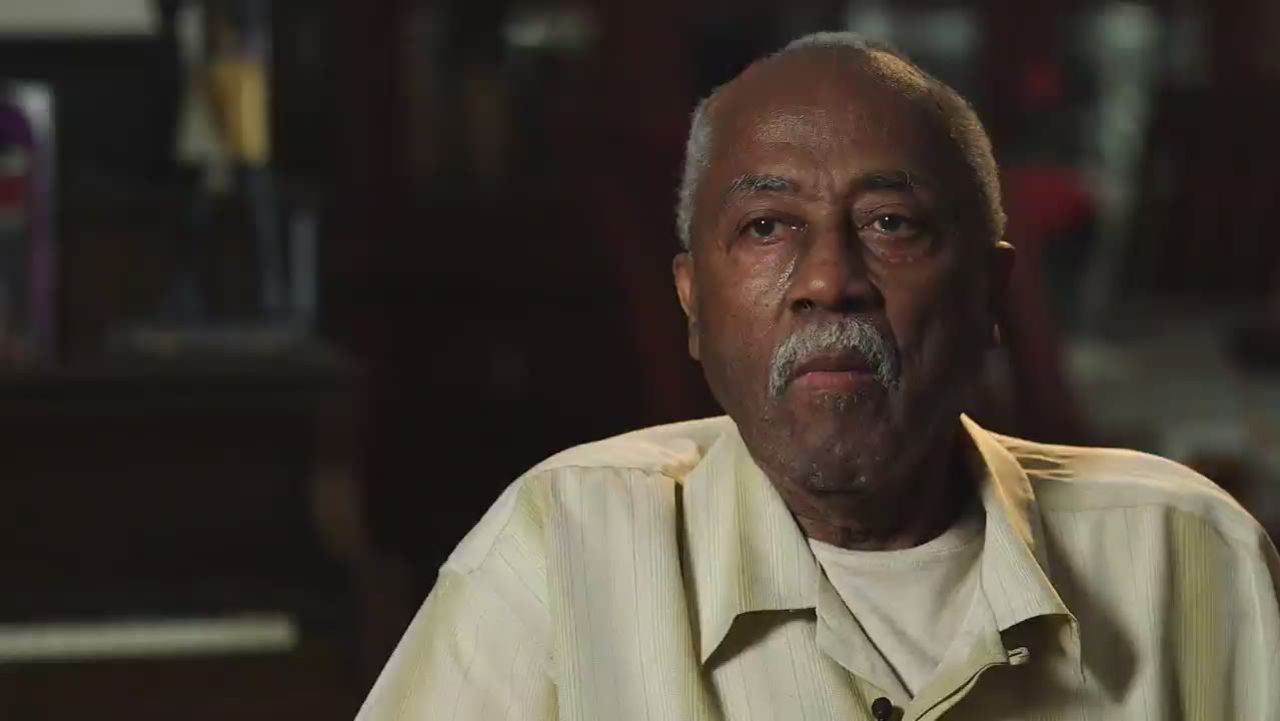

Editor’s Note: Zaheer Ali served as project manager of the Malcolm X Project at Columbia University, and as a lead researcher for Manning Marable’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention. He lectures on African American history. The views expressed are his own. Tune into a CNN special report, Witnessed, The Assassination of Malcolm X, tonight at 9p ET.

Story highlights

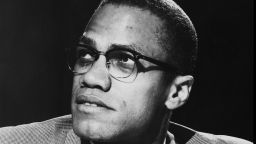

Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965

Zaheer Ali: Fifty years later, we still have more to learn from Malcolm X's life

When Malcolm X was assassinated on February 21, 1965, many Americans viewed his killing as simply the result of an ongoing feud between him and the Nation of Islam. He had publicly left the Nation of Islam in March 1964, and as the months wore on the animus between Malcolm’s camp and the Nation of Islam grew increasingly caustic, with bitter denunciations coming from both sides. A week before he was killed, Malcolm’s home – owned by the Nation of Islam, which was seeking to evict him – was firebombed, and Malcolm believed members of the Nation of Islam to be responsible. For investigators and commentators alike, then, his death was an open and shut case: Muslims did it.

Yet although three members of the Nation of Islam were tried and found guilty for the killing, two of them maintained their innocence and decades of research has since cast doubt on the outcome of the case. Tens of thousands of declassified pages documenting government surveillance, infiltration and disruption of black leaders and organizations – including Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam – suggest the conclusions drawn by law enforcement were self-serving. Furthermore, irregularities in how investigators and prosecutors handled the case reflect at best gross negligence, and at worst something more sinister.

