Editor’s Note: Kelly Wallace is CNN’s digital correspondent and editor-at-large covering family, career and life. Read her other columns and follow her reports at CNN Parents and on Twitter.

Join the conversation: CNN Parents will host a Facebook chat with parents and experts on mental illness and addiction from 1-2 p.m. ET on Monday, June 22.

Story highlights

Daniel Montalbano, 23, spent 8 years trying to cope with mental illness and drug addiction

Nearly 9 million people are mentally ill and abuse substances, according to federal agency

Barbara Theodosiou anxiously awaited each text and call. Still, her stomach turned every time her phone would ring or vibrate. Every time there was a knock at the door.

Sometimes, she would even turn her phone off at night – the fear of getting that life-altering news too much to bear.

She lived with that terror for eight years as her beloved son Daniel Francis Montalbano, a boy whom she says “painted, wrote poems and told his mother endlessly how much he loved her,” struggled with mental illness and drug addiction.

In April, after Daniel had gone missing for about a week, her phone rang with a police sergeant at the other end of the line. She immediately called out to her husband to get on the phone with her.

“I never wanted to be alone to find out something happened to Daniel,” she said during a phone interview from her home in Davie, Florida.

Being an addict’s mom: ‘It’s just a very, very sad place’

It was the call she feared most.

Daniel, just 23, was gone. He had drowned in Florida’s Intracoastal Waterway, she learned.

Her life, like the lives of parents too numerous to count who have also lost children to addiction, was forever changed.

“There is no peace for me. Ever again. This is a life sentence,” she said in a speech paying tribute to her son during a special event in her town in honor of The Addict’s Mom, the Facebook community she founded in 2008 to support families battling the disease of addiction.

“It shocks me. It crushes me. It steals my soul,” she said. “There are no breaks, no holidays, there is no solace here. And I spend every second wishing I had one more moment, one more day with my son before drugs.”

But despite her grief – and perhaps because of it, she is more determined than ever to make sure that Daniel’s life was not lived in vain.

She is now committed to telling his story and raising awareness to help people dealing with both mental illness and substance abuse and pushing for reforms in schools and prisons to make sure they get the treatment they need.

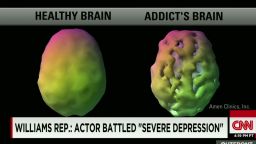

The numbers don’t lie – mental illness and substance abuse often overlap.

Nearly 9 million people have co-occurring disorders, meaning they have both a mental and substance abuse disorder, according to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration.

But only 7% of them get treatment for both conditions, with a staggering 56% receiving no treatment at all, the agency says.

Add in a justice systemthat isn’t always equipped to handlemental illness, and you have a recipe for disaster, Theodosiou says.

The Addict’s Mom

I got to know Theodosiou last year as I reported a lengthy story on the mothers of addicts, revealing how they cope with the incomprehensible challenges of supporting their addicted child while not enabling their disease.

As the founder of The Addict’s Mom, which now boasts 30,000 members and chapters in every state, Theodosiou, a successful entrepreneur,was a natural person to interview. She has devoted her life to helping those affected by addiction.

She came to this mission not by choice, she says, but after learning – during a six month span – that two of her children were addicts.

Addiction: The disease that lies

Her eldest son Peter, now 26, started using prescription drugs and then escalated to heroin. He has been in recovery for 4½ years, graduated college and plans to start graduate school this fall.

At 15, Daniel started what’s called robotripping, where he would take large quantities of cough medicine to get high.

Theodosiou believes Daniel turned to cough medicine, which he continued to abuse until his death, to cope with the pain of mental illness.

Ever since Daniel started elementary school, he struggled socially, said his mom. He was bullied, ostracized, disruptive in the classroom. By middle school, he was sad and becoming angry.

“I took him to a psychiatrist at the tender age of 12,” said Theodosiou. “There was no definitive diagnosis.”

Was it attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder? Obsessive-compulsive disorder? Bipolar disorder? Asperger’s syndrome? Theodosiou says she’ll never know for sure because as Daniel started abusing drugs, he was never sober long enough to really get to the root of the problem.

