Story highlights

Unlike the current commuter hub, New York's original Penn Station was a lavish Beaux Arts masterpiece

Guaira Falls was once the most powerful cataract in the world

The Porcelain Tower of Nanjing was considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Middle Ages

Ask a New Zealander what happened on June 10, 1886, and they’ll tell you the planet lost its “eighth wonder.”

The Pink and White Terraces of Lake Rotomahana were the world’s largest silica towers and the South Pacific’s biggest 19th-century attraction until a massive eruption at Mount Tarawera that momentous day blasted these natural wonders into oblivion.

Out of that same eruption, however, a new wonder of the world was born.

Waimangu Geyser roared into existence hurling black mud and sand some 1,500 feet (460 meters) into the sky, making it the most powerful geyser the world has ever seen.

This new attraction ignited a whirlwind of global interest in New Zealand’s volcanic North Island until it, too, vanished off the face of the earth in 1904 after a landslide changed the water table.

The Pink and White Terraces and Waimangu Geyser may be lost forever, but their impression on tourists of the time is well documented.

They are but two of many attractions of yesteryear that can now only be appreciated in the pages of a history book.

Here’s a look at 10 others:

1. Original Pennsylvania Station (New York)

The current Penn Station may be a charmless catacomb of labyrinthine low-ceiling hallways, but New York’s first Penn Station was a lavish masterpiece of the Beaux Arts style.

The original facility’s domed ceilings, soaring archways and handsome columns welcomed more than 100 million passengers each year during the station’s golden era in the mid-1940s. But by the end of the 1950s, the dawn of the Jet Age and the birth of the Interstate Highway System took a heavy toll on visitor numbers.

Plans for the new Penn Plaza and Madison Square Garden were announced in 1962, and a year later, the original Penn Station was knocked to the ground to make room for a smaller facility underground.

The demolition of Penn Station in 1963 was not without controversy. The New York Times questioned at the time how the city would “permit this monumental act of vandalism against one of the largest and finest landmarks of its age of Roman elegance.”

The whole affair is regularly cited as the catalyst for the modern historical preservation movement in the United States.

Within a decade of Penn Station’s demolition, Grand Central Terminal was protected under New York City’s new Landmarks Preservation Act.

2. Guaíra Falls (Paraguay, Brazil)

Guaira Falls was easily the most powerful cataract in the world in terms of total volume with 1,750,000 cubic feet of water passing through each second.

That’s more than double the flow of Niagara Falls and more than 12 times that of Victoria Falls. But good luck finding any trace of Guaira underneath the Itaipu Dam. More than three decades have now passed since one of the world’s greatest waterfalls was drowned to pave the way for a massive hydroelectric project.

This natural wonder, lost to the world in 1982, once lured hordes of local and international tourists to the Upper Parana River at the Brazil-Paraguay border.

It contained 18 falls in total with a drop of about 375 feet, and its deafening roar could be heard from up to 20 miles away.

3. Original Shakespeare’s Globe (London)

At least three Globe theaters have graced the shores of the River Thames over the past five centuries.

First there was the original Globe, built in 1599 by William Shakespeare’s playing company, the Lord Chamberlain’s Men.

A fire destroyed it during a performance of Henry VIII on June 29, 1613, but a second Globe Theatre opened on the same site exactly one year later.

It, too, closed in 1642 amid an outcry by Puritans who were opposed to theatrical performances.

The legacy of the first Globe Theatre and the iconic plays it debuted to the world lives on at the modern reconstruction, known as Shakespeare’s Globe, which opened its doors in 1997 approximately 750 feet from the original theater.

