Story highlights

Former Texas judge says Durst case "affected me in many, many ways"

Durst is charged with first-degree murder in the slaying of his longtime friend in 2000

More than two decades as a judge, prosecutor and defense lawyer could not prepare Susan Criss for the Texas murder trial of millionaire Robert Durst.

The aftermath of the sensational 2003 trial of the scion of a New York real estate empire in many ways upended the life of the 54-year-old Galveston County-born lawyer who presided over the case. Durst admitted at trial that he killed neighbor Morris Black in Galveston and chopped up the body.

There was the awkward encounter with Durst in an upscale Houston mall in 2005. Durst had already been acquitted after his attorneys argued that he killed Black in self-defense.

Or the time, month’s later, when the severed head of a cat was left near the doorstep of Criss’ home. Criss said she believes Durst was behind it but admits police found no evidence. Fearing for her life, Criss said she stashed handguns throughout her house in case of a home intrusion. She put away the butcher knives in her kitchen.

There was the strange instant message that she said brought FBI agents and surveillance cameras to her home.

“I’ve been living with this,” the former judge said in an interview Friday. “It’s affected me in many, many ways.”

‘It’s not personal’

The emotions came rushing back when Durst – the focus of HBO’s true crime documentary series “The Jinx” – was charged with first-degree murder this week in the 2000 killing of his longtime confidante, Susan Berman. Durst’s lawyer has denied his client was involved in Berman’s death.

“Everything he does is totally unexpected,” she said.

Durst, 71, appeared to be preparing for life on the run when FBI agents arrested him in a New Orleans hotel on Saturday. In his room, agents found more than $40,000 in cash, a handgun, marijuana and a neck-to-head latex mask to alter his appearance. He’s being held on drug and weapons charges in Louisiana as he awaits extradition to Los Angeles.

The last time Durst was accused of murder was in Galveston. Though he was acquitted in the death of his neighbor, Durst later served nine months in prison on felony weapons charges stemming from that case.

Days before Christmas 2005, Criss ran into the man whose real estate developer family is among New York’s wealthiest at Houston’s The Galleria mall.

Durst, who was on parole at the time, was on his cellphone. He had his head down. “I was glad because I could get my composure,” Criss recalled.

It was the first time Criss had seen Durst outside court, “in the free world,” as she put it.

“I needed to not show any fear,” she remembered thinking. “I got my poker face on.”

“Hey, I know you,” she said Durst told her.

‘Genuinely touched’

He appeared startled and dropped his phone.

Fumbling to pick up the pieces of his phone, Durst said, “You’re Judge Criss. I did not recognize you without the robe,” she recalled.

“How are you doing, Bob.”

Durst told her that he couldn’t believe she stopped to talk to him.

“I have a job to do but it’s not personal.”

There was small talk about cases Durst’s lawyers were working.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, how do I get out of this? How do I exit,’” said Criss, who then wished Durst a happy holiday.

Durst said he was impressed that she had stopped to chat.

“He seemed genuinely touched,” Criss said.

She turned around and walked away. She wanted to look back at him but didn’t want to seem concerned.

“I started calling my mom and staff and my friends – You’re not going to believe who I saw? They said I should call security. For what? To tell them he’s shopping.”

‘Justice isn’t going to be done’

The Galleria mall was not listed on the places Durst could go during his parole, said Criss, who was a witness at a subsequent parole hearing.

The former judge said police officers told her that Durst had also been spotted outside the home where Morris Black was killed. A secretary in the district attorney’s office saw Durst driving behind the Galveston courthouse, Criss said.

A condition of Durst’s parole was that he could only visit places where his parole officer permitted him, Criss said. His parole was not revoked.

When court officials called Durst’s lawyer Dick DeGuerin to inquire about his presence near the courthouse, the lawyer said his client was visiting a psychiatrist in the area.

DeGuerin could not be reached Friday for comment about what Criss said about his client.

“There could be no good reason to come back to these places,” Criss said. She started to become concerned.

In “The Jinx,” Durst described the time he spent living in Vermont with his first wife, Kathleen, running a health food store in the 1970s.