When he was younger, one doctor said he might have ADHD and suggested medication, but Theodosiou decided against it. Her brother was a heroin addict, and she worried about her children taking medication and eventually becoming addicted.

“My kids were young. I didn’t really want to start them on medication. I was really scared,” she said.

She now wonders about that decision.

“It might have been effective, but I don’t know. I’ll never know.”

Theodosiou says there were no mental health resources in Daniel’s schools. When students would complain about him, he would be put in detention, sitting by himself in another room, she said.

iReport: From a heroin-fueled bank robber to a family man – a story of recovery

“Years later, he would begin to tell me that that really broke him,” she said. “As he started to use drugs, what he would say to me when I would go to the hospital … ‘Mom, I only want to be normal.’ “

Her son, she says, was part of a “broken system, a broken mental health system since he was a little boy, and that system failed him.”

The challenges for the mentally ill who abuse substances

People who are mentally ill and abuse substances are at “increased risk of impulsive and potentially violent acts,” according to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI).

They’re also less likely to achieve lasting sobriety, more likely to become physically dependent on their substance of choice, and to end up in legal trouble from their substance abuse, according to NAMI.

The legal system, says Theodosiou, failed her son too.

When I interviewed Theodosiou last year, Daniel had been in rehab for five weeks – at that time his longest period ever in treatment – but had relapsed. He’d broken the condition of his release from jail and was back behind bars.

The “horrific cycle” would continue, she said.

It would go something like this: Release from jail. Overdose. Emergency room. Psychiatric wing. Treatment. Relapse. Arrests for petty crimes. Back to jail.

Prescription drug abuse: There is help

Then, last fall, while Daniel was in the psychiatric wing of the St. Lucie Medical Center, he was charged with a felony for allegedly assaulting a security guard.

According to the arrest affidavit, Daniel was screaming and causing a disturbance in the dining area. The document says two security officers made contact with Daniel and tried to use verbal commands to “de-escalate” the situation. Daniel allegedly attempted to hit them several times with a closed fist, and struck one of the officers in the chest with his fist.

“My son was in a psychiatric unit. He was psychotic. He could have easily been given a shot,” said Theodosiou. “The police came and arrested him. He was given a felony. He ended up in jail with violent, violent felons.”

How could someone who is mentally ill and is being treated in the psychiatric wing of a hospital be arrested, asks Theodosiou.

Daniel had never been charged with a felony before. His previous arrests were all for petty crimes and misdemeanors: shoplifting, loitering, public intoxication, misdemeanor battery, said Theodosiou.

Now she – along with help from other moms from The Addict’s Mom – is hoping to convince the Florida State Legislature to consider a bill that would make it illegal to arrest and take to jail a person who is in a psychiatric hospital or a psychiatric unit of a hospital.

“I don’t want to see anyone arrested (who’s) mentally ill in a psychiatric unit,” said Theodosiou. “It’s awful.”

How to differentiate ‘bad’ from ‘mad’

Dr. Harold Bursztajn, co-founder of the Harvard Medical School Program in Psychiatry and the Law, has been a practicing forensic and clinical psychiatrist for over 30 years. He has devoted much of his career to the field of therapeutic jurisprudence, which is centered on assuring that when the legal system does get involved, it doesn’t make matters worse for people who are mentally ill.

Bursztajn believes the most sensible way to proceed, when someone in an in-patient facility is arrested and moved to the criminal justice system after a violent outburst, is for a forensic psychiatrist to conduct an evaluation to differentiate “bad from mad.”

“The fundamental dilemma is to distinguish those people who are mad because of their addictions versus those people who are simply bad and are using their addictions as part of self-gratification rather than self-medication, so there’s a fundamental distinction,” said Bursztajn, who is also an associate clinical professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School.

Bursztajn believes more education is needed throughout the criminal justice system; attorneys, judges and prison officials need to understand how to look for and factor in mental illness when someone is arrested for a crime.

“The key is that education and evaluation precedes disposition. The focus all too often is simply jumping to a disposition without the appropriate evaluation, because the level of education in the prison system, in the justice system, is just not there,” he said.