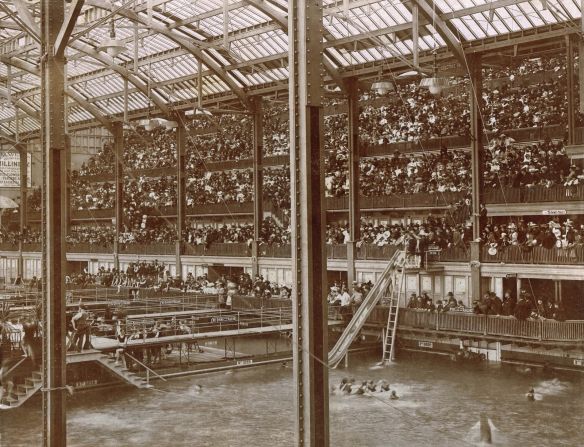

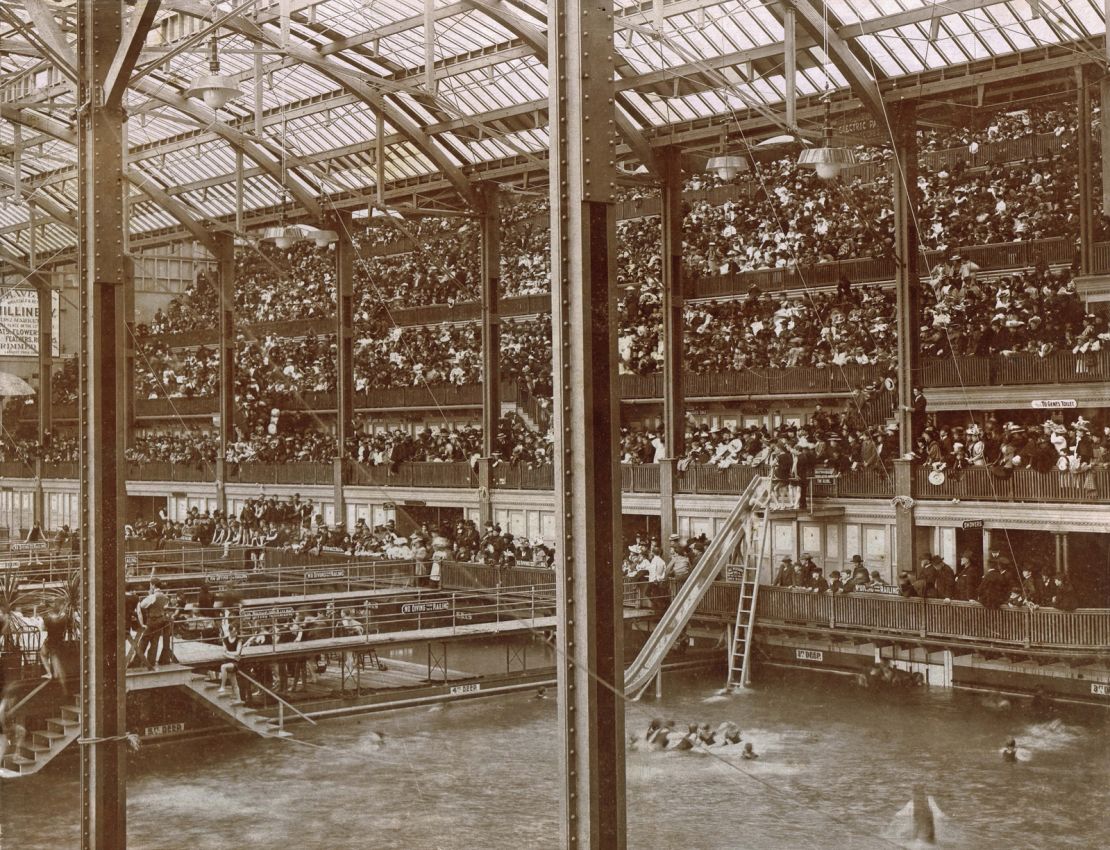

4. Sutro Baths (San Francisco)

When Sutro Baths first opened to the public in 1894, the three-acre complex housed a staggering seven pools (at varying temperatures) under a massive glass enclosure with springboards, high dives, slides and trapezes.

The facility could hold as many as 10,000 people at one time and also had several nonaquatic attractions such as a natural history museum with Egyptian mummies and a sculpture gallery with artifacts from Mexico and China.

The oceanfront property ensconced in the rocky San Francisco coast was considered a playground unlike any other the world had ever seen. Its Achilles’ heel, however, was an outsized price tag to match its ostentatious offerings.

With exceedingly high operational costs, the Baths were never a commercially successful business – even after owners turned the pools into ice skating rinks during the Great Depression.

The facility shut down for good in 1964 and was destroyed in a fire two years later. Its remains are now protected as part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area.

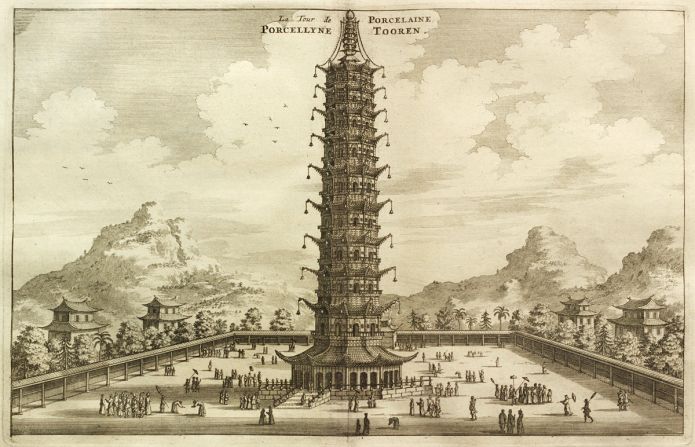

5. Porcelain Tower of Nanjing (China)

In an 1839 fairy tale called “The Garden of Paradise,” Hans Christian Andersen describes a teenager named East Wind who flies home from the East and tells his mother, “I came back from China, where I danced for a while around a tower of porcelain and rang all the bells.”

The Danish author’s fable may be a fantasy, but the tower of porcelain bricks was no figment of his vivid imagination.

Considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Middle Ages, the Porcelain Tower of Nanjing was built by the third emperor of the Ming Dynasty in the early 15th century and rose from a 97-foot octagonal base to a height of 260 feet.

This glossy nine-story pagoda soared above the south bank of the Yangtze River in Nanjing for more than four centuries before it was destroyed under the Taiping Rebellion of the 1850s.