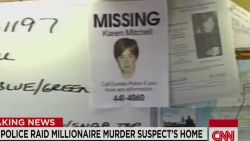

In 1982, Kathleen McCormack Durst went missing. Durst said he last saw her when he dropped her off at a train station in Katonah, New York, and she headed to their Manhattan apartment. Her family said they believe she’s dead and that Durst is to blame. The case has never been solved. Durst has denied any involvement in her disappearance.

‘In a panic’

“It’s a nightmare watching it unfold because you could see that justice isn’t going to be done,” Criss said of the Durst case and its many tentacles.

One day in June 2006, Criss said, that nightmare arrived on a walkway just feet from the doorstep of her home. She blames Durst.

“It was part of severed cat and it had been cut right behind the shoulders,” Criss said. “So it had the head and it had the two front legs. It was a small, pretty little gray cat. It was placed very carefully. It wasn’t just tossed. It was very neatly laid there. It was perfectly cleaned. This had obviously had been killed somewhere else and brought here.”

The animal’s head was perfectly severed.

“What was the key piece of evidence in our case that wasn’t there that would have given no doubt whatsoever that this was not self-defense – the severed head,” Criss said, referring to Morris Black, whose dismembered body was recovered but not his head.

Criss thought of the two dachshunds she had at home. She checked and the dogs were fine.

“I was in a panic,” she recalled. “I was just distraught.”

Guns all over the house

The police were contacted. Even the Galveston police chief arrived at the scene, Criss said. A veterinarian determined that the cat had been killed by a person. Forensic tests found no DNA under the claws. There was no evidence linking Durst to the incident.

“They thought I was paranoid and crazy, that I was overreacting,” Criss said.

Galveston Det. Rick McCullor said he was part of the investigation but declined to comment further.

In an email to the Bonnie Quiroga, head of the Galveston Office of Justice Administration, Criss talked about getting blinds for her windows and cameras for the courthouse. She recommended getting the door locks fixed. CNN obtained a copy of the email.

“His message is he knows where I live (and) this is what he is capable of,” she wrote.

Criss said she thought about evidence at the murder trial. The medical examiner testified that the person who dismembered Black knew exactly what tools cut through muscle and bone.

Then the judge started receiving instant messages from unknown senders. One said, “Did you like your package?”

Criss contacted the FBI, which, she said, for nine months had cameras set up around her home. Criss said agents determined the message was sent from London. They found no link to Durst.

The agent involved in the case did not return requests for comment.

Criss started carrying a gun. Her parents always reminded her to keep her doors locked.

“There was a period of time after that where I not only did carry a gun, I had guns and weapons hidden throughout my home,” she said. “What if he breaks in and the gun is at the other end of the house? People did think I was crazy.”

‘Highest level of weirdness’

She hid the butcher knives in her breadbox.

“If something happen, I’d know where they were,” she said. “I lived like that. I believe that somebody really bad came to my home to send a message to me.”

Criss’ obsession with the Durst case is such that she has been working on a book she wants to title “Descent into Madness.” The final chapter keeps changing.

“Every time you think you’ve reached the highest level of weirdness, we go again,” Criss said.

She knows more than she needs to know about Durst and his peculiarities: How he used to prepare for court sessions in the holding cell doing naked jumping jacks. How whenever he’s arrested, officers find guns, drugs and stacks of Metamucil. She learned the reason for the last item from listening to 32 hours of Durst’s recorded jailhouse phone calls.

“This man, his day, every day of his life, is defined as a success or not a success by how going and doing No. 2 went,” she said. “That was a part of the conversations with him… It had to happen at a certain time of day or his whole day was shot. The court staff used to joke that rearranging the court schedule was going to upset Bob’s schedule.”

A few years back, while Criss was campaigning for re-election and working the polls, a man approached her. Criss said it was a juror from the Durst trial, a man who had befriended the defendant, visited him in jail and dined with him at times. He must have seen a media report about the severed cat head.

“It seemed like he’s inappropriately happy to be asking me this question – ‘Hey, did anything ever happen about that cat head at your house?’” Criss recalled.

“I’m thinking to myself: You son of a bitch. I lied. I know the police weren’t doing anything about it. I said, ‘Oh yes, the police think they know who did. His demeanor changed and he couldn’t get away fast enough.”