“I have met some wonderful (prosecutors) who really, really understand this, and (who) work with the defense attorneys and forensic psychiatrists and come up with a treatment plan that actually works,” said Bursztajn. The more prosecutors, defense attorneys and judges who understand this, the better, he added.

What Theodosiou hopes to call attention to is the treatment of people behind bars who are mentally ill and addicted.

Often, Daniel would end up in isolation for his own protection, she said. Theodosiou claims her son wouldn’t have access to therapy, medication or physicians to treat either his mental illness or his substance use.

“And he came out worse,” she said. “Every time he came out, he was angrier. He was more paranoid.”

Unintended consequences: Why painkiller addicts turn to heroin

The St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office, in a statement to CNN, said Daniel “received appropriate medical/mental health treatment” while he served time at the St. Lucie County Jail.

Mark Weinberg, public information officer for the St. Lucie County Sheriff’s Office, said Daniel was evaluated by mental health professionals and prescribed medications, and that he was housed in protective custody, meaning he was the only person in a single-person cell, during much of his stay.

Documents show Daniel had requested to be placed in protective custody on more than one occasion.

‘The system is broken’

Some 14% of male jail inmates suffer from a serious mental illness, and that number goes up to 31% for female inmates in jails, according to a 2009 study.

When looking at inmates with a mental health problem, the numbers are staggering: 56% of state prisoners, 45% of federal prisoners and 64% of jail inmates had a recent history or symptoms of a mental health problem, according to the U.S. Department of Justice.

And, for these inmates with mental health issues, isolation can be particularly damaging, researchers say.

While isolation can be psychologically harmful to any prisoner and cause anxiety, depression, anger, paranoia and psychosis, those adverse effects can be “especially significant” for people who have a serious mental illness, wrote Dr. Jeffrey Metzner, clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado School of Medicine, and Jamie Fellner, senior counsel for Human Rights Watch.

In their research paper published in the Journal of American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, they said, “The stress, lack of meaningful social contact, and unstructured days can exacerbate symptoms of illness or provoke recurrence.”

Often, mentally ill prisoners in isolation will need crisis care or psychiatric hospitalization, the authors said. “Many simply will not get better as long as they are isolated.”

Periods of isolation were mentally damaging to Daniel, Theodosiou believes. She doesn’t think Daniel received the mental health treatment he needed while he was incarcerated.

“The system is broken,” said Sherry Schlenke, a volunteer research director for The Addict’s Mom, who lost her own son 1½ years ago after a 20-year battle with heroin. “The criminal and mental health system should be integrated, working together to solve this problem.”

Dr. Bursztajn says what’s needed within the prison system is a “secondary mental health system” where someone who is “at least board certified in psychiatry” can oversee the determination of a treatment plan that focuses both on getting the individual ready before they are released and preparing them for life once they leave jail or prison.

“You create a plan so that the person can receive the necessary treatment, the necessary education, the necessary supports to not only be able to maintain the equivalent of sobriety in the hospital or in the prison system but also outside of it.”

‘They just wanted to make an example’

Theodosiou believes that at the time of Daniel’s death, he worried about going back to jail.

As part of a plea deal for his felony battery charge, Daniel pleaded no contest in December of last year and was sentenced to 1½ years probation, with six months at an in-patient drug treatment facility paid for by his family and the remaining 12 months attending and completing mental health court.

“It’s not like we were leaving this person out to dry,” said Bruce Harrison, the state attorney in charge of St. Lucie County, told CNN.

Harrison said the prosecution originally recommended nine months in the county jail but reduced that sentence as it became aware of Daniel’s mental health issues.

Daniel started at one treatment center and was moved to another to deal with his “specific mental illness,” he said. He eventually was moved to another facility at the request of his family, said Harrison.

Theodosiou said the overall sentence – a six-month in-patient program and 18 months’ probation – was not appropriate or manageable for someone battling mental illness and substance abuse. Daniel belonged in mental health court, she said.

“If he had gone to mental health court, he would have been in treatment. … They have housing, he would have been on medication. (The prosecutors) said no,” said Theodosiou. “If Daniel didn’t belong in mental health court, I don’t know who did.”

