Editor’s note: Donna Brazile, a CNN contributor and a Democratic strategist, is vice chairwoman for voter registration and participation at the Democratic National Committee. A nationally syndicated columnist, she is an adjunct professor at Georgetown University and author of “Cooking With Grease: Stirring the Pots in America.” The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of the author.

Story highlights

Donna Brazile: "Selma" has stirred a controversy over its historical accuracy

She says critics miss the point; movie isn't a documentary, but it has a powerful message

“Selma,” the new feature film about the civil rights struggle, is igniting a struggle of its own over who deserves credit – or blame – in the events of 50 years ago that are depicted in the movie.

Some have taken issue with the portrayal of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Former LBJ administration officials are crying foul, saying that the portrayal of Johnson distorts and tarnishes the record of a man who had become an ally in the fight, committed to the goal and focused on how best to achieve the goal – given the role of Congress and outside forces.

Johnson’s legacy has long been overshadowed by the quagmire of the Vietnam War, and his supporters hope to burnish the image of his presidency by highlighting his efforts in passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It’s the struggle for the latter that is portrayed in “Selma.” But the movie shows Johnson as worried that the fight for voting rights will endanger the chances of success for other items on his Great Society agenda, and he pressures the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. to wait.

When King is adamant, the film implies that Johnson even allows J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI to pressure the civil rights leader by sending his wife, Coretta Scott King, supposed audio recordings of King having sex with another woman.

Even before the movie was in wide release, LBJ Presidential Library Director Mark Updegrove, writing in Politico, said, ” ‘Selma’s’ obstructionist LBJ is devoid of any palpable conviction on voting rights. Vainglorious and power hungry, he unleashes his zealous pit bull, FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover, on King.” Updegrove claims the movie “flies in the face of history.”

Writing in The Washington Post, Joseph A. Califano Jr., one of Johnson’s top aides, accuses the movie of using “dramatic, trumped-up license.” “In fact,” he adds, “Selma was LBJ’s idea, he considered the Voting Rights Act his greatest legislative achievement, he viewed King as an essential partner in getting it enacted – and he didn’t use the FBI to disparage him.”

“Selma” director Ava DuVernay responded to the criticism on Twitter, posting that the “Notion that Selma was LBJ’s idea is jaw dropping and offensive to SNCC, SCLC and black citizens who made it so” (in a reference to the civil rights organizations Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference.)

In a subsequent tweet she told people not to take anyone’s word for it, but that “Bottom line is folks should interrogate history.” Of course, once you start interrogating history, you rarely get simple answers. The actions and motivations of real people in real historical events are complicated and ambiguous.

Once you take those real people and events and put them into a movie – even one that strives for historic accuracy – you add even more complications and ambiguity. It’s not possible to re-create, or even agree on, exactly what happened in the past. If those who forget the past are condemned to relive it, it seems that those who re-enact the past are condemned to revise it.

Julian Zelizer: The real story behind ‘Selma’

Johnson may be portrayed as flawed, but he’s certainly not the villain of the movie – Alabama in 1965 had villains aplenty. Johnson is shown as a man with ambitious goals and strong-arm methods, and a cold pragmatism when it came to deciding what could be done when.

It could be argued that – like King – LBJ is keeping his “eyes on the prize,” and he’s not concerned if he tramples a few toes while he’s transfixed with the goal. He’s a politician, not a saint, and he concentrates more on what’s most doable than what’s most noble.

He’s not above using the N-word in a private conversation with Alabama Gov. George Wallace, but he uses it while trying to get Wallace to offer protection to King’s marchers.

Johnson may ultimately be on the side of the angels, but he’s willing to use devilry to achieve his goals. Like any great movie character – or real human being – he is complicated and multifaceted. In one of the scenes that has caused the most controversy, when King is urging a reluctant LBJ at the White House, they do it in front of a portrait of George Washington – a subtle reminder of how long we have been discussing race in America.

If the LBJ of “Selma” is shown as imperfect, he’s not alone. The leaders in the many factions of the civil rights movement are shown as fractious, jealous of their prerogatives and at times petty. Even King’s shortcomings are on display, as it’s implied that the accusations of infidelities against him may be true.

At one point, King, doubtful about his next move, is shown calling up gospel singer Mahalia Jackson for inspiration. Jackson was a strong supporter of the movement. In fact, King had called her to come down to Alabama during the Montgomery bus boycott. The very fact that we are dealing with real human beings and not abstractions is what makes their struggle seem even more impressive.

Andrew Young: The miracle of Selma

“Selma” is a movie, not a documentary. It neither claims nor tries to give a 100% accurate telling of the story – or the events that led to this seminal moment in the civil rights struggles in the 1960s.

Director DuVernay was even forced to rewrite the speeches of King used in the movie as loose paraphrases because his estate licensed his speeches to another studio for a different movie. As in any work of art, in this movie choices have to be made in what to portray and in how to portray it.

The goal of art is to arrive at fundamental truths that do not rely on the details of incidents being portrayed for their relevance. And if a work of art is successful in that, it will illuminate the events in ways that transcend the time and place being portrayed, and transcend the time and place of the work of art itself.

One of the choices made in the making of “Selma” is to keep the focus on the marchers and the people who were putting their lives and safety on the line. Part of that focus may be because the director is an African-American woman. She may be trying to avoid the often annoying tendency of movies dealing with important events in African-American history to concentrate on white protagonists.

