Vital Signs is a monthly program bringing viewers health stories from around the world.

Story highlights

In 2009, HIV vaccine trial in Thailand to offered glimmers of hope for a future vaccine

A modified form of the vaccine is to be tested in South Africa from January

Broadly neutralizing antibodies could offer another avenue against the range of HIV viruses

Protective levels of 50% would have an impact on public health

“It only takes one virus to get through for a person to be infected,” explained Dr. John Mascola. This is true of any viral infection, but in this instance, Mascola is referring to HIV and his ongoing efforts to develop a vaccine against the virus. “It’s been so difficult to make an HIV/AIDS vaccine.”

Those were the words of many working in HIV vaccine development until the results of a 2009 trial in Thailand surprised everyone. “The field is energized,” said Mascola, director of the Vaccine Research Center at the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, describing the change in atmosphere in the vaccine community.

The trial included over 16,000 volunteers and was the largest clinical trial ever conducted for a vaccine against HIV. It was also the first to show any protection at all against infection.

Two previously developed vaccines, known as ALVAC-HIV and AIDSVAX, were used in combination, with the first priming an immune response against HIV and the second used as a booster once the immunity waned. The duo reduced the risk of contracting HIV by 31.2% – a modest reduction, but it was a start.

To date, only four vaccines have made it as far as testing for efficacy to identify their levels of protection against HIV. Only this one showed any protection.

“That trial was pivotal,” Mascola said. “Prior to that, it wasn’t known whether a vaccine could be possible.”

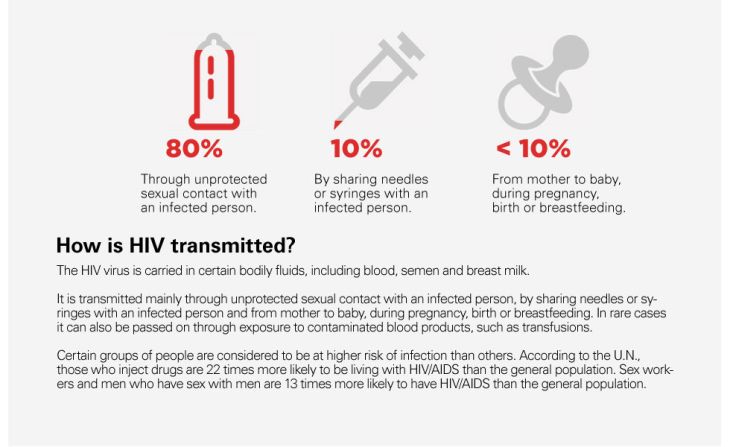

In recent years, there have been parallel findings of an equally pivotal nature in the field of HIV prevention, including the discovery that people regularly taking their antiretroviral treatment reduce their chances of spreading HIV by 96% and that men who are circumcised reduce their risk of becoming infected heterosexually by approximately 60%.

Both improved access to antiretrovirals and campaigns to increase male circumcision in high-risk populations have taken place since the discoveries, and although numbers of new infections are falling, they’re not falling fast enough.