Mental health court is a possibility, Harrison said, when the alleged crime is a misdemeanor, and the person can go back on their medication and ultimately the charges can be dismissed. “In this case, it was a felony and deserved punishment,” he said.

But Theodosiou points to an independent forensic psychiatrist’s evaluation of Daniel after he spent five months in jail. That evaluation, which CNN has obtained, recommended that the behavior that resulted in Daniel’s arrest “be viewed within the context of his psychiatric condition” involving both substance abuse withdrawal and his mental disorder.

The psychiatrist said at the time of his arrest that Daniel was prone to “irritability” and “poor judgment,” and had a history of “physical and nonphysical outbursts of rage,” particularly when “unmedicated.”

The evaluation recommended mental health court for Daniel if such a program were deemed available to him. It also recommended placement within a secure psychiatric facility for psychiatric stabilization and treatment followed by outpatient psychological and substance abuse counseling.

Theodosiou says the sentence of 18 months probation and six months in-patient treatment was never going to be doable for “somebody like Daniel (who) goes to a state hospital like 30 times a year and gets arrested because he’s mentally ill, in the street and harmless.”

She continued, “Daniel living with people with his mental illness. There was no way he could make it .”

In a letter she sent to the prosecution team, she wrote, “I pray another family and her mentally ill child will never be subject to the treatment that Daniel was by the prosecution who sadly has very little training or knowledge of the mentally ill.”

The prosecutors, for their part, stand by their handling of Daniel’s case.

“Mental illness is a mitigator on the sentence that we impose,” said Harrison, the state attorney. “What we try to do is rehabilitate folks, but the primary purpose of prosecution is punishment for criminal acts.”

Harrison continued, “I think our office was just. We couldn’t turn a blind eye to the crime and we did what we felt was appropriate and it didn’t work out.”

Said Theodosiou in response, “They just wanted to make an example, and they did.”

The last call

In April, Daniel was not getting along with anyone in the treatment center, said Theodosiou.

He called his mother, upset, saying other residents took his shoes. Daniel yelled and was told the police were coming, so he ran, she said.

By taking off, he violated his probation. “Daniel knew he would go back to jail.”

Daniel eventually called his mother and was “high as a kite,” apparently after drinking alcohol and taking pills, Theodosiou said. This, after 77 days sober for the first time in his life.

She encouraged him to get something to eat and said she would wire him $20 so he’d have money for food.

Theodosiou spent much of the eight years Daniel battled addiction and mental illness grappling with that dilemma of enabling his disease versus cutting him off cold. Even in his final days, she questions that one last parental act of sending him the money.

Was it the wrong thing to do? Could she, as a mom, have done anything differently? Was there more she could have done?

“There is no wrong or right,” Theodosiou told me last summer when I first interviewed her. “But the point is that I believe … after knowing everything I know now, I wish I would have been tougher sooner rather than later.”

After eight years waiting for the texts and calls, and feeling her stomach in knots every time the phone would ring or vibrate, Theodosiou would hear from her son one final time.

“He called me. ‘Mom, I got the $20. I’m going to go eat something.’ And then that was the last I heard from him.”

Theodosiou is still awaiting the toxicology reports to know what was in her son’s system at the time of his death.

“So did he say to himself. ‘I’m taking my life, taking 80 pills and two bottles of wine and just step in the water,’ or did he fall in the water? I will never know. I’ll never know.”

But what she does know is she will spend the rest of her remaining days trying to raise awareness about people who are battling both mental illness and addiction and pushing for significant improvements to treat both.

“When Daniel died, I just promised myself, whoever would listen, I would tell his story and by telling his story, there’s a million other moms just like me, even as we speak, they’re finding out their mentally ill children have co-occurring disorders,” she said.

In that letter she sent to the team that prosecuted Daniel, she wrote, “All I can do now is tell his story to the world in the hopes that I am able to make the smallest change in a broken system that houses the mentally ill in violent jails.”

What do you think is the best way to help addicts who are also mentally ill? Share your thoughts with Kelly Wallace on Twitter @kellywallacetv or CNN Parents on Facebook.