At the time of his death, Time magazine remembered Malcolm X unsympathetically as “a pimp, a cocaine addict and a thief” and “an unashamed demagogue.” But for those who had been paying closer attention to him, Malcolm X was an uncompromising advocate for the urban poor and working-class black America. Instead of advocating integration, he called for self-determination; instead of nonviolence in the face of violent anti-black attacks, he called for self-defense. He reserved moral appeals for other people committed to social justice; the government, on the other hand, he understood in terms of organized power – to be challenged, disrupted and/or dismantled – and sought to leverage alliances with newly independent African states to challenge that power.

It was his challenge to the organized power of the state that appealed to growing numbers of African-Americans, and it was this challenge that also attracted a close following among federal, state and local law enforcement. Under Federal Bureau of Investigation Director J. Edgar Hoover’s watch, the FBI kept close tabs on Malcolm’s every move through the use of informants and agents. Even before Malcolm began attracting large audiences and widespread media coverage in the late 1950s and early ’60s, the FBI reported on his efforts to organize Nation of Islam mosques around the country. One organizing meeting in a private home in Boston in 1954 had maybe a dozen or so people present; one of them reported to the FBI.

After Malcolm left the Nation of Islam in March 1964, agents pondered the prospect of a depoliticized more religious Malcolm, but still perceived him as a threat. On June 5, 1964, Hoover sent a telegram to the FBI’s New York office that simply and plainly instructed, “Do something about Malcolm X enough of this black violence in NY.” One wonders, what that “something” was.

In New York, the FBI’s actions were complemented by, if not coordinated with, the New York Police Department’s Bureau of Special Services, which regularly logged license plates of cars parked outside mosques, organizational meetings, business and homes. The actions of the police on the day of Malcolm’s assassination are particularly noteworthy. Normally up to two dozen police were assigned at Malcolm X’s rallies, but on February 21, just a week after his home had been firebombed, not one officer was stationed at the entrance to the Audubon ballroom where the meeting took place. And while two uniformed officers were inside the building, they remained in a smaller room, at a distance from the main event area.

The lack of a police presence was unusual and was compounded by internal compromises on the part of Malcolm’s own security staff, which included at least one Bureau of Special Services agent who had infiltrated his organization. Reportedly at Malcolm’s request, his security had abandoned the search procedure that had been customary at both Nation of Islam and Muslim Mosque/Organization of Afro-American Unity meetings. Without the search procedure, his armed assassins were able to enter the ballroom undetected. When the assassins stood up to shoot Malcolm, his security guards stationed at the front of the stage moved not to secure him, but to clear out of the way.

These anomalies, in and of themselves, could have been inconsequential. But combined, even if just by coincidence, they proved to be deadly, and allowed for one of the most prophetic revolutionary voices of the 20th century to be silenced. The investigation that followed was just as careless. The crime scene was not secured for extensive forensic analysis – instead, it was cleaned up to allow for a scheduled dance to take place that afternoon, with bullet holes still in the wall!

For activists, of course, Malcolm X’s death took on greater significance than law enforcement publicly expressed. Congress of Racial Equality Chairman James Farmer was among the first to suggest that Malcolm’s murder was more than just an act of sectarian violence between two rival black organizations. “I believe this was a political killing,” he asserted, in response to Malcolm’s growing national profile within the civil rights movement. He called for a federal inquiry – unbeknownst to Farmer, an ironic request given the level of covert federal oversight that was already in place.

Slowly, Farmer’s doubts gained considerable traction. Author and journalist Louis Lomax, who had covered Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam on several occasions, put Malcolm X’s assassination in context with Martin Luther King Jr.’s in “To Kill a Black Man” (1968). More than four decades ago, activist George Breitman was among the first to challenge the police version of who was responsible for Malcolm X’s death. More recently, the work done at Columbia University’s Malcolm X Project, culminating in Manning Marable’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention,” echoed these doubts and put at the forefront these unanswered questions about Malcolm X’s murder.

These questions deserve answers. They call upon us to revisit not just the political significance of Malcolm X’s life, but the implications of his murder. Our government especially deserves scrutiny for its covert information gathering, disinformation campaigns, and even violence waged against its own citizens. Fifty years later, we still have more to learn from Malcolm X’s life, and his death, and our government’s actions toward him.