Its rubble remained relatively untouched until 2010 when a businessman donated $156 million (the largest single donation in Chinese history) to rebuild the medieval icon.

6. The New York Hippodrome

The New York Hippodrome was billed as the largest theater in the world when it opened to the public in midtown Manhattan in 1905, featuring a 100-foot-by-200-foot stage and the capacity to seat up to 5,300 spectators.

This mammoth attraction lured the biggest acts of the day such as Harry Houdini and the “Jumbo” musical, but, like San Francisco’s Sutro Baths, it racked up a hefty upkeep bill.

Just 17 years after the Hippodrome opened, its owners refashioned the Moorish-style building into a vaudeville theater. Five years later it became a movie theater, then an opera house and finally a sports arena.

The doldrums of the Great Depression dealt one final blow to the facility and it was torn down in 1939 to make way for an office building and parking garage.

7. Chacaltaya Glacier (Bolivia)

The Chacaltaya Glacier lies 17,400 feet up in the Andes and was once one of Bolivia’s top tourist attractions, luring skiers the world over with the promise of tackling earth’s highest ski run.

Thanks to global warming, however, the 18,000-year-old wonder has been reduced to a few lumps of unskiable ice that no visitor would go out of their way to see.

In its prime it had the first rope tow in South America (built in 1939) and the highest ski lodge in the world, at an elevation greater than Everest Base Camp.

Chacaltaya was the closest ski area to the equator before it indefinitely closed in 2012. Known as the “bridge of ice” in the local Aymara language, Chacaltaya is but one of many glaciers currently retreating toward almost certain oblivion.

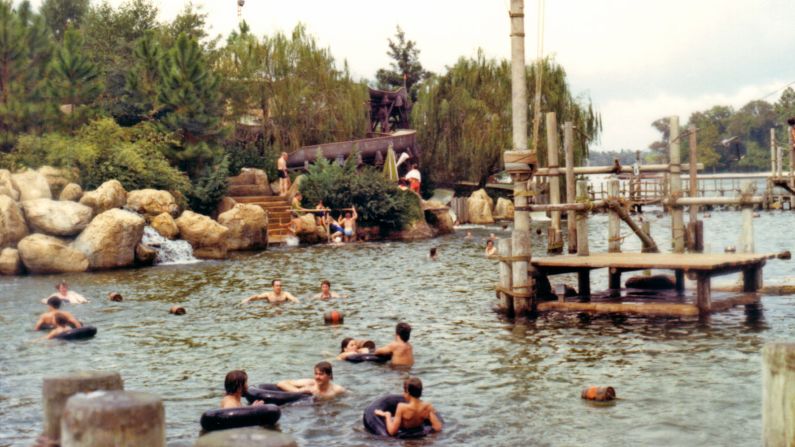

8. Disney’s River Country and Discovery Island (Florida)

Walt Disney World’s very first water park, River Country, is looking anything but jolly these days after lying abandoned on the shores of Bay Lake, Florida, for more than a decade.

The “old-fashioned swimming hole,” replete with swings, slides and whitewater rafting, closed for annual maintenance in 2001 never to open again.

Park officials cited declining business after 9/11 and the success of Walt Disney World’s two newer water parks, Typhoon Lagoon and Blizzard Beach, as reasons for their decision.

Bay Lake is also home to the only other Disney park to close permanently: Discovery Island.

This abandoned (but not demolished) zoological park was yet another 1970s-era attraction that lost favor with visitors and eventually closed to the public in 1999.

All animals were relocated to new homes at Disney’s Animal Kingdom, a much larger zoo that opened in 1998. A warning to any urban explorers out there: Disney employees still monitor both River Country and Discovery Island for trespassers.

9. Royal Opera House of Valletta (Malta)

Like the operas that brought its audiences to tears, the story of the Royal Opera House of Valletta is fittingly tragic.

Designed by Edward Middleton Barry in the 1860s, architect of the Royal Opera House in London’s Covent Garden, it was the crowning jewel of Malta’s capital city for just six years before a fire gutted the interior.

It was resurrected from the flames four years later, but tragedy struck again during World War II when the Royal Opera House received a direct hit from an aerial bomb. A few columns remain in place on the corner of Strada Reale, forming a backdrop for the open-air Royal Piazza Theatre, launched within the ruins of the Royal Opera House in 2013.

10. Jonah’s Tomb (Iraq)

Jonah’s Tomb in Mosul, Iraq, is the newest addition to this list and one of a series of attractions lost to war.

Militants with the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria, or ISIS, planted explosives in July 2014 around Mosul’s oldest mosque, which is traditionally held to be the burial place of Jonah the Prophet.

Jonah is a key figure in both Christianity and Islam who, according to Islamic and Judeo-Christian traditions, was swallowed by a whale.

His tomb was a popular place of pilgrimage and joins a growing list of holy sites deemed idolatrous under the puritanical strain of Islam practiced by ISIS.

Abandoned luxury hotels that you can’t afford to miss

Dreamland decay: The final moments of a forgotten theme park

Abandoned mines transformed into amazing tourist attractions

Mark Johanson is an American travel and culture writer based in Santiago, Chile.