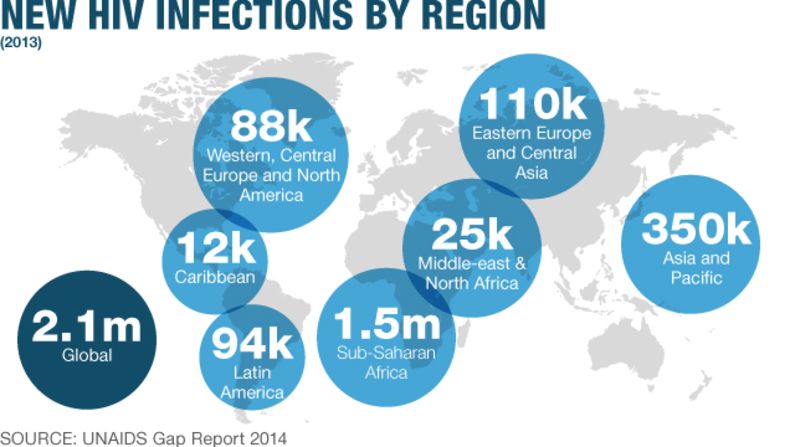

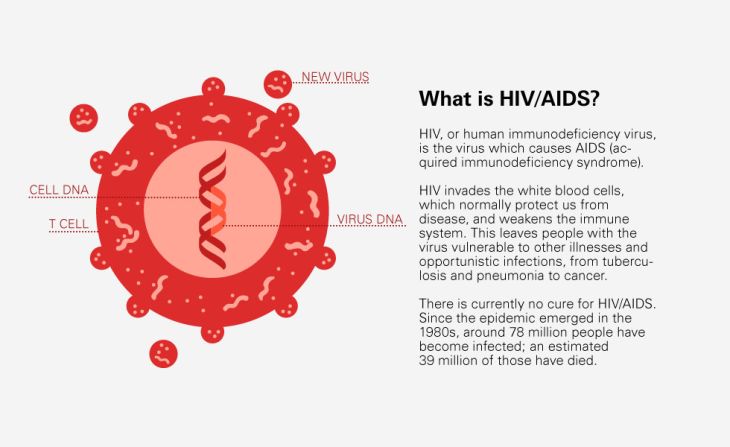

In 2013, there were 35 million people estimated to be living with HIV globally. There were still 2.1 million new infections in 2013, and for every person who began treatment for HIV last year, 1.3 people were newly infected with the lifelong virus, according to UNAIDS. A vaccine remains essential to control the epidemic.

A complex beast

Scientists like Mascola have dedicated their careers to finding a vaccine, and their road has been tough due to the inherently complicated nature of the virus, its aptitude for mutating and changing constantly to evade immune attack, and its ability attack the very immune cells that should block it.

There are nine subtypes of HIV circulating in different populations around the world, according to the World Health Organization, and once inside the body, the virus can change continuously.

“Within an individual, you have millions of variants,” explained Dr. Wayne Koff, chief scientific officer for the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative.

HIV invades the body by attaching to, and killing, CD4 cells in the immune system. These cells are needed to send signals for other cells to generate antibodies against viruses such as HIV, and destroying those enables HIV to cause chronic lifelong infections in those affected.

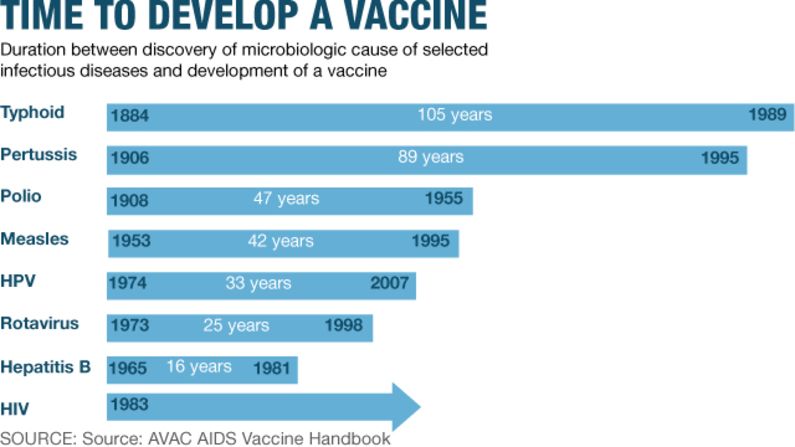

Measles, polio, tetanus, whooping cough – to name a few – all have vaccines readily available to protect from their potentially fatal infections. But their biology is seemingly simple in comparison with HIV.

“For the older ones, you identify the virus, either inactivate it or weaken it, and inject it,” Koff said. “You trick the body into thinking it is infected with the actual virus, and when you’re exposed, you mount a robust immune response.”

This is the premise of all vaccines, but the changeability of HIV means the target is constantly changing. A new route is needed, and the true biology of the virus needs to be understood. “In the case of HIV, the old empirical approach isn’t going to work,” Koff said.

Scientists have identified conserved regions of the virus that don’t change as readily, making them prime targets for attack by antibodies. When the success of the Thai trial was studied deep down at the molecular level, the protection seemed to come down to attacking some of these conserved regions. Now it’s time to step it up.

