proof of social change

If the court functioned like the legal embodiment of Ebenezer Scrooge, one legal scholar asks, then how does one explain the rise of the modern American welfare state that began with the New Deal, the programs created by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to pull the nation out of the Great Depression?

The Supreme Court could have struck down many programs that help the less fortunate, such as Social Security and Medicare, but it did not, says Neily, the libertarian Institute for Justice attorney.

Many of those government programs depend on a redistribution of income – a transfer of resources from wealthy Americans to the poor and middle class – but the high court has not ruled them unconstitutional, he says.

“The advent of the American welfare state during and after the New Deal is another example of a political reform movement that the Supreme Court neither stopped nor significantly slowed,” Neily says.

If the court defends wealth, power and privilege, it could have declared the entire federal bureaucracy unconstitutional, Neily says.

“Surely the stereotypical rich factory owner or oil tycoon would prefer to operate free of scrutiny from the EPA, FDA, EEOC, OSHA and all those other alphabet-soup agencies … and yet the courts have left the federal administrative apparatus largely – though not completely – untouched,” Neily says.

The court’s impending decision on same-sex marriage is also proof it is not an implacable foe of social change, Neily says.

In the 1986 case Bowers v. Hardwick, the Supreme Court ruled there was no constitutional right for consenting gay adults to engage in private, consensual sex. But in 2003, the Supreme Court overturned the Hardwick decision, ruling in Lawrence v. Texas that sodomy laws were unconstitutional. And in 2013, the court rejected a key section of the federal Defense of Marriage Act, which denied federal benefits to legally married gay and lesbian couples. By then, 35 states had passed laws banning same-sex marriage.

“That surely qualifies as a significant political reform movement,” Neily says of the gay rights struggle, “and it appears the Supreme Court has, if anything, been ahead of public opinion on that issue.”

The higher power the court answers to

Another legal scholar says the Supreme Court doesn’t block popular will; it actually confirms it.

The court may block social or political change for a short time, but ultimately it changes with the times because it answers to a higher power: the American people, says Barry Friedman, a constitutional law professor at New York University School of Law.

The Supreme Court has abandoned decisions that have become unpopular and retreated from others that have lost favor with the American public because justices won’t stray too far from popular opinion, says Friedman, author of “The Will of the People.”

He, like Neily and Rosenberg, also cites the court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision.

In Brown, the court ordered the nation’s public schools to desegregate with “all deliberate speed.” But the American public resisted school integration efforts such as busing for many years, Friedman says.

In 2007, a conservative majority on the Supreme Court cited Brown when it struck down a public school’s attempt to encourage racial integration. In a 5-4 ruling, it declared that a public school district in Seattle couldn’t consider race when assigning students to schools, even for purposes of integration.

The American public had already become ambivalent about school integration before the Seattle decision, Friedman says. The court just reflected those second thoughts.

Today, many public schools across America have essentially re-segregated after years of protests and the lifting of court-ordered desegregation plans.

“Over a period of time, the court doesn’t stand in the way of an organized public,” Friedman says. “The issues that the people are paying attention to, the court will come in line with public opinion.”

The belief in the power of the people could be seen in the eventual triumph of the child labor movement. After the Supreme Court struck down the law banning child labor in 1918, the child labor movement persisted. And 23 years later, the court outlawed compulsory child labor with its United States v. Darby decision.

What happened, though, to the North Carolina teenager who became the focal point of the battle over child labor?

A reporter tracked down Reuben Dagenhart six years after his father’s Supreme Court victory. He asked the then-20-year-old Dagenhart what he had gained from the decision. Millhiser, author of “Injustice,” recounts how Dagenhart responded:

“Look at me!” Dagenhart said. “A hundred and five pounds, a grown man and no education. I may be mistaken, but I think the years I’ve put in the cotton mills stunted my growth. They kept me from getting any schooling. I had to stop school after third grade and now I need the education I didn’t get.”

Change may or may not come from the Supreme Court, but for some people, it never came soon enough.