Films such as “Glory” and “Mississippi Burning” sometimes treat the African-Americans whose stories are being told like they are passive agents in a narrative that depends on a white hero riding in to save the day, presumably on a white horse.

The portrayals in “Selma” shouldn’t be seen as a dismissal of Johnson’s contributions to the fight civil rights, but as an affirmation of the struggles of the people who were in the middle of that fight, and who had vowed not to fight back with violence. It’s a case of keeping your eyes not only on the prize, but on the proper protagonists.

Something else that may be at work here is that we are currently embroiled in another clash in the long, long struggle for equal rights with the ongoing protests over treatment of African-Americans under the justice system.

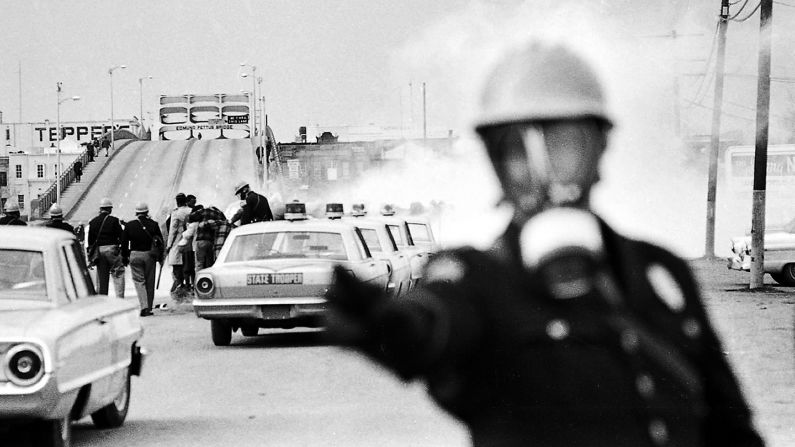

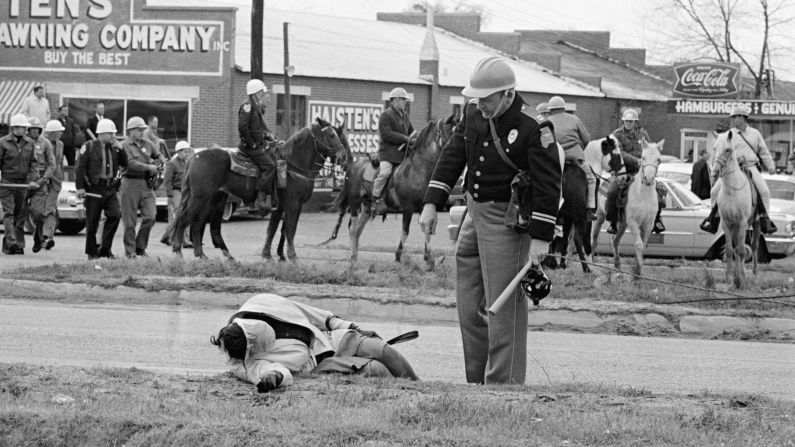

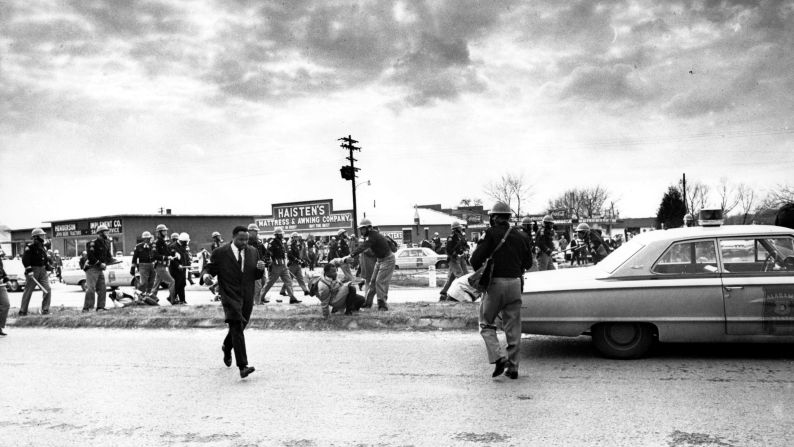

It’s impossible to see the images of peaceful protesters being brutally attacked on the bridge in “Selma” without being reminded of the images of Eric Garner being dragged to the ground in a chokehold. But both the protests today and the events depicted in the movie show that we need commitment and cooperation from good-hearted people of all races and creeds.

At the end of the movie, viewers are updated on the subsequent fates of the people portrayed in the film, many of which we know all too well. I just wish that they had given an update on the fate of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. That postscript would have to say something like “The Voting Rights Act of 1965 led a successful and productive life until 2013 when key provisions in it were struck down by the Supreme Court. It is currently on life support.” That would alert viewers to the need to continue the fight.

Is “Selma” a note-perfect recreation of everything that happened regarding the struggles in passing the Voting Rights Act of 1965? No, because it’s not meant to be.

It’s meant to be something much more, and at that it succeeds. After watching the movie “Selma,” I can’t say I was at Selma. And I can’t say I know what it must have felt like to be there. But I experienced a visceral reaction to a depiction of those events that inspired me, that motivated me … and that made me want to march on as we continue the struggle for universal suffrage.

Read CNNOpinion’s new Flipboard magazine