His is a name that lives on.

In the years that followed Arthur Ashe’s retirement, from tennis announced 35 years ago Thursday, he once said: “I don’t want to be remembered for my tennis accomplishments.”

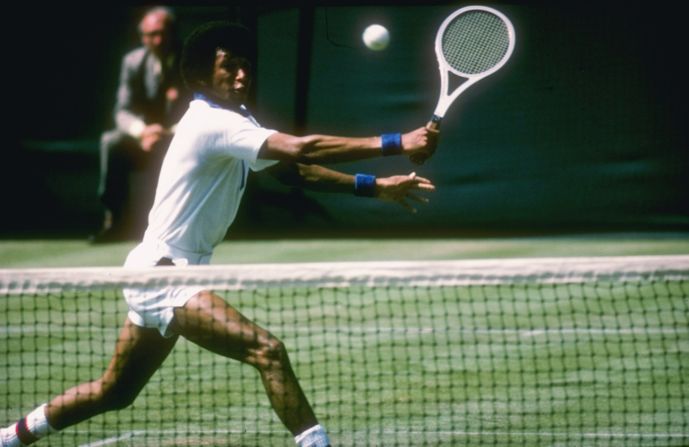

Ashe won the 1968 U.S. Open – the first time it had been staged as an open event. He won the Australian Open in 1970 and, five years later, triumphed over the heavily-backed Jimmy Connors to win the Wimbledon title and become world No.1. He appeared in four other Grand Slam singles finals.

These are pretty memorable tennis accomplishments in anyone’s book. But in Ashe’s case, they are only a small part of the story.

His was a life that encompassed civil rights activism, campaigning for social change and educating people about HIV and AIDS, the virus that took his life in 1993. He was only 49 years old.

And his is a name that lives on. The main court at New York’s Flushing Meadows, the home of the U.S. Open, is named after him, and before the start of each year’s tournament the venue hosts the Arthur Ashe Kids’ Day.

As his widow Jeanne Moutoussamy, talking to CNN’s Open Court program in 2013, put it: “It makes me very proud that Arthur has his name raised up for kids who didn’t have a clue who he is.

“The game of tennis really just gave him a platform to speak about the issues that he cared so much about. I think he was a role model for a whole lot of kids, which is why his legacy is so important to promote today.

“We don’t want a whole generation of kids today – and generations to come – to not know that he was more than a tennis player.”

Ashe, whose play boasted a combination of finesse and bravery, was born in the segregated South in Richmond, Virginia, in 1943.

His first experience of tennis came at a blacks-only playground in the city, and his natural flair for the game earned him a tennis scholarship to the University of California in 1963 – the year in which he also became the first African-American to represent the United States in the Davis Cup.

Read: Arthur Ashe – Sport’s greatest black icon?

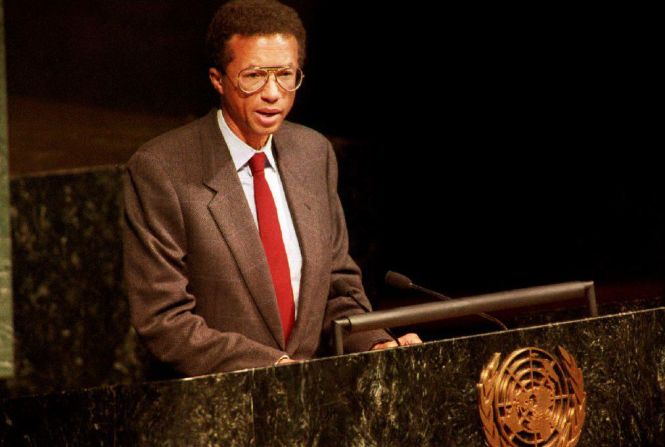

In 1970, he was denied a visa by South Africa’s apartheid regime, preventing him from competing in the country’s national open. He campaigned for South Africa to be excluded from the International Tennis Federation but he was able to play there in 1973 – the first black male to do so.

When Nelson Mandela was freed in 1990 after serving 27 years in prison, Ashe returned to South Africa and said: “When I think of him, my own political efforts seem puny.”

By then, he was 11 years into his retirement from tennis. In 1979, he had suffered a heart attack and undergone a bypass operation. Further complications had made it impossible for him to go through with plans to return to the tour.

Retirement didn’t mean an end to involvement – Ashe became captain of the U.S. Davis Cup team – but in 1983, he underwent further heart surgery. During that operation, it is believed that he was given an infected blood transfusion from which he contracted HIV.

The virus was not diagnosed until 1988, with the diagnosis initially kept private. But in 1992, braving a climate of opinion towards HIV that was overwhelmingly driven by fear and hostility, Ashe went public at a press conference after a newspaper had contacted him to ask about his condition.

With the fearlessness that characterized his life, he campaigned to educate people about the illness and back attempts to find a cure, setting up the Arthur Ashe Foundation for the Defeat of AIDS in 1993, his final year.

In that year, Ashe – also a fine writer whose three-volume book” A Hard Road to Glory” told the story of black Americans in sport – completed an autobiography, “Days of Grace.”

When most sportsmen and women call time on their careers, what they did in their field is what dominates the way they are remembered.

But that’s not the case with the extraordinary Ashe. As his widow concluded, he was “more than just an athlete, more than just a patient, more than just a student and a coach.”