In January, the mild success in Thailand will be applied in South Africa, where over 19% of the adult population is living with HIV. The country is second only to bordering Swaziland for having the highest rates of HIV in the world.

“The Thai vaccine was made for strains (of HIV) circulating in Thailand,” said Dr. Larry Corey, principal investigator for the HIV Vaccine Trials Network, which is leading the next trial in South Africa. The strain, or subtype, in this case was subtype B. “For South Africa, we’ve formed a strain with common features to (that) circulating in the population.” This region of the world has subtype C.

An additional component, known as an adjuvant, is being added to the mix to stimulate a stronger and hopefully longer-lasting level of immunity. “We know durability in the Thai trial waned,” Corey said. If safety trials go well in 2015, larger trials for the protective effect will take place the following year. An ideal vaccine would provide lifelong protection, or at least for a decade, as with the yellow fever vaccine.

A broad attack

The excitement now reinvigorating researchers stems not only from a modestly successful trial but from recent successes in the lab and even from HIV patients themselves.

Some people with HIV naturally produce antibodies that are effective in attacking the HIV virus in many of its forms. Given the great variability of HIV, any means of attacking these conserved parts of the virus will be treasured and the new found gold comes in the form of these antibodies – known as “broadly neutralizing antibodies.” Scientists including Koff set out to identify these antibodies and discover whether they bind to the outer coat of the virus.

The outer envelope, or protein coat, of HIV is what the virus uses to attach to, and enter, cells inside the body. These same coat proteins are what vaccine developers would like our antibodies to attack, in order to prevent the virus from entering our cells. “Broadly neutralizing antibodies” could hold the key because, as their name suggests, they have a broad remit and can attack many subtypes of HIV. “We will have found the Achilles heel of HIV,” Koff said.

Out of 1,800 people infected with HIV, Koff and his team found that 10% formed any of these antibodies and just 1% had extremely broad and potent antibodies against HIV. “We called them the elite neutralizers,” he said of the latter group. The problem, however, is that these antibodies form too late, when people are already infected. In fact, they usually only form a while after infection. The goal for vaccine teams is to get the body making these ahead of infection.

“We want the antibodies in advance of exposure to HIV,” explained Koff. The way to do this goes back to basics: tricking the body into thinking it is infected.

“We can start to make vaccines that are very close mimics of the virus itself,” Mascola said.

Teams at his research center have gained detailed insight into the structure of HIV in recent years, particularly the outer coat, where all the action takes place. Synthesizing just the outer coat of a virus in the lab and injecting this into humans as a vaccine could “cause enough of an immune response against a range of types of HIV,” Mascola said.

The vaccine would not contain the virus itself, or any of its genetic material, meaning those receiving it have no risk of contracting HIV. But for now, this new area remains just that: new. “We need results in humans,” Mascola said.

Rounds of development, safety testing and then formal testing in high-risk populations are needed, but if it goes well, “in 10 years, there could be a first-generation vaccine.” If improved protection is seen in South Africa, a first-generation vaccine could be with us sooner.

Making an Impact

When creating vaccines, the desired level of protection is usually 80% to 90%. But the high burden of HIV and potentially beneficial impact of lower levels of protection warrant licensing at a lower percentage.

“Over 50% is worth licensing from a public health perspective,” Koff said, meaning that despite less shielding from any contact with the HIV virus, even a partially effective vaccine would save many lives over time.

The next generations will incorporate further advancements, such as inducing neutralizing antibodies, to try to increase protection up to the 80% or 90% desired.

“That’s the history of vaccine research; you develop it over time,” Corey said. He has worked in the field for over 25 years and has felt the struggle. “I didn’t think it would be this long or this hard … but it’s been interesting,” he ponders.

But there is light at the end of tunnel. Just.

“There has been no virus controlled without a vaccine,” he concluded when explaining why, despite antiretrovirals, circumcision and increased awareness, the need for a one-off intervention like a vaccine remains strong.

“Most people that transmit it don’t even know they have it,” he said. “To get that epidemic, to say you’ve controlled it, requires